It’s a dreary, drippy, soggy day at Curbstone Valley, and the weather reports seem to suggest that we’ll be lucky to see the sun again by Christmas Day! So, while our fowl strive to stay dry amidst all this nasty weather, I’ve been cozied up indoors, near the fire, rummaging around the literature looking into Santa Cruz’s somewhat rich history in poultry production. Santa Cruz was a relative late-comer to large-scale commercial poultry production, but by the 1920s the county was the fourth highest egg producing region in California.

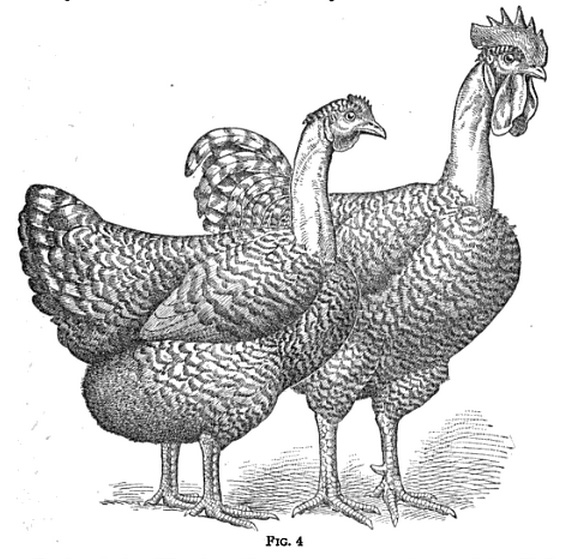

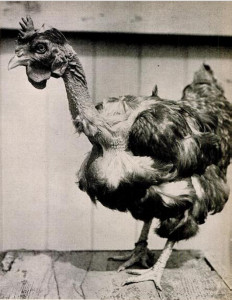

While reading through some old advertisements in the poultry journals, I came across an interesting piece of local folklore. It was claimed that a local back-yard poultry producer in Santa Cruz, California, had successfully managed to cross a Rhode Island Red Hen with a small Holland White Turkey Tom. This mutant chicken and turkey ‘creation’ became locally known as ‘Spencer’s Turken’.

Advertisement for Spencer's Turken Fowl (Spencer's Turken Advertisement (Source: Northwest poultry journal: Volume 27, 1922)

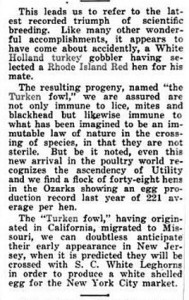

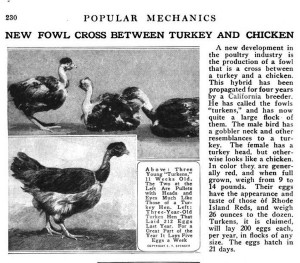

Advertisement for Spencer's Turken Fowl (Spencer's Turken Advertisement (Source: Popular Science 1922)

Advertisement for Spencer's Turken Fowl (Spencer's Turken Advertisement (Source: Popular Science 1924)

The person reportedly responsible for this cross was Zachary Taylor Spencer. Spencer was born in March 1850, in Houlton, Aroostook, Maine, the son of a farmer, Joseph M. Spencer, and his wife Elizabeth. Before arriving in Santa Cruz, Zachary Taylor Spencer had lived in Wakefield, Massachusetts, New Berlin in Florida, where he was employed as a carpenter, and later in Brazoria, Texas, where he worked as a mechanic. Eventually he arrived in California, living in Suisun by 1910 working in retail [1], and in 1911 a reference shows “Z. T. Spencer” as one of numerous founding directors for the Clear Lake Railroad Company in Lakeport [2].

By 1918 Zachary, now almost 70 years old, had finally made Santa Cruz his home, and according to the census in 1920, he was working in a local furniture store.

It was soon thereafter that Spencer was publicly credited with creating his chicken/turkey cross that became known as ‘Spencer’s Turken’, which he advertised heavily.

I’ve taken more than enough biology and genetics courses over the years however, to be rather skeptical of the claims of this particular inter-species cross. The likelihood that Spencer had accidentally produced viable, and fertile, male and female hybrids through an accidental cross, seemed highly unlikely, so I dug further.

I found a pamphlet in the Cornell University Library that appears to have been part of Spencer’s advertising for the breed, where Zachary Spencer claims that on October 1st, 1921, his Turkens took 1st, 2nd, and 3rd prize at the Santa Cruz County Fair, in Watsonville.

In this pamphlet, Spencer explains the origin of the breed as follows:

“In 1918 a baby chicken and baby turkey were given to a little four year old girl as pets; these had the run of the yard and house until they became too large; then were placed in a small pen in the back yard. Never having any other associates these two became fast chums; and it was not until they were nearly grown that it entered the mind of any one that from these two might come a real cross. Thereafter every opportunity was given to that purpose with the result that 13 eggs were laid, fathered by the gobbler.”

It wasn’t long however, before others became skeptical of Spencer’s claims.

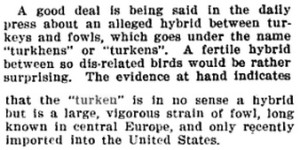

An article published in The Condor in 1922 emphatically declared that Spencer’s Turken was “in no way a hybrid fowl”.

Article refuting Spencer's claim of the origin of the turken (Source: The Condor, Volumes 23-24 By Cooper Ornithological Club, Cooper Ornithological Society. 1922)

Spencer however, continued to sell his Turkens as hybrids. Another article in 1922, published in the Poultry Item, claimed that Spencer’s Turkens were extraordinary, immune to lice and mites and blackhead, and remarkable egg-layers, and the article speculated they may soon be crossed with white leghorns for white egg production.

Clearly tongue-in-cheek however, below this same article the following paragraph was printed by the editor, who obviously had his own doubts regarding Spencer’s claims (not to mention quite the sense of humor):

“And as long as Nature has thrown down the bars in this mating of species, I would suggest it would be an interesting experiment to mate a Belgian Hare buck with a nice big plump Buff Orpington hen. This ought to result in a four legged chicken of rich golden buff plumage or hair and a market fowl par excellence. Two additional legs and second joints would certainly be appreciated by the man who sits at the head of the table and carves while the family make sarcastic remarks. However, we doubt if this offspring of a Hare and Hen would prove much of a layer. Fancy she would only lay at Easter.”

Despite the criticism, Spencer’s Turkens continued to be touted in a 1923 issue of Popular Mechanics, as excellent egg-layers.

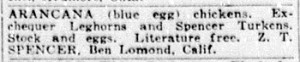

In a 1923 issue of The American Poultry Advocate however, another article cast serious doubt on Spencer’s claims of his chicken and turkey cross, stating the birds, in all likelihood, were in fact a well known breed of Transylvanian Naked-Neck chickens from Eastern Europe, only recently imported into the United States, and not a barnyard cross between a chicken and a turkey at all.

European Naked Neck Fowl had been recently imported to the United States (Source: The Book of Poultry: English fowls. French, Polish, and miscellaneous fowls. By Thomas Fletcher McGrew)

None of this seemed to hamper Spencer though, who even as late as 1927, in an advertisement in the Breckenridge Weekly Democrat on September 9th of that year suggested that Mr. Spencer had relocated from Santa Cruz to Ben Lomond, but was still selling his turkens.

Turken Advertisement (Source: Breckenridge Weekly Democrat (Breckenridge, Tex), No. 5, Ed. 1, Friday, September 9, 1927)

Sure enough, the 1930 United States Federal Census shows a Zachary T. Spencer residing on Margarita Avenue, in Ben Lomond, California.

This is where I finally lose track of not just Zachary Taylor Spencer, aged 81 years in 1930, but of any further references to ‘Spencer’s Turkens’. We’ll likely never know the real source of Spencer’s remarkable Turken fowl, but suffice it to say that as there were then, there are still naked-necked breeds of chickens popular with poultry fanciers today, but their naked necks have been a consequence of genetic mutation, NOT hybrid crosses.

The myth that Spencer’s turkens were created as a cross between a turkey and a chicken seems to have died along with Spencer. It was an interesting local tidbit to find in the old journals, and quite the marketing ploy for the day, albeit deceitful. I must admit though, part of me is rather curious as to how many of his purported Rhode Island Red/Holland Turkey crosses he sold over the years to gullible consumers. Unfortunately, I’m sure that has all since been lost to history. Regardless, it does prove the adage, especially important at this time of year, of buyer beware.

—————

[1] United States Federal Census Records 1850-1930

[2] History of Mendocino and Lake counties, California, with biographical sketches of the leading, men and women of the counties who have been identified with their growth and development from the early days to the present

Such fascinating history! Sounds like that Spencer was quite the enterprising fellow. He even had glowing testimonials. Imagine how well he could have done on Ebay had it been available back then!!!

I would have liked to see a HareHen. I’m guessing it would have been real popular if it had laid chocolate eggs at Easter! 😉

I think harehen sounds better…we were wondering if a chicken and hare cross would be a chare (chair)? 😛 I must admit, if Z T Spencer were around today, I bet he’d have his own infomercial on late night TV, and yes, he’d have to be a seller to be quite wary of on EBay! 😀

Very entertaining piece of detective work. It’s amazing how you found all that information. Carolyn

The genealogist in me had a lot of fun digging through the census records looking for Z T Spencer. I even managed to find him as a baby living with his family in Maine in 1850! He did move around a lot though, and seems to have been married at least twice along the way, although I found no evidence he ever had children. I do rather wonder how/why he ended up in Santa Cruz though.

If it were real, like a zebra/donkey/horse cross, would the offspring not be sterile like the majority of mules, therefore no descendants?

But the real difference is that these fowl are not the same after the scientific Family. I go with the naked neck theory.

Turkey

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Galliformes

Family: Meleagrididae

Genus: Meleagris

Chicken

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Galliformes

Family: Phasianidae

Genus: Gallus

Species: Gallus gallus

Subspecies: Gallus gallus domesticus

I loved your research on this interesting topic. I never heard of the Turken before. Just those that are ready to cook. LOL

You’re right. Assuming the cross yielded viable chicks, they would in all likelihood be sterile. There have been attempts since then to cross the two species, and even though some chicks have hatched, they either haven’t survived long, been sterile, or not been a true ‘cross’…complicated, but basically only chickens hatch. The reality is, with as enterprising as poultry breeders were in the late 19th and early 20th century, if it was that easy to cross a chicken and turkey, everyone would have been doing it, and capitalizing on their new ‘super-chickens’! 😉

I think the best cross would be turken + jackalope + a banana slug. That would be a true Santa Cruz original! :o)

Wow, I’d pay to see that. A yellow naked-necked slug with two feet and antlers LOL. A bananaturkalope? 😛

What a fun post! I’m so glad that naked-neck chicken thing never really caught-on! Ewww…. But the henhare – now THAT would be a good one!

Dear me, I can’t imagine the research you put into this! I’ve done a bit of family genealogy myself and what a load of work that is! I personally have never heard of a naked-necked chicken, but then again, I’m no chicken collector or anything. I must say they aren’t the comeliest creatures I’ve ever seen.

Thanks for the rainy day entertainment – fabulous bit of local lore you uncovered there!

Such a great read! I’m always amazed at how meticulous your research is, and I love those old black & white photos of the Turken Fowl in question. A great way for me to spend an otherwise endlessly rainy, rainy day (yup, it’s been raining here nonstop too, for the last 24 hours, with much more to come at least through Wednesday). Happy Holidays!

Clare, I’ve turned in my grades for the fall semester and am catching up on missed blog posts. I really enjoyed this one. There’s not much to do for entertainment up there in Aroostook County and not many ways to make money — so this tall tale seems to have satisfied both needs! I hope you are managing to keep dry. Happy Holidays!

If the Turkhen charade failed, he could have had me believing they were the long-extinct Dodo bird, now rediscovered in Northern California.

Great post, fun read, Thanks!