Although we primarily keep bees for pollination, we’d be lying if we didn’t admit that at some point we also hoped to harvest at least some honey. Last year, as the colonies were building up, we left the honey stores with the bees.

We’ve had a smackeral or two of honey along the way, but not nearly enough to keep your average bear happy.

In early spring we thought we might be able to harvest quite a bit of honey, but swarm season set off with a roar, and due to poor timing on our part, we lost most of our spring honey to the swarms.

Finally though, this last weekend we managed to eek out an actual honey harvest!

This was our last opportunity for the year to take any honey, if there was enough, so the bees would still have time to restock their reserves before the weather changes.

Most of the hives were doing well, except for Salvia, as we mentioned in our last post. Relative to the population of bees, Salvia had quite a bit of honey, so we took a few frames from that hive. The Lavender and Chamomile hives both seemed to have enough stocked for this time of year, but neither seemed to have what we’d call a ‘surplus’, so we left their honey alone.

Then we looked into the Rosemary hive. This colony, split from Salvia in February, got an early start to the season. By April, Rosemary was building up fast. After the swarms, and reshuffling of resources around the apiary between the hives, there really wasn’t any extra honey to take though. However, we added a Queen excluder to a couple of the hives that seemed most likely to produce a surplus later in the year.

We’re still undecided whether we’ll continue to use Queen excluders routinely or not. For the Rosemary hive it seemed to work great. But for Chamomile, a less robust colony, despite checkerboarding some nectar frames above the excluder, the bees refused to move up.

As soon as we pulled the lid from the Rosemary hive, we were bombarded by some grumpy guard bees. This hive is not short on population, and definitely not short on guards!

As it’s August, it’s also robbing season, so the bees are certainly in a more heightened state of alert. In fact, before we did anything this weekend, we re-installed the robbing screens at the hive entrances. We learned our robbing lessons last year, and we know that taking honey can exacerbate robbing in the apiary.

It was clear the boxes above the Queen excluder were completely full of honey in Rosemary hive, even the outer frames which the bees often don’t bother drawing out, were jam packed with capped honey.

We removed those boxes to assess stores closer to the brood nest. Before taking honey, we want to be sure we aren’t leaving the bees short, and we also wanted to be sure the Queen was still producing plenty of healthy brood.

However, as we got down to the top of the brood nest, the bees really had decided we were up to no good, and even the smoker wasn’t enough to get everyone to calm down. In fact, for the first time I was actually stung THROUGH my leather gloves! The rest of the inspection was just enough to see capped brood, larvae and eggs, and then we swiftly closed the hive back up.

We didn’t leave the apiary empty handed though…

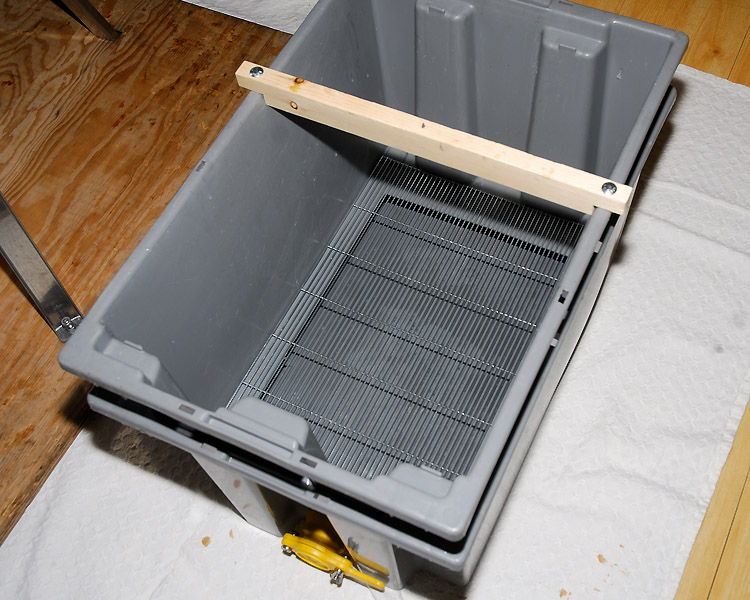

As late summer is robbing season, to minimize the frenzy in the apiary, once the honey frames were bee-free, we quickly tucked them away inside a large marine cooler. This not only protected the frames from the 90 degree heat outside, but the cooler was also impenetrable by bees looking to steal honey, which helped keep the apiary calm and civil. The cooler also has handles at each end, which means the heavy honey haul can be carried by TWO people, instead of one!

Once we hauled the harvest back to the house, it was time to think about getting set up to harvest the frames.

Some of the honey had been stored on foundationless frames, so that honey was simply cut loose from the frame, and cut into sections as comb-honey.

I grew up with honey on the comb, but comb honey seems to be somewhat more rare here. Our neighbors though, who we sourced our first bees from, are happy to have honey in this form, so we sent a large chunk of it in their direction.

The rest of the honey would need to be extracted from the combs though.

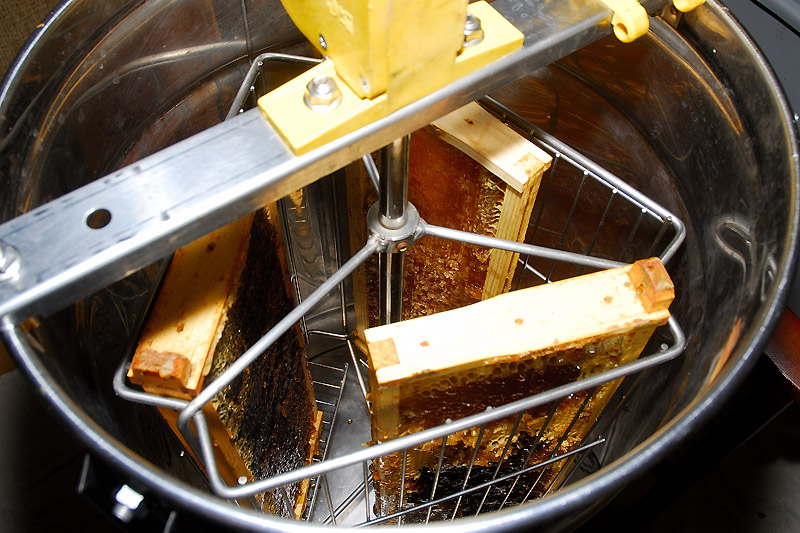

Although for small volumes either a crush-and-strain method, or gravity method, can be used to harvest the honey, we had enough frames this time that we thought an extractor would make harvesting the honey a little easier.

We were fortunate to be able to borrow an extractor, and a decapping tank.

We picked up some honey jars from our exquisitely stocked local farm supply store, along with a harvesting bucket, complete with honey gate for bottling.

Could we have made the bottling bucket? Yes. Any 3-5 gallon food-grade bucket can be fitted with a honey gate.

Setting the extractor up in a bee-free environment was critical, or we’d be mobbed by bees. The decapping tank was set up next to the extractor, and the harvest bucket was set under the honey gate. In the top of the bucket we set a double sieve to strain out any pieces of wax during the extraction.

Once we had everything set up, we cut the cappings from the honey combs.

Any cappings that weren’t cut by the decapping knife, were popped open with a cappings scratcher.

Once uncapped, each frame was set into the basket in the extractor.

Making sure the frames are balanced, much as you would balance a centrifuge, the extraction could begin.

It took a little while, cranking the handle, flipping the frames, and cranking again, but then the honey started to flow!

As frames were emptied, they were set in the decapping tank, along with the bulk of the cappings, so any excess honey that drained out wouldn’t be wasted.

As much work as it’s taken to get even this amount of honey, we weren’t wasting a drop!

It was interesting to note as we decapped more frames, how some of the honey was a significantly different color on one part of the frame versus another.

Makes you wonder what flowers they were foraging on for each of the different colors of honey.

We wanted to keep the honey from the Salvia and Rosemary hives separate, as there can be quite a difference in either flavor, or color, between hives in an apiary.

Once all the frames from one hive had gone through the extractor, the next step was to bottle that honey, before moving on to the next hive’s honey extraction.

With the gate at the bottom of the bucket, and an extra pair of hands, bottling went very quickly.

By the end of the day the counters in the kitchen were getting crowded.

Although this wasn’t a huge honey harvest, we’ve certainly been able to restock our supplies, and are very grateful that this year we have a harvest at all. We’re always a little judicious about taking honey from the bees, as we’d rather the bees ate honey, than sugar water, during the winter months. Bees are struggling enough, we don’t to need make matters worse.

The flavor, and color of this honey, is amazing though. A neighbor asked what we thought the bees had been foraging on to make the honey so flavorful. Presumably it’s a little bit of everything growing up here. From thyme and lavender in the gardens, to various assorted weeds, vegetable blossoms, native plants like the tarweeds and asters that have been in bloom recently, and whatever may be in bloom in nearby gardens.

The flavor of Rosemary’s honey is very complex, and difficult to ascribe to anything specific. It has rich caramel overtones, with hints of floral and citrus-like notes. Salvia’s honey is very similar, just slightly less robust in flavor.

Homegrown honey is truly special, and simply doesn’t compare to mass produced commercial honeys. Seeing the occasional speck of wax in one of our jars, is almost comforting. We know it’s local, it’s pure, it’s strained, not filtered, and depending on the time of year, or the hive, it can be almost any color in the spectrum of honey. You never quite know what you’re going get.

We can’t wait to see how our next harvest looks, and tastes!

“When you go in search of honey you must expect to be stung by bees.” ~ Joseph Joubert

Clare how amazing to see all the work that goes into this…I love the colors of the honey and can only imagine the exquisite taste….I have never had honey straight from the honeycomb…looks so interesting.

Comb honey is a little chewy, and some don’t like that, but it’s fun if you’ve never tried it before. It’s definitely easier to eat once it’s extracted 😉

Clare,

Sweet isn’t it, looks like your set for a little while at least. Nice you were able to separate the blends. We have three types here as well batch one, batch two and my favorite brood comb honey from feral bees.

Don’t let just anyone have some. I sold(he insisted) a bottle to a beekeeper friend that has new hives this year. He wants more his wife now demands he gets more!

This is special honey. I agree, we can’t just give it away (or it would be gone in the blink of an eye) 😛

It was more work to keep each hive’s honey separate, but even with the two hives we took honey from, you can see a difference in color, and appreciate some differences in flavor too.

Glad you showed all of the steps, as I was quite curious! Unfortunately I’m not a big fan of honey, but that could be because I’ve never had “homegrown” — but I do buy local honey, so maybe I do?

Unless you’ve seen honey extracted, I think a lot of people don’t know you get honey out of a hive, and into a jar. 🙂 With the right equipment, it’s very straightforward, but there’s certainly an economy of scale. Unless you can borrow an extractor like we did, it’s not really worth buying one unless you have a fair amount of honey to extract on a regular basis.

Congrats on the honey harvest, Clare! And thanks for showing us the steps that you go through to harvest it. That dark honey looks so yummy.

I skipped the step that took the longest…cleaning the extractor! 😉 That’s part of why it’s not worth using one for just a few frames of honey. If you’re going to use the extractor, it’s worth going the whole hog, and harvesting a lot of honey at once…to make that clean-up at the end worthwhile!

Ouch, stung through the glove! The cooler is a great idea. I’ve been putting the frames in an empty super to carry away from the hive, which works but isn’t bee-proof. Our summer flow is stopped, but with any luck we’ll get some blooming plants soon for a fall flow. I do like the darker honeys, which is how our fall ones usually turn out. They do seem to be more complex, with different nuances.

Great post! I could almost smell the honey and wax myself. 😉

I knew the bees could sting through those gloves, but was a little surprised when one of them succeeded! 😯 The cooler really did work out great that day. It was over 90 degrees out when we were gathering up the frames, and some of them, as they didn’t have foundation, get very fragile in the heat!

What an interesting post! Now I can appreciate what goes into a jar of honey. I never thought about the honey extracting process, but I can say I always thought comb honey was the best. You and your bees put a lot of work into them, and your jars of honey are beautiful!

Honestly, some days, knowing what it takes for the bees to gather nectar, and make honey, all the struggles the bees are having these days, and the work involved to harvest honey, I’m amazed that it’s not $50 a pound. I love comb honey too, it’s really honey the way the bees themselves would eat it! 😉

How interesting! I had no idea this much work went into getting honey. I hope that bee sting is not bothering you. So interesting to see the different color of the honeys. I wouldn’t have thought there would be so much difference since they all forage from around the same area, I would think. But perhaps they each have their own territory, with different flowers.

Fortunately the glove prevented the sting from getting in very deep, and I was able to quickly flick it off my glove with the hive tool. I mostly noticed it a few days later when it started to itch!

The difference in honey, from one hive to the next, in some regions, can be remarkable. Of course, bees that only ever forage on a single nectar source, like an almond orchard, or a citrus orchard, are going to have honey that’s the same color. But when bees are foraging on natural forage, or in urban areas where local gardens provide a diversity of plants, there can be a huge variation in honey color.

Individual bees have floral preferences. Some may prefer to forage on only yellow flowers, others may just focus on lavender, or rosemary. These ‘choices’ made by the bees, and the availability of nectar locally, all can make for some spectacular colors in the honey jar. I suspect our spring honey will have more variation from hive to hive, as there are many more flower species in bloom at that time of year, but the difference between the Salvia and Rosemary hive was even subtly noticeable now. I can’t wait to see the spring crop though! 😉

Wow…that looks like a lot of work. I imagine that’s why honey is as expensive as it is. I’ve considered keeping bee’s but honestly it looks like so much work, not to mention the other considerations like queens missing etc. My hat is off to you. I’m sure it is amazing honey.

It was quite a bit of work, but it was also nice to just get it done. I’m too impatient for crush and strain/gravity for anything other than a couple of honey frames.

If you really want to keep bees, but are concerned that it seems a little overwhelming at first, my best advice is to find a mentor. Someone who can help you get set up, and to be there the first few times you inspect your hives. It sounds like there’s a lot involved, but truth is, most of the learning comes from experience…and besides…it’s fun! 🙂

It’s lovely, just lovely. Your equipment looks so clean and shiny! Everything we have is pretty hard-used.

Well, if the equipment was ours, it would probably look a little well loved too. We borrowed this extractor and decapping tank from one of our local beekeeper’s guilds, and they like to have the equipment returned in the condition it was loaned in 😉

Nothing to add to the other comments – just an appreciation for how well you shared. Looks too complicated for me – one person’s complication is another person’s fascination I guess. I really didn’t know there was this much to it. I do remember the taste and feel of comb honey from a few childhood experiences – very vivid and pleasant ones they were too!

It is a fascination I suppose. I think you do genuinely have to enjoy beekeeping to be a beekeeper. The wonderful thing is that for a day of work, and cleanup, we have a year’s worth, or more, of honey to show for it!

Clare, what a great post. I remember eating honey on a comb as a kid but haven’t seen it available in years. I’ve never really considered how you get the honey out of the combs otherwise but now I know. What an interesting and time consuming process, makes me appreciate every drop of honey even more.

We sold out of the comb honey almost as fast as we harvested it. Next year I think we’ll have more of our honey frames as foundationless, so we can make more comb honey. People either love it or hate it, but those that love it often have a difficult time finding honey on the comb these days.

I really like that you showed the process and the work involved. I read the whole post with intense interest. We have a nationally known bee lady here in our area and I always get my honey from her bee farm. You are so right about the flavor and colors. I have tried so many varieties that her bees made and the taste is so much better. I love your bee posts.

I hope that next year we can be organized enough to take honey a few times throughout the year, providing the bees are doing well of course. I’d love to see how the colors and flavor profiles shift throughout the nectar flows from late winter through mid summer. I do have my suspicions that the honey may be more bitter when the oaks bloom, but that also will depend on what else is blooming at the same time too.