Last Friday we spent the afternoon working in the apiary. At the end of February we had split the Salvia colony into our (then empty) Rosemary hive. As a month had since passed, we expected we should see evidence of a new Queen by now, so we needed to see how this colony was progressing. There was also rain forecast over the weekend, and as yet we had not managed to split our Lavender hive this season. As it seems bees prefer to swarm on the first warm sunny day after a rain, we decided we really should split before the weather changed again.

A month ago we divided part of the Salvia colony into the Rosemary hive, hoping they'll make a new Queen

Things got off to a bumpy start in the apiary though. Mr. Curbstone was standing a least 12 feet to the side of the Lavender hive when he was investigated, and promptly stung right on the top of his head, while preparing the smoker.

This was seemingly unprovoked, but the bees seemed a lot more defensive than the last time we manipulated the hives. After removing the stinger, and quickly donning his veil and gloves, we went ahead and set to work.

Splitting Lavender

Recent activity at the entrance to the Lavender hive suggested they were building up dramatically. Like Salvia, the Lavender colony began to build up in January, and the population increase at the entrance over the last few weeks was impressive. Mr. Curbstone’s sting may simply have been a result of the Lavender hive having a surplus of guard bees wary of any activity close to the entrance.

Lavender was an afterswarm captured from the same feral colony as Salvia last April. This colony has never been quite as robust as Salvia, but has been a very strong colony nonetheless (Salvia seems to be the exception when it comes to producing hoards of bees). We know the Lavender Queen is only one year old, as she was a virgin Queen when she arrived, and it was a number of weeks before she began laying eggs.

Our goal on Friday was to see how Lavender was building up so far this season, as we hadn’t checked inside this hive, except to feed, since late last fall. Providing there was ample population, we’d then divide the colony in half, much as we did with our early season split of Salvia in February.

As hive entrance activity was booming, we weren’t surprised to see this when we opened the lid.

The Lavender bees had almost consumed the pollen patties, and fondant we left for them in late winter

Plenty of bees on the Vivaldi board, devouring pollen, and finishing up the last of a fondant block.

The upper hive body, number 5, was primarily honey, with a few undrawn frames, that we transferred after the original Rosemary colony failed in January, and there was clearly plenty of activity.

The bees had been busy drawing out the comb on this frame, with lots of new white wax.

Our overall impression was that Lavender wasn’t quite as overpopulated as Salvia had been when we split that colony in February. Lavender in comparison had much less burr comb built up between frames. Salvia had been packing drone comb in anywhere it would fit, but there was less burr comb to remove in Lavender, which made spring cleanup a little easier.

Unlike Salvia, Lavender only had a few drone pupae between the frames, like this strawberry-eye stage drone

We started by looking for eggs, as eggs are necessary for the colony to raise a new Queen. Eggs also suggest the colony still has a functioning Queen. When scanning for eggs, sometimes it’s easier to find younger uncapped larvae first, and work outwards until eggs are located. Lavender had no shortage of young larvae and eggs. This Queen has definitely been busy.

As we worked through the hive, frames containing larvae and eggs were transferred to the empty Chamomile hive that was robbed out in October. We also moved frames of pollen and honey stores. We tried to be more aggressive with this split than we were with Salvia, dividing the colony more cleanly in half. We somewhat under-split Salvia, as you’ll see later in this post.

With as busy as this colony seemed, we were surprised we hadn’t found any Queen cups. It is swarm season after all. Just as we thought we were about done with this split though, toward the bottom of the brood nest, in the lower corner of a frame, we found this…

…a Queen cell! Not just an empty Queen cup, as we had found in Salvia in February. This was an uncapped Queen cell, with a Queen larvae inside. Between the sun shining in my face, and trying to focus while looking through my veil, I didn’t manage to get a clear shot of the larvae, but you can see the end of this Queen cell is not yet sealed. There was clearly a white Queen larva inside (just not clear in the image, for which I apologise).

Conventional wisdom is that once these cells are capped, no matter what the beekeeper does, the colony is committed to swarming. This was the only Queen cell we found, so hopefully we caught this colony just in time. We’d prefer not to lose the Lavender Queen if we can help it as this colony has done so well for us over winter, and she’s still a relatively young Queen.

When encountering Queen cells during a split, it is usually recommended to move the existing Queen, along with some brood, and bees, to the new hive, and leave the Queen cell, and remaining colony intact in the parent hive. The belief is that this simulates a swarm more closely. Like Salvia though, Lavender is such a large colony for this early in the season that locating the Queen was like looking for a dwarf’s needle in a giant’s haystack, and we didn’t want to leave the hive open for as long as it may take for us to find her. Instead, we moved the uncapped Queen cell to the new Chamomile hive, and were very careful to scan each frame being transferred into the new hive to avoid transferring the Queen.

With the Lavender colony divided more or less evenly to create the new Chamomile colony, now we wait. Just as we did with Rosemary. We’ll keep an eye on entrance activity, and if everything seems normal, we’ll recheck Chamomile in a month. We hope the Queen cell will give them a slight advantage, and help them establish this colony more quickly.

Rechecking Rosemary

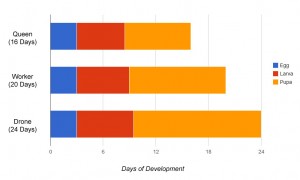

We split Rosemary from the Salvia colony a month ago. It takes 16 days to produce a new Queen, who then has to embark on her mating flight sometime during the following few weeks, return to the hive safely, and hopefully soon thereafter begin laying eggs.

Before checking on the progress of a split, it helps to know what to expect. In the split-development timeline, some things are relatively constant, including the time it takes to produce a Queen, and the time of development of a worker bee from a new egg, to hatch. The variable part is in the middle. Once a Queen hatches, it can be some time before she takes off on her mating flight. Whether or not the Queen can fly is largely dictated by the weather. We’d had a dry start to the year, but we had some significant rainfall events during the month of March, that potentially could have delayed her mating flight.

Considering the timeline to produce a new laying Queen, and factoring in the weather, we hoped at a minimum to see eggs in the Rosemary colony by now, but knew it may still be too early to see capped brood.

Before opening the hive, we observed the hive entrance for activity. Compared to the parent colony, bees exiting and entering Rosemary were relatively few and far between, as you can see in this video that was taken one week after we split out this colony. Salvia on the far left of the hive stand was the parent colony, with Rosemary just to the right.

However, this weekend there were bees entering the Rosemary hive with pollen, which was an encouraging sign, and suggestive that brood may now be present.

We opened the hive, and were pleased to still see a modest number of bees in residence. We’d witnessed a few small orientation flights in front of Rosemary soon after the split, as the capped brood we’d transferred hatched. However, once all remaining brood hatches, orientation flights cease until new brood is produced by a new Queen.

The bees had clearly been consuming some of the honey stores we left with them at the time of the split, but were also storing fresh nectar. However, the first brood frame we encountered, we found our first evidence of chilled brood. This is why I said we under-split Salvia. We obviously didn’t provide enough nurse bees at the outset to cover the amount of brood we transferred to Rosemary.

This was an early season split, and our first split. In hindsight, we should have shaken in more nurse bees to help cover the brood that was transferred during the split. The parent colony has a laying Queen, and can easily produce more nurse bees as needed, but a Queenless split has to make do with whatever population the beekeeper gives them at the time of the split, either as adult bees, or soon-to-emerge capped brood. Rosemary wouldn’t be able to produce any new bees on her own for at least 5-6 weeks (16 days to make the Queen + time for mating flight and egg laying + 20 days until the new workers hatch). It’s a balance transferring in enough capped brood to see them through, and providing enough existing bees to care for the brood until they hatch. With the Lavender split above, we were much more aggressive, to ensure there are enough bees to keep the entire brood nest warm.

We continued to work our way through the hive, trying to be efficient, and as minimally disruptive as possible. A number of the remaining frames were empty, and we were getting quite concerned. However, just as we were contemplating splitting Salvia for a second time, we finally found larvae!

These larvae are approximately 7-8 days old, and if we reopened the hive today, this brood should now be capped.

Because these cells weren’t capped at the time of our inspection, it’s difficult to say for certain whether these larvae are destined to be drones or workers, and the distinction is important.

Capped worker brood is flat (yellow arrow); capped drone brood is domed (red arrow). Worker brood can only be produced by a laying Queen.

If it’s worker brood, that’s confirmation we have a laying mated Queen, as only she can produce worker brood. If it’s drone brood, this colony may still be Queenless, and the brood being produced is the result of an unmated laying worker.

Clues the colony may have a laying worker are that laying workers tend to scatter brood through the hive haphazardly, not together in a central location. The pattern in this hive was nice and even, so that was encouraging.

We did find one anomaly though. Multiple eggs in a single cell.

The lighting isn't ideal, but if you look closely (click to enlarge image), the arrow is pointing to a cell that contains TWO eggs

Multiple eggs in one cell can occur either due to a new Queen who is still learning the ropes, or a laying worker. New Queens usually don’t lay more than two eggs per cell, but laying workers may lay 3 or more eggs per cell.

Another clue to a laying worker is they often lay eggs on the side wall of the cells, not on the cell floor. This is because workers have shorter abdomens than Queens, which aren’t long enough to reach the cell floor.

Here however, we have only a single egg in a cell. All the eggs we observed were laid on the floor, not on the cell walls

If the colony has a laying worker, the only practical solution will be to shake the bees out, as a laying worker colony usually won’t accept a new Queen, even if one is introduced.

New Queens laying extra eggs in a cell usually stop in a few days with a little experience. We were a little surprised to see day 8 larvae, and still find two eggs being laid in a cell, but a few laying errors can still be forgiven at this early stage, so we’re not too concerned. We’ll have to wait and see how the brood looks next time.

Our instinct is that these larvae will prove to be workers, not drones. We noted the frame position of the brood so we can quickly recheck the hive next weekend. We’ll be looking for smooth flat cappings over the cells, as confirmation that we do indeed have a laying Queen. Fingers crossed!

——————————–

Although we lost two colonies over winter, our apiary is now back to four colonies. We’re crossing our fingers that Rosemary will prove to have a well-mated Queen, and that Chamomile will soon be a thriving colony. In the meantime, if you keep bees, the second annual National Winter Loss and Management Surveys are available between March 30th and April 20th, 2012. Participation is entirely voluntary, but the data you provide about the health of your hives, and management practices, may help researchers to better understand winter colony losses, and help other beekeepers to better manage their own hives.

If you’re interested in the results of the 2010-2011 survey, they were recently published here. (PDF)

Very timely post! We did a split a few weeks ago and checked on them this past weekend. I was about to send you an email with questions but you answered all of them here! Thanks!

Glad my ramblings were useful 😉 Hope your split is doing well!

Clare as always I am fascinated…my head is swimming with all the new info…I love that you have split the hives and you may be back to 4 full functioning hives…fabulous images and info as usual!

If I knew how much I would learn about bees two years ago, I think my brain might have had a melt down. These creatures are endlessly fascinating to me, probably in part because they always seem to have something new to teach me!

Hi Clare,

Great update on your Bees; I do love reading these posts with such interesting information on keeping and maintaining their hives 🙂

Thanks Liz. I’m definitely not a hand’s off beekeeper. I just need to get better about being able to see what I’m photographing through my veil 😛

That is so strange, I also have Lavender and Rosemary hives, named after our queens.

So you do! I did find that naming our hives has made it much easier to keep track of who is who 😉 It just seems to make sense to name garden hives after garden plants!

Ouch! Hope your husband’s head is fine. What a surprise that must have been. I am always amazed how much there is to know about keeping bees. It really gives me great respect for anyone that does it. I hope all four of your colonies thrive.

His head was a little sore the first day, now it mostly itches 😉 We definitely weren’t expecting an outright assault so quickly. We always light the smoker before approaching the hives, but this bee found us regardless! Can’t blame her though, in the spring, during swarm season, the hives are in flux, and I’m sure that puts the bees somewhat on edge, especially when the colonies are as large as Salvia and Lavender have been.

Good luck! I’m looking forward to your posts to see how the bees do this season.

I’m hoping this year, with the wimpy Italian bees gone from the apiary, that we can report on their rip-roaring success…but we’ll have to wait and see 😉

Clare,

Sorry to hear your bees were testy and attacked before even smoking them. Glad things are progressing. Thanks for the advice on my small swarm. Right now Tulip Poplar is starting and it’ll be going for at least 6 weeks. This is our areas honey crop, the bees will be very busy in the tops of the trees, poplar grows everywhere here.

I expect your small swarm will do great. It’s still early in the season. Last year, I remember looking at our blob of bees, and was almost certain there weren’t enough to make it. Now, by March 30, that same colony was 5 boxes deep! That’s what I love about bees, they never cease to amaze me 🙂

It is all very overwhelming to me but fascinating at the same time. I enjoy all your photos and video. You are an excellent teacher!

Thanks Karin. It can be a lot to absorb, especially if you haven’t kept bees. Even for beekeepers it’s a lot to take in, and understand. Bees, and bee dynamics, although they seem simple on the surface, are actually quite complicated!

Very interesting post. I’d love to do a honey tasting sometime so I can taste the difference in honey created from different flowers.

Honey tastings are fun. Some beekeepers will keep all honey from each hive separate, even if it’s taken at the same time of year. Different bees have different preferences for flowers, so it’s always interesting to compare honey from adjacent hives. Sometimes the flavor and color can be very different!

Keeping bees seems like daunting work for me, as for now I am still try to learn how to garden :).

There is a learning curve when it comes to beekeeping, that seems quite steep at first. As we go into our second year of beekeeping though, it seems much easier this year. Just as with gardening, there are certain things that need to happen in the apiary at certain times of year.

There’s always so much to learn when I come to read your bee posts Clare. Hoping that you have a Queen in there and I can’t wait for the next episode to read how the newly split hive is functioning. I never realised how much effort and knowledge is needed to have a successful apiary.

I’m really crossing my fingers for good brood in Rosemary this weekend! It will be good to have four thriving colonies in the apiary again.

I always can’t believe how absorbed I get by the stories about the bees. Fascinating all around. I hope it will all work out.

They’re quite fascinating creatures, and I think most of us just don’t think about the day to day life of a bee. I certainly didn’t until I became a beekeeper. It’s remarkable how they all function together as a colony.

How wonderfully informative – I am fascinated on how you split hives! Thank you for this! So beautifully photographed as well. We all might become pro bee keepers yet!

It’s something now, in hindsight, that I wish we’d done much sooner. I really enjoy beekeeping, even if the bees are a challenge to photograph! 😉

Interesting to read about your hive split- I just tried my hand at splitting two of our hives last week for the first time. One with several queen cups and one with young larva I was hoping the workers would turn into queens. Just checked, and indeed, the queen-less hive has made several queen cups and capped them. Woot! Having tried to get good pictures on my hive checks, I am so impressed by how good your pictures turn out!

Yay! Capped Queen cells is a great sign. There are plenty of drones around at the moment, and if the weather holds, your new Queens should do well. Hopefully within a few weeks you’ll have lots of new healthy brood.

Pictures are tricky, especially shooting through a veil. Our hive stand is near a large oak and Ceanothus, both of which tend to throw shadows, making it even more difficult to get the lighting right. Sometimes I just hold the shutter release down, and cross my fingers 😛 Unfortunately some of the egg shots didn’t come out as bright as I’d have liked this time. I’ll have to tweak the camera settings when we peek at the brood this weekend.

You are so careful and organized with your bees no wonder they are thriving. Our beekeeper totally dropped the ball and all the bees died. He never even collected the honey last fall. We are looking for someone else who might want to have hives here.