Beekeepers in this area have been telling us for some time that this has been a very bad year for Varroa mites. By late summer we knew that one of our hives had an escalating Varroa mite problem, which we outlined in our last post. The other three hives in the apiary still had low mite counts, but knowing the burden was high in one, we elected to treat all four hives in mid-August.

As it was still technically summer when we started treatment, we elected to use a Thymol based product.

After two weeks of treatment, just for our own interest, we went ahead and did a mid-treatment mite count. As expected, the mite population had not appreciably decreased (for an explanation as to why, see our previous post). In fact, in three of four hives the mite populations had actually increased slightly.

At that time we weren’t sure if the increasing mite counts in those hives was due to increased mite drop, directly as a result of treatment (accelerating the drop in mites), or if the mites were managing to gain population despite treatment.

General Inspection Findings

This weekend we went back into the hives, primarily to check on food reserves, and remove the remaining drone frames, and then perform our end of treatment mite count, hoping to see a decline in mite population.

For all the hives, except Rosemary, the Thymomite pads were more or less where we left them. We did note two things of significance though. The first is that the Rosemary hive, for reasons known only to the bees, insisted that the Thymomite must be removed from the hive.

At the start of this inspection we found one partially broken down pad on the ground in the apiary. We suspected this was from the Rosemary hive as we’d seen a pad at the hive entrance a few days before. Indeed, the inspection showed that only the Rosemary hive was missing most of their Thymol strips. I remember spitting out cough syrup as a child, so I can hardly blame them.

We thoroughly inspected the Salvia hive first, and as we were wrapping up that inspection, we noticed that Rosemary was wrestling yet another Thymol strip out of the hive.

It was remarkable to watch the bees attempt to pull this massive strip up and over the robbing the screen (left), but they gave up and dropped it (right), so we removed it

We watched as bees at the entrance, with apparent herculean strength, struggled to carry the Thymol pad OVER the robbing screen! These bees clearly wanted this OUT of their hive! As such, we wondered just how effective this treatment would prove to be for that colony.

The other point of note is that our feral colonies, Salvia, and Lavender, both heavily propolised around the Thymol pads on the top bars.

Rather than drag the Thymol pads out of the hive like Rosemary, they just tried to wall it off. Quite literally.

However, neither of our Italian bee colonies, Rosemary and Chamomile, put any propolis around the pads. You can see propolis around the edge of the frames here in the Rosemary hive, but note there’s NONE around the Thymol pad at all.

Apparently our Feral bees like to produce a lot more propolis than the Italians.

Also of note, despite not taking any honey this year, all the hives were low on honey and pollen stores.

Most notably, all the hives were showing significantly more spotty brood patterns. Whether that is a result of treatment, or mite levels, isn’t clear, but we suspect it’s likely both.

The brood nests in all the hives have a spotty laying pattern, with various ages of larva at any given location

Treatment Results

The Thymol treatments appeared to be somewhat disruptive to the colonies, but what about the treatment effectiveness over the last month? Has it knocked back the Varroa counts as much as we hoped? This is where things get interesting.

The short answer is that at first glance the treatment seems to have failed. However, I suggest you read on, as the answer isn’t really that simple.

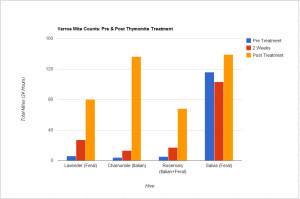

The chart below graphically represents the pre-treatment, mid-treatment, and post-treatment mite drop counts for each hive.

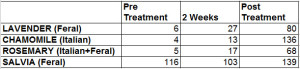

The actual numbers for the counts are in the table below.

As you can see, the post treatment numbers, at least initially, look like the treatment was ineffective, the mite counts are well above recommended treatment thresholds [1]. However, after spending some time looking at the numbers, and really thinking about what’s going on, both with the bees, and the mites at this time of year, it may not all be as horrendous as it looks at first. I won’t argue that it’s not bad, but it could be worse.

When I pulled the latest mite boards, my initial reaction was surprise, the post treatment numbers weren’t at all what I expected to see.

Surprise then quickly, and briefly, turned to panic, as fellow beekeeper Lisa will attest to, when I immediately fired off an email to her about her treatment experiences last fall.

The whole point of treating our bees in mid-August was to get the mite count down so the bees have the best chance of building a healthy last round of summer bees in late September, who will then raise the critical winter bee populations in October.

Healthy populations of late summer bees are critical to ensure the health of a hive that's preparing for winter

If these September nurse bees aren’t healthy, and there aren’t enough of them to rear a substantial population of winter bees, these hives will all be at significant risk of failing before the end of the year.

Graphing the data though allowed me to consider the numbers a little differently, and after staring at it for a while, I began to think about the numbers in context. Why had Salvia’s mite count barely changed from the start of treatment? Was Thymol that useless? Most beekeepers we’ve spoken to swear by it, especially as a warm-weather treatment. Why had Chamomile, that hardly had any mites at the start of treatment, and based on standard treatment thresholds didn’t even need to be treated, now find itself with mite counts that rival the Salvia colony!?

Let’s start by looking at the Salvia hive. The mite burden in this hive at the start of treatment was the impetus for us deciding to treat the bees in our apiary in the first place. Look at the pre-treatment bar in the graph above, compared to the other colonies. Salvia was the first hive we set up this year, had been raising brood longer, had been producing a robust population of drones all season until just a couple of weeks ago, and all that translated into supporting a burgeoning mite population. There was no question we needed to consider treating that colony.

I really questioned the rationale of treating all the hives at this point though, just based on mite counts, as the other hives were all below the approximately 30 mites/24 hours treatment threshold that had been previously recommended to us.

Now look at the red bars, the mid-treatment levels after two weeks of Thymol in the hives. There’s an ever so slight dip in Salvia, which could quite simply be sampling error, or a slight shift in mite count due to population change in the hive (decreased drone production mid-treatment), or ambient temperatures affecting grooming activity of the bees. There are many variables, so who knows? However, also note that the mite drop counts for the other three hives appeared to be slightly increased at that same point in time.

At the 2 week treatment mark, we applied a second round of Thymomite strips to the hives. We’d treated toward the low end of the dose range for the first round. After the mid-treatment count though, I elected to increase the dose in all of the hives. Feeling like we’re fighting against the calendar, and wanting desperately to get the mite levels down, we hoped this would just be a little extra insurance. As such the two smaller colonies received 1 whole strip, and the two large colonies received two strips during the second half of treatment.

So yesterday, the first post-treatment sticky board I pulled was from under the Chamomile hive, and I was horrified to see how many mites were stuck to the board.

The Chamomile hive had few mites at the start of treatment, I expected the board to be more or less clean after treatment. I was wrong, very wrong.

This hive has always had very few mites, but has also always been our smallest colony. Although natural drop counts aren’t quantitative, multiple counts over time do demonstrate whether or not mite levels are increasing or decreasing within a particular hive.

The Chamomile bees were packaged Italian bees that arrived in May, and unlike their neighbor’s, Rosemary, who arrived the same day, Chamomile was very slow to build up population all through summer.

What the graph doesn’t show is that Chamomile has about 30% of the population of bees as Salvia, so although their post-treatment mite counts are now equivalent, that suggests Chamomile’s population of bees could now be considered to be roughly THREE TIMES MORE INFESTED than Salvia. Their mite population seems to have exploded, with a 3300% increase in mites in the last four weeks, in the presence of Thymol!

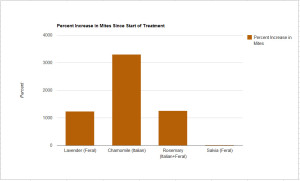

Looking at the difference in mite counts before treatment, and afterwards, it's clear that Chamomile's count has skyrocketed...but Salvia's percent increase is MUCH less, but why?

Using an online Varroa Calculator, this returns an estimate of 5,400 mites in the Chamomile colony, well above a presumed tolerable pre-treatment limit of 2,000 mites per colony.

Note however, Salvia’s mite count on the other hand has held relatively steady, only increasing 20% in the same time period. We’d prefer there was no increase, but this time of year is when Varroa mites really ramp up their reproduction. Bees are also decreasing the sizes of their colonies in preparation for winter, and weaker colonies can quickly become overwhelmed by burgeoning mite populations.

Lavender and Rosemary both have similar numbers of total bees in their hives, and the mite counts have increased at a similar rate, just over 1200% since the start of treatment.

Trying to Make Sense of the Mite Counts

With the exception of Rosemary throwing the Thymomite out of the hive, all four hives received the same treatment, dose adjusted for population, at the same time, for the same period, under the same climatic conditions. So why the variability in increasing mite levels?

The primary differences between these four hives are total colony size/strength, with Salvia > Rosemary > Lavender > Chamomile, and the source of the Queens, and worker bees.

The Chamomile hive is comprised of very blonde Italian bees, with a pure Italian Queen, from one of our packages that arrived in May.

Two of colonies have Italian Queens, bred at commercial apiaries. The other two Queens are feral, locally mated Queens.

The Rosemary hive was also a package colony, from the same commercial apiary, comprised of Italian bees, but seemed to gain significant population from our large feral colony situated immediately next to them on the hive stand. We noted a lot of drift into this hive from Salvia early on, and the Rosemary colony has been stronger all season as a result. Looking in Rosemary’s hive, it’s easy to see a clear mix of very blonde Italian bees, and lots of dark stripey bees from Salvia.

The feral Salvia and Lavender hives were both sourced from the same colony, just across the creek from us. The main difference between these two is that Salvia has a Queen that survived last winter, which swarmed in late March. The Lavender hive swarmed with a virgin Queen in April, from the same colony. The Lavender colony has been building up population for approximately 1 month less than Salvia.

When we first were attending guild meetings and lectures, every beekeeper we met touted the value of ‘feral’, versus ‘package’ honey bee colonies. Is it possible that part of what we’re seeing here is that the Salvia hive, despite a high mite burden for most of summer, and seemingly increasing mite populations in our hives, is actually, with a little help from the Thymol, simply better able as a colony to cope with their mite infestation?

It’s difficult to know for certain, because our data set simply isn’t big enough, however, it may help to explain some of the difference we now see in trending mite populations between Salvia, and Chamomile. Our feral colonies, until arriving in our apiary, had never been treated, so it’s reasonable to expect they have adapted at least somewhat to the presence of Varroa in their environment, or they wouldn’t be here.

Even if all the hives are removing diseased pupae though, a weaker hive may simply not be able to keep up during the period of escalating mite populations in the fall. As such, that would imply that this is very bad news for Chamomile. This has been a relatively weak colony since its arrival, and looking at this colony as a whole, in conjunction with the current overwhelming mite counts, my prediction is this colony, left as is, is highly likely to fail in the coming weeks.

Although mite counts have increased for all of the colonies despite treatment, without treatment we’d expect the counts would have been much higher (this is where having a control colony in our apiary would have been informative).

Salvia, the colony that survived last winter, ironically now seems to be the best off of all our hives, and yet at the start of treatment it was the colony we were most concerned about. Lavender, although mite counts have increased, isn’t as bad off as our ‘pure’ Italian colony, and Rosemary, who has received an influx of feral workers, despite having an Italian Queen, seems to be holding its own as well as Lavender. Are the feral bees conferring an advantage to the colonies that have them? Are we simply seeing a colony’s ability to cope with mites based on colony strength, or origin? Or could the increased mite counts in the smaller colonies be a consequence of robbing, and an influx of mites into those hives? It’s likely a combination of all those things. Interpreting the effects, and effectiveness of the Thymol treatment, would have been so much more straightforward if the mite counts had declined.

The Next Step?

The more important question now though, is where to go from here? The mite counts are still too high. We’re now trying to decide if perhaps we should try retreating again with the Thymol, as although it hasn’t decreased the mite counts, yet, it may at least be preventing them from escalating further (I shudder to think how high Chamomile’s count may have been if untreated). Alternatively we could follow up with a different organic acid treatment, perhaps either Formic Acid, or Oxalic Acid a little later in the season.

For Chamomile, our weakest hive, as this hive has struggled relative to the other hives all season, and it’s mite population is exploding, we are seriously considering replacing their Queen with a mated Queen of a difference race of bee. Perhaps either Russian, or Carniolan. It’s too late to let this colony raise their own new Queen as drone season here is done, and she would risk a failed mating.

Requeening this colony now, while there’s still time to raise winter bees, may be the best hope for the Chamomile colony to survive, without having to bombard it excessively with treatments.

I wish we could fast forward to the end of February 2012 to see how this all turns out. We’d hope that at least the Salvia colony would survive winter again this year, and any hive that proves its mettle, and survives this winter will be split at the beginning of the season next year. Much of our Varroa management in the future we’d like to base on splits, and breaks in the brood cycle. The consequence of that, we hope, is that we’ll also be selecting for stronger bees. The question is, who will survive?

Very few full frames of capped honey remain in any of the hives. Fall feeding will help the bees as they raise their winter bee populations

While we decide which path to take next to best help our colonies, the more pressing issue now is colony nutrition. The other horror in the hives this weekend was the discovery that our bees have consumed more than half of their honey stores in just the last month, and we’re squarely in the middle of a nectar dearth. How we’re handling fall feeding of our colonies though, and why, we’ll save for our next bee post.

—————————–

[1] Oliver, Randy. 2006. IPM 4, Fighting Varroa 4: Reconnaissance Mite Sampling Methods and Thresholds

Hmm… interesting and disappointing.

Am I understanding correctly that you are suggesting the possibility that robber bees may have introduced more mites into the smaller colonies?

Half the honey stores gone already? How do feral colonies manage to build up enough honey to survive the winter on their own?

Yes. If robbing is occurring in an apiary, phoretic mites can be carried in on robber bees to the hive being robbed, and cause a sudden surge in mites in that hive. That said though, we’ve had robbing screens on since the start of treatment because of the yellow jacket problem in the apiary. We haven’t seen any robbing going on with our hives, but it’s still possible that it did occur, and we missed it. Just something we have to consider.

As for food, sometimes feral colonies will fail if they don’t have enough stores, just like a managed colony can. Part of the issue now is that where there was one colony (that we knew of) across the creek last year, we’ve now added four more colonies in the same foraging area, and my neighbor added two more! That translates into many more bees in a small area, competing for the same naturally available resources. This year has been problematic weather-wise on the coast too, affecting native bloom periods and duration, and we’re rural, so have less food resources available as a whole for the colonies to start with. In a good year, it may not be a problem, but honey in general seems to have been low for beekeepers here this year, and most blame the weather, but bees also consume their stores much faster when struggling with Varroa. So until the mites decrease, supporting our bees nutritionally will be important.

Really interesting read, Clare. Bee keeping is a pretty complicated endeavor and a lot to keep up on. You really have to be quite the investigator and scientist too. I have so many different kinds of bees in my garden, that you have me really interested about both their health, and where they reside. I may start some investigating too.

A friend who used to keep bees years ago said he stopped when Varroa mites first arrived because beekeeping wasn’t enjoyable anymore. I love a challenge, but I do think these mites have significantly complicated beekeeping for a lot of beekeepers, and at times like this it does become quite frustrating when your best efforts aren’t enough. Hopefully we can pull these hives through, and with some changes in management next year, avoid having these nasty mites get such a stranglehold on our colonies.

Clare,

I’d give up on the thymol altogether. It does not work at least in your hives. A lot of beekeeper around here do confectioners sugar on the bees.

I have a new bottom board, it might help too. Mine is a small hive beetle trap, the bottom is filled with cooking oil. In two days I killed almost 100 beetles! My thoughts were 60 female beetles, up to 60,000 larva = dead hive. Any way when the mites fall they should die too. Not found any mites in there yet, but I’ve been too busy to look closely.

Sure hope you get this under control!

That’s the thing though, if you just look at the Salvia hive, the Thymol did work. The count didn’t drop, but the mites didn’t escalate like they did in the other hives. It’s just not enough, but that could be a function of mite burden, or weather conditions at the time of treatment. It’s just that without an untreated control, we can’t say where mite levels would have been if we had NOT treated. I suspect they’d be even higher.

What we do know is powdered sugar doesn’t work. Not this late in the season, and not once mite levels are this high. The sugar only knocks off phoretic mites, those attached to adult bees, and generally it’s presumed that those are only 5% of the mites in the hives. Sugar can’t reach the mites in the cells, the other 95%! Powdered sugar is a preventative, not a cure, and not always a reliable one.

We will try sugar in the spring though, once mite levels are low, to help stop their numbers from climbing as fast through spring and summer. In hindsight we should have dusted Salvia at the time we hived the swarm. The trouble with Varroa mites, is the population doubles every 27 days, so you have to catch it early for sugar to have an effect.

We used drone trapping earlier this year to also prevent the mites from ramping up too quickly.

We’ll do another count in a week, and see where we are at, and formulate a plan B in the meantime 😉

Three things I wonder about:

1. Could the very close proximity of your hives be inviting drifting, and cross contamination? In the age of varroa, would it make more sense to space the hives further apart?

2. Would disrupting the bees’ brood cycle do any good, in terms of breaking the mites’ breeding cycle?

3. How bad are your winters? We have flowers blooming almost all year ’round, so we don’t worry about feeding bees. I understand that the Loquat bloom is about to start. Maybe you’re okay for food stores.

4. I personally balk at requeening, but it really comes down to an irrational squeamishness on my part. I hate killing queens.

Well, this is why I’m an artist and not a scientist. I can’t always be trusted with simple math.

Drift is certainly possible, as is robbing. That’s actually why we chose to treat all the hives, and not just the infested Salvia hive. Hive spacing within the apiary might help for drift, but not for robbing. We have an unknown number of feral colonies in the area, and the robbers may not necessarily be neighbor bees. Moving the hives now also won’t address the current mite levels.

We could disrupt the brood cycle, we could cage the queen, but that takes time, and timing that now seems questionable, especially as we’re so close to winter bee production. It certainly could backfire.

Requeening with a mated Queen won’t really break the brood cycle, but might at least give us a stronger queen, who may in turn produce workers that cope better with Varroa than the bees currently in Chamomile, but we’d still need to address the current mite load.

We are definitely not ok for food stores. You have the advantage that you’re urban, and your bees have all the East Bay cultivated gardens to forage in all year. We have almost nothing here blooming in the mountains right now, other than Asters, which produce low quality pollen, and the nectar doesn’t store well. Most of what’s up here is oak, and redwood, and some grasses. Up here everyone dreads the dearth at the end of summer if their bees get caught short. Interim feeding with pollen and syrup may be necessary, both because of the dearth, and because our bees are using more stores while contending with the mites. Chamomile only has 1 1/2 frames of honey left.

Dang! I wish I lived closer. I’d give you some frames of honey.

We’ve got formic acid pads, left over from last year. Not sure about your local temperatures, but if you want to try this, they’re all yours.

Varroa mites really suck. I guess we can count ourselves lucky that we don’t have to deal with a lot of the other pests.

Mites do suck! We have a bee guild meeting on Monday, and I’ll run the retreatment idea past some more seasoned beekeepers. If we go formic, I’ll be in touch! 🙂

Clare it is always fascinating reading about the bees…so much to know and you certainly have researched and are committed to your bees. I would love to learn more about the types of bees I have here in my gardens…but that is for my winter and next spring…

So much to know, and clearly so much we don’t know! I wish the bees could talk sometimes, it would make knowing what to do next so much more straightforward! 😉

Wow, this really is like a thriller. And I can’t believe how complicated it is! Good luck with the fall/winter, I can’t wait to here more.

P.S. How are the turkeys?

The turkeys are much better off than the bees, and doing great! It is a thriller isn’t it? I wish I could skip ahead to the last chapter 😛

Hi,

I do like to see updates on your Bees; it’s so amazing having little glimpses into their lives.

It’s a shame to see the mite levels appear to have got out of control, and I have to agree that no doubt the wild colonies will be stronger than the farm-bred ones. After all if they’ve managed to survive in the wild then there must be something aiding to their success and one of those aspects will be their ability to keep the mites away.

Is it possible to put some of the wild bees into your Italians, so they’re able to teach them? Or would the italians just kill them as intruders? You mentioned that there were some drifting, how is it that those that crossed over were not attacked?

Anyway, I’m just ranting now 🙂

I do hope they all make it through winter…

We can transfer some of the feral bees to the Italian colony, and we are considering that. For winter it’s ideal if all your hives are of similar strength. Some beekeepers will balance their hives this time of year, by taking frames of capped brood (unhatched baby bees), and putting them into weaker colonies. The nurse bees in the new colony will care for the brood just as they would any baby bees in the hive, and when the bees hatch, they orient to the new hive. This is probably the easiest way to boost population in a weak hive, and part of why we decided in spring to have more than one colony, so we have that option. We’d resisted doing it earlier though because our strongest hive had a mite problem. Now they all have a mite problem, it probably doesn’t matter much 😛

As for drift, workers that return to the wrong hive may be attacked, but usually, if they return carrying food they can usually get past the guard bees at the entrance. The guards are more alert to bees that show up empty handed, and will attack those as they presume they are there to rob the hive.

How disappointing. Interesting, though, that those bees worked so hard to get that out of their hive! I hope your bees do well through the winter – seems you’re getting into a crunch now that fall has arrived. Like Donna above, reading about your bees really makes me wonder about the bees I see around here.

I felt bad watching the bees struggle to get that Thymol over the robbing screen. They really were determined that it shouldn’t be there, and I can’t blame them. I’d have felt better about using it if it had more of an effect, but it’s possible that we’re just having an exceptional time with Varroa this season. Hopefully we can get the mites down quickly while the bees can still recover their populations before winter.

My head hurts a bit after reading your post and trying to make sense of what’s happening here. I’m sure I’ve said this before but I really had no idea how complicated having bees would be. You’ve put in a tremendous amount of thought and effort and I sincerely hope your colonies make it through the winter. It would be such a shame to lose them now.

I’m sorry Marguerite, I did think of posting an Ibuprofen warning at the beginning of the post, it gave me a headache just trying to fathom how on earth the mite counts went up so much in three hives, and not the other. It’s part of my innate need to know the ‘why’ of things. I should probably just accept that it is what it is, and not over think things 😛

Hi Clare, a swarm of honey bees unexpectedly relocated to my bee boxes recently and I’m quickly trying to figure out how to keep them alive as the fall rains being here in the Seattle arera. I’ll be reading your posts on bees today. Thanks!

Hi Kathy, I’ll be doing a late fall feeding post next week. It’s raining here too, and we’ve had a long nectar dearth this fall, and our bees are getting caught short on food. My recommendations for right now would be 1) on a warm day, you might want to powdered-sugar dust the new colony to knock off any phoretic mites that have come with them. Treating with anything stronger at the moment will affect brood rearing. Ideally you’d like it to be over 65F to do this, and do it quickly to avoid chilling any eggs/larvae. 2) and probably most importantly, I’d feed. Feed Feed Feed Feed FEEEEEED! These bees will have no reserves built up for winter, and there isn’t much time left for building up stores and rearing of winter bees. These late swarms are challenging. I’ll post a recipe for fondant next week, that you can keep in the hive as emergency feed all through winter, but at a minimum I would offer some sugar water (2:1) now, and if you have some available near you, even a pollen patty on the top bars as a source of protein. If you have any frozen frames of pollen that you could thaw, more the better. If you’re in an urban area, I know pollen and nectar may not be in too short a supply, but with the bad weather, they may not be able to fly as much to forage. Good luck!