As promised in a previous post, this Fowl Friday we’re going to take a little diversion, and look more closely at how chicken eggs are formed.

If you read our Pullet Eggs post, I mentioned that young chickens first coming into lay can often have little egg-laying mishaps. Sometimes a young pullet will just lay an egg yolk wrapped in a membrane, and no shell. Some eggs are strangely shaped, or may contain no yolk, or a double yolk.

By the time we’re done with this post, we hope you have a slightly better understanding, from the hen’s perspective, as to what is involved in producing wonderful farm-fresh eggs.

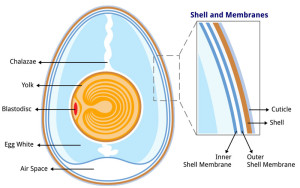

To better understand where eggs come from, and how they are formed, it’s necessary to start with some basic anatomy. The egg itself is composed of key structures, each of which is formed at a different point during it’s journey from the hen’s ovary, through the oviduct.

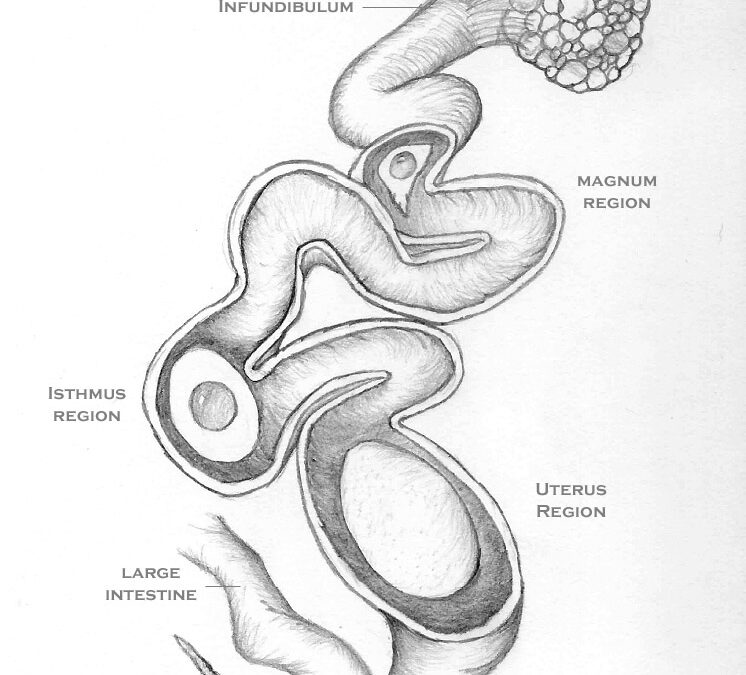

Birds and mammals have some significant differences in oviductal anatomy. The sketch below represents the left oviduct of a typical hen, and the path each egg takes, from the ovary, until it is ready to be laid.

Sketch of the process of egg formation within a hen's oviduct (click image to enlarge) Image © Curbstone Valley Farm

Where mammals typically have paired ovaries and oviducts, most birds, including chickens, only have a functioning left oviduct.

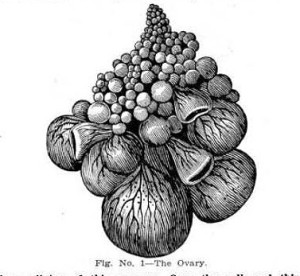

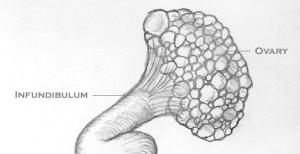

Ovary

An egg’s journey begins at the ovary, which contains the developing follicles, collectively resembling a bunch of grapes. Each hen has a finite number of follicles, as she has all the follicles she will ever have at the time she hatches. Hens are most productive during their first few years of life, typically laying an egg every 1-3 days, depending on breed and age. Hens will continue to lay eggs as they get older, however, total egg production, and egg quality, decreases with age.

Infundibulum

Once the ovum is released from the ovary, it is drawn into the infundibulum, at the proximal end of the oviduct.

From here, the ovum is propelled distally through the oviduct. In the presence of a rooster, fertilization of the ovum takes place in the infundibulum, before most other components of the hen’s egg are formed. Chalaza, the white protein ‘ropes’ that anchor the yolk in the center of the egg white, first appear as fine filaments while the ovum is in the infundibulum.

It takes less than 30 minutes for the egg to be moved from the infundibulum to the magnum region of the oviduct.

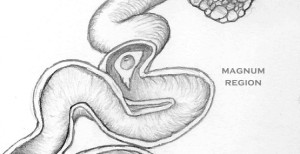

Magnum

Within in the magnum, the egg receives a coating of albumen (egg white).

This process takes approximately three hours, at which point the egg makes its way to the Isthmus.

Isthmus

In the isthmus, shell membranes are deposited around the egg, and its albumen coating.

The shell membranes, which contribute to the air cell formation, are deposited around the egg in the Isthmus region

This is a relatively quick process, taking approximately one hour, before the egg makes its way to the uterus, or shell gland region.

Uterus

In the uterus the outer shell, and shell color, is deposited.

The hard outer shell, and shell pigments, are deposited around the shell membranes in the Uterus region

The egg spends the greatest period of time in the uterus region, as it takes approximately 20 hours to complete egg shell, and pigment, deposition.

The shell is composed primarily of calcium carbonate derived from the hen’s own body stores of calcium (47%), and dietary calcium (53%). As more than half of the required calcium comes from food, it is important that a hen’s layer-diet is rich in calcium to help ensure that strong eggshells are formed.

Vagina

The vagina isn’t involved in egg formation per se, however, a protective shell coating, called the cuticle, or ‘bloom’, is deposited around the egg just prior to laying. This layer is somewhat oily in texture, and facilitates egg laying, and helps protect the egg from bacterial invasion as it is passed through the cloaca.

The total time to form an egg is approximately 25 hours. For hens that lay an egg each day, after an egg is laid in the morning, between 30-75 minutes later, the next ovum is released into the infundibulum, and the process begins again.

When things go Awry

Now that we have a better understanding of egg formation, we can also better interpret where in the process things are amiss when an anomalous egg is laid.

Double Yolks

Occasionally, a hen will produce double-yolked eggs. Double-yolking sometimes occurs in older hens, but may occur in young hens that release two ova in rapid succession. In our first flock of buff orpingtons, one pullet routinely would lay over-sized eggs, containing two yolks. Double yolked eggs are perfectly edible, but are not suitable for breeding. Although the eggs tend to be larger, they may lack sufficient nutrients and space to support the development of two chicks, and twin chicks rarely successfully hatch without intervention.

Yolk-less Eggs

A young pullet may produce a yolk-less egg. This usually occurs when a fragment of ovarian tissue, or oviductal lining sloughs, and stimulates the secreting glands in the magnum to produce albumen. The rest of the egg-formation process may then continue as normal, except that an egg without a yolk is laid.

Blood Spots and Meat Spots

These are rarely seen in commercially produced eggs, as when the eggs are candled, those containing blood spots and meat spots are rejected. The eggs are still perfectly edible, but are rejected for aesthetic reasons. Blood spots are normally associated with the egg yolk. Rupture of tiny vessels during ovulation is typically the cause of blood spots. If you raise your own hens for eggs you may notice these from time to time.

Meat spots are usually brown in color and are typically associated with the egg white. Because the albumen is deposited around the egg in the magnum of the oviduct, these spots aren’t due to vessel rupture at ovulation. They are formed when small pieces of the of the oviductal lining slough as the egg passes through.

Thin-Shelled or Shell-less Eggs

Occasionally eggs are laid with thin shells, or may be lacking a shell entirely. A shell-less egg doesn’t typically look like an egg would if you cracked an egg open. Usually the yolk and albumen are at least encased in the shell membrane, but the calcium carbonate hard shell is not deposited. This usually results in an egg that has the appearance of a small water balloon. These are occasionally found in young pullets first coming into lay, but providing the pullet is otherwise healthy, this problem should quickly resolve. If the problem persists however, a veterinarian should be consulted, as there are some poultry diseases, and some poultry medications, that can cause this phenomenon. An occasionally shell-less egg isn’t necessarily cause for alarm though, and shell-less or thin-shelled eggs are more likely to be related to diet and/or aging. As these eggs lack a complete protective outer coating, they should not be consumed.

This egg was recently laid by one of our older orchard hens.

The thin shell was easily removed, revealing that the rest of the egg was formed normally.

On the other side of the same shell it is clear that pigment was not evenly deposited.

Note the lighter region on the shell where the pigment was not evenly deposited, and the granular aggregate on the shell surface

This is the first time we’ve seen an egg like this from the orchard hens, one of whom is coming back online after a molt. As a one-off, this isn’t particularly concerning, but if this hen continues to lay eggs with these defects, it warrants further investigation. As we know that both shell and pigment are deposited within the uterus region, if any more eggs are laid with these defects, it may suggest a problem within that hen’s uterus.

Hopefully you now know a little more about how chicken eggs are formed. One question still remains though, who came first…?

You’re an eggs-pert!

Couldn’t resist 🙂

Haha…you ‘cracked’ a joke 😛

Wow! You ARE an eggspert! This is more than I ever really considered about eggs.

Thanks for sharing,

Elizabeth

I think a lot of us don’t really think about eggs, beyond eating them. Keeping chickens though, gives us a slightly different perspective on eggs, and quite an appreciation for what it takes just to make just one!

As usual, this is sooo informative & interesting!

PS, the revised CV site is nice too, with all the share hot links easily accessible to the right… you have already done a swell job on it Clare…full of content, but uncluttered with easy navigation, etc. It’s really great and a pleasure to read!

Thank you Susan, considering how long I resisted keeping a blog, I’ve discovered I actually enjoy it 😛

Excellent!

Having grown up in a rural town, we used to raise our own chickens and I remember my grandmother would cook the grape-like bunch of yellow balls(ovary). As a kid I had the privilege to eat them. 🙂

Interesting, I don’t think I’ve ever seen anyone cook a hen’s ovary before!

Thanks Clare. Again I learnt a lot from your post. As a backyarder with a few birds it’s good to hear what’s normal and what’s not.

With our first pullets, we saw a lot of what the range of normal is in newly laying birds. It can be a little disconcerting though as a chicken raiser the first time you encounter an egg without all of its component parts, at least until you understand why, and how it happens.

So glad I stopped in today. This was so interesting and informative. I love chickens and never looked into how eggs are produced, so fascinating. Maybe if I had a few hens, I may have, but you laid it out so well. It was easy to understand. The comic was adorable.

Thanks for dropping in Donna. I can take credit for the sketch of the oviduct, but not the cartoon, I’m not that talented 😛 I thought the cartoon was rather cute though.

Hmmmm…. Well…. I am completely educated on the matter. However, I’m not sure I’ll be able to continue my tradition of eating a hard-boiled egg every morning. Thanks for the biology lesson!

Awww FG, I hope I didn’t put you off breakfast. 🙁

Thanks for the great info! I’m still looking forward to my first egg. The pullets will be 19 weeks old on Monday. The whole neighborhood is probably going to hear about it when I find that first egg 🙂

It won’t be very long now Jackie, and your girls will be laying lots of lovely fresh eggs! I can’t believe they’re 19 weeks already!

OK Clare, I am in awe with this amazing post and your wealth of knowledge. A huge egg lover (perfect protein), always wondered! I always buy organic (usually at Costco and occasionally find blood spots, which don’t disturb me or should it). I like brown eggs … is there a difference between white/brown or a huge difference in taste with blue, etc. with each breed. Chucked with Kyna’s first comment … Thank you fun ‘egg-spert’!

I used to hear the myth as a child that the blood spots in the yolk were the start of a baby chick. It was just that, myth, as it happens in unfertilized eggs too. As a child the blood spots bothered me, but knowing what really causes them, I’m not bothered in the least.

There really is no difference in egg flavor, quality, or nutritional content with different colored eggs. However, in the US at least, the white leghorn, which lays white-shelled eggs, is the most common breed for egg-laying used in commercial poultry operations. I think some of the preference for brown eggs here, is that we expect as consumers that brown egg laying chickens weren’t raised under such intensive farming conditions. It’s not a guarantee though. Sourcing eggs from local producers, where you can get to know the farms and farmers who produce the eggs, is the only way to know how their hens are kept.

Clare, What a great science lesson! My mother always said that you can learn something new every day if you go to the right place to learn it — and for me today, this was clearly the right place. Thanks.

Thank you Jean, I was always told it’s important to learn something new every day to help keep your brain fit. That’s why I enjoy reading so many blogs, including yours!

Now I know why I used to see little bits of red in the yoke or brown in the white of the egg. As a child that used to put me off eating the eggs. Great informative post Clare.

Just to let you know that for the past 2 weeks your feed burner has not been sending me email updates as I subscribe by email. Not to worry as I have you on my google reader and blotanical but I miss getting those emails. Not sure if the problem is at my end – I checked my spam folder and they’re not there either. I thought I should mention it incase someone was only getting note of your new posts through email.

I’m not sure what’s up with our email updates. It seems some readers are getting them, and others are not. We’ve noticed a disproportionate number of readers with Gmail email accounts aren’t receiving notifications at the moment, and the messages aren’t going to spam folders either. I tried upgrading WordPress, and changing the email notifier plugin, but it doesn’t seem to have fixed it 🙁 We’ll keep trying though!

Everything I ever wanted to know about egg formation but was too afraid to ask! Thanks for sharing your eggspertise!

Another very interesting post. We had purchased eggs awhile ago and several of the eggs had blood spots which always kind of grossed me out a bit. Good to know it’s nothing to bothered about.

Simply amazing … I never knew the finer detail on just how an egg is produced, but I’m now enlightened! It’s fascinating stuff … this post would be a great tool for teaching this very topic to kids.

fascinating…i love brown speckly eggs!

I always learn so much when I visit your blog, and so interesting! Thank you.

Dear Clare, I can only marvel at the lengths to which you go to provide such marvellously informative and detailed postings, and all illustrated so beautifully. What you have said here has dispelled many of the myths that I have grown up with, so it has been good to separate fact from fiction. Eggsellent!!

I’m hoping that someone will ask me a question about eggs, so I can show off my new found knowledge. 🙂 Thanks!

Clare, you’ve outdone yourself. This post is most interesting and educational! However, I’m exhausted thinking of those poor hens laying eggs one after the other.

This is absolutely fascinating….I have 6 fresh eggs on my counter from my sister’s chickens. I will never look at another egg or chicken the same way again 🙂

25 hours to produce the egg? Then straight back to work on the next one! You’ve given me a whole new perspective Clare and I won’t take eggs (or chickens for that matter)for granted from here on!

Your post definitely makes me appreciate eggs more. It’s so easy to take food for granted if you don’t know eggsactly where it comes from. So thanks for the detailed and well-presented biology lesson.

Great little science lesson. Thanks as always. When an old roommate of mine had chickens I was amazed at how they produced basically an egg a day. And now I see they are in fact like little factories the way they churn them out. Very interesting.

That you did (some of) the drawings yourself – I take my hat off to you! Detailed and accurate. Must have taken you almost as long to draw, as it took the hen to make the egg ;>)