As mentioned in our Gardening With Chickens post, small-scale poultry rearing in the United States has become very popular in recent years. Owning poultry comes with numerous responsibilities, including the daily care and welfare of our flocks. The most important task however is ensuring that our flocks are healthy, and that we’re doing what we can to protect them from disease.

Many small flock owners probably don’t think very much about disease and illness in their flocks until a bird becomes sick, but it’s important to always be watchful for early signs of disease in your birds.

Disease Prevention

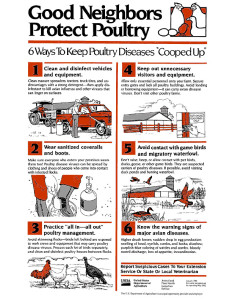

Basic things you can do to protect your flocks are to:

- Disinfect shoes, clothing, hands, equipment, and vehicles, particularly after visiting other poultry farms or fairs

- Buy birds only from reputable sources

- Keep new birds separated from the rest of your flock for at least 30 days

- Separate young and old birds, birds of different species, and birds from different sources

- Keep records of all purchases, sales and shipments

Monitoring for Signs of Illness:

At Curbstone Valley our policy is that every bird on the farm is observed daily, at least once, although our birds are typically monitored multiple times each day.

As prey species, chickens and turkeys are often adept at masking signs of illness until they are very ill. Vigilant observation is the best tool for catching subtle signs of potential disease. Some more subtle signs of illness include:

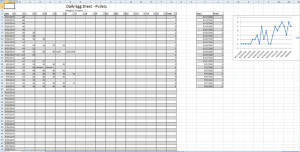

Sudden declines in egg laying

A rapid decline in egg production, not attributable to molt, can be a significant clue that the flock may be ill. We monitor egg production closely using egg-laying worksheets. Every egg collected each day is weighed, and logged. Thin-shelled, broken, or shell-less eggs are also tracked. Daily and weekly averages are calculated so that any significant changes in production are easily noticed.

Although shifts in egg production can indicate a flock health problem, it is important to recognize that egg-production in poultry is not static.

Hens experience natural variations in egg-laying, but sudden changes in egg-production may be suggestive of something more sinister within the flock

Periods of excessive heat may stress birds, causing them to briefly decrease egg-production, and shortening days from late summer through mid-winter can cause birds to exhibit a seasonal decline.

Individual birds separated from the flock

Behavioral changes in chickens and turkeys can be very subtle, and this is why it is imperative to observe your birds daily. This way small shifts in behavior are more likely to be caught. An individual bird that is separated from the flock for extended periods, or refusing to roost at night, may feel unwell. Chickens can often sense when a flock-mate becomes ill. If members of a flock are suddenly picking on a flock-mate this may indicate illness in the bird being targeted by other members of the flock. Not all maladies in poultry are infectious, so again, it’s important to evaluate any problem-birds relative to the health of the remainder of the flock.

Decrease in feed and/or water consumption

Changes in feed and or water intake by an individual may not be readily apparent. However, a sudden decline in feed intake flock-wide, especially for birds that are not supplementing their diets on range, is a cause for concern and warrants further investigation.

Sudden changes in comb and wattle color

Comb and wattle color is an excellent indication in egg-laying hens as to whether they are in lay or not. During periods of molt, or prior to egg-laying in young pullets, the comb and wattles tend to be more pale pink in coloration. Actively laying hens usually exhibit bright red combs and wattles. Sudden shifts in coloration from one day to the next however may be a clue that a bird isn’t feeling well, or is experiencing environmental stress.

Blue, purple, grey or excessively pale coloration may indicate significant illness or stress in that individual.

'Roo's' comb usually stood upright, but during an acute episode of egg-binding, her comb collapsed, and was an early indication that something was wrong

Comb position in some breeds can also be an indicator of health, especially in single-combed breeds. An individual that has a bright-red comb, standing tall and upright on Friday, that suddenly has a pale or purple comb, that has flopped over on Saturday, is an obvious sign that something is amiss with that individual.

Caring for Sick Birds:

How you choose to manage your birds when an individual becomes ill, may be different than if your entire flock becomes sick. An individual bird that is ill should be pulled from the flock and housed separately so it can be observed more closely, and not be picked on by flock-mates while it is weak. A portable poultry tractor or ark, or even a large dog kennel bedded with deep straw, can be used to isolate a sick bird.

Individually housing an ill bird affords the opportunity to more closely monitor feed and water intake, and the volume and quality of outputs. Detecting constipation or diarrhea in a bird housed with the flock is difficult, but separated from the flock, products of elimination are more easily evaluated for consistency, volume and color, all of which provide important clues as to the health of that individual. Depending on the value of the bird, you may elect to seek Veterinary care for an ill bird, or choose to cull the individual if the condition of the animal doesn’t improve.

Managing a Sick Flock

If your flock becomes ill, or if you suspect an individual bird may have a potentially infectious disease, it’s important to err on the side of caution. Infectious diseases may be viral, bacterial, or parasitic in origin, or a combination thereof. Any flock health concerns need to be addressed promptly, as these may be caused by infectious diseases that can spread rapidly, and kill your flock, or infect neighboring flocks. Residual infectious diseases that persist in the environment can also affect your replacement flocks.

The are a number of potentially infectious diseases of fowl, but currently the two of most significant concern in the United States are:

Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI)

Exotic Newcastle disease (END)

As poultry owners, it is our responsibility to be aware of signs of infectious disease in our flocks, for the welfare of existing and future flocks. In addition to the signs listed above, other signs to be watchful for include, but are not limited to:

- Coughing

- Sneezing

- Nasal or ocular discharge

- Facial swelling

- Gasping for air

- Watery and green diarrhea

- Drops in egg production, or increases in soft, thin-shelled, or misshapen eggs

- Tremors, drooping wings, paresis, paralysis, circling, twisting of the head and neck (END)

- Changes in comb, wattle, and leg color (HPAI)

- Sudden increases in flock mortality

Signs of infectious disease in a flock should be reported to your local, or state Veterinarian, or extension office immediately.

Although rare, all poultry owners should at least familiarize themselves with signs of END and HPAI. We’ll review both of these diseases, in addition to other common diseases of poultry, in some of our future Fowl Friday posts.

But I only have a few birds, why should I report a couple of sick birds to my Vet?

Because END and HPAI are spread from wild birds to backyard and small free-range flocks more easily than to large commercial flocks that are raised indoors. As such, disease outbreaks are more likely to show up in small flocks first.

To illustrate this, the last outbreak of Exotic Newcastle Disease in California in 2002 began in a half dozen small backyard flocks of chickens in southern California. Initially the disease was confined to small privately owned flocks, but by early 2003 the virus had spread, likely through poultry exhibitions, sale of birds, illegal cock-fighting operations, and wild birds who can also carry the disease. Eventually the disease spread and affected commercial poultry producers, resulting in more than 4 million birds being destroyed, and almost 400 million dollars of lost revenue in the State.

Containment of such disease outbreaks is dependent on early detection and quarantine. Although the majority of eggs and meat produced for consumption are still through large corporate operations, with the increasing popularity of organic free-range eggs, and organic free-range meats, many small farms now depend, at least in part, on revenue generated from their flocks. Backyard pet birds are also not immune from disease outbreaks. Both small scale free-range operations, and backyard flocks, are potentially at higher risk for HPAI and END, as those birds aren’t isolated from wild birds that may be carrying disease, compared to most large-scale commercial flocks that are raised indoors. This makes containment of outbreaks all the more challenging. Currently poultry owners in the state of Wisconsin are on alert after a virulent strain of Newcastle disease was detected in wild birds in August of this year.

As much as we hope an infectious avian disease outbreak will never happen again, it’s fair to assume that there will be another outbreak of virulent, and widespread, avian disease in California, the question is simply when. At which time any poultry owners, from small back-yard flocks, to large scale operations may be affected. Free-ranging operations, and back yard flocks will be at highest risk due to the potential for direct contact with wild birds. As the outbreak in 2002 shows, it is imperative that sick birds are reported immediately if an outbreak is to be effectively controlled, even if you only have a few chickens. We aren’t currently producing eggs for sale, but still recognize the importance, both to other flocks, and to the State’s economy, of reporting potentially infectious disease.

Ideally, we’d never see another outbreak, but in the meantime, it’s important that we do what we can to keep our fowl safe. If you have birds, from poultry to parrots, note that November 1-7, 2010 is Bird Health Awareness Week.

The following video from the USDA provides a good general overview of what you can do to help keep your birds safe.

For more on what you can do to protect your fowl, visit the US Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) ‘Biosecurity for Birds’ website.

Great post! Thanks for the write up.

You have such great information! I had no idea of all of the things that need to be observed on chickens.

Dear Clare, It is so important that when people take on any animals they are fully aware of how to look after them, since animals are so dependent upon their human owners for their basic needs and welfare. This is a very comprehensive posting which should be used as a warning message for anyone proposing to keep chicken without the full knowledge of how to keep them healthy.

How is Frodo?

No worries, Frodo is fine, and finally realizing he’s a rooster! We’ll have an update on him, and his new house, very soon!

Wow, that’s a lot of great information! Does make me glad I only have to worry about too much water or not enough; plants are easy.

Clare, you provide such invaluable information on all aspects of raising poultry – the good, the bad, and the ugly. It’s always good to know what you’re getting into, especially for newbies like myself. What breed would you recommend for the novice, and do you generally buy chicks or eggs for the incubator? I really like the Buff Orpingtons and have read that they are decent egg layers with nice temperaments.

We usually start with 1-2 day old chicks. You can get hatching eggs, but I wouldn’t recommend that for the novice, as it’s not as straightforward as it seems, and it requires additional expensive equipment.

Of the breeds we’ve had thus far, my two favorites are the Buff Orpingtons, and Black Australorps. Both are very good egg layers, with very placid dispositions overall. They’re also both readily available from hatcheries and breeders. The breed I wouldn’t go out of my way to obtain, of those we currently have, would be the Golden Laced Wyandottes. Their personality doesn’t fit with the rest of flock, being significantly more aggressive than any of the other breeds we currently have.

What an important and helpful post Clare! Brava!!

That wasn’t a blog post, that was a scholarly article. Thanks for the great info and putting in such effort to share best practices. Most appreciated.

Clare I never realised that you weighed and kept records of eggs – wow thats alot of work as you’ve got quite alot of chickens.

This weekend I noticed a sick wild bird in my garden – and reported it. For the next month I am not feeding the birds incase it spreads as this wild bird contaminated my feeders and bird bath with its saliva.

Clare you are a dedicated poultry-woman! Your birds are so lucky to have you caring for them~Looking forward to update on Frodo and just to share~I had my first farm fresh eggs in decades. Boy can you tell a difference. Worth the extra cost from the Farmer’s Market! gail

This is awesome information. Thank you for posting it.

Beautiful birds, Clare, blessed to be under your caring wings. If I was a chicken, I would love to live my life with you 🙂

What useful information and good to know you take such careful measures at your farm! Your birds look healthy and happy.

This is so interesting. I have had such fun observing my sister’s chickens and enjoying their eggs. But, you post shows that you do have to take raising chickens seriously. Your chicken posts are my favorites 🙂

I keep chuckling to myself because I know that if I keep reading your blog I see chickens in my future. Not really, well…, 🙂 but I do love chickens and really enjoy your posts.