It’s no secret that Curbstone Valley is home to a host of species of fungi from fall through spring, and fall means it’s the start of the season. Amanita season that is.

The welfare of all the animals on the farm is our top priority, including our pets, and while most of the fungi growing here are relatively innocuous, including some species of Amanita, there’s one potentially deadly species that’s made its presence very well known on the farm this year.

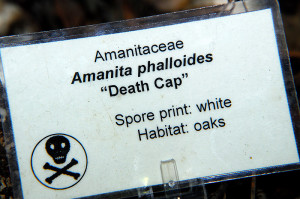

This beautiful mushroom, at first glance, may look benign, but it’s one of the most highly toxic mushroom species in the world, and responsible for the vast majority of fatal mushroom poisonings. This is Amanita phalloides, also aptly known as the Death Cap.

Although we, as adults, know to leave mushrooms alone that can potentially harm us, accidental ingestion can occur if you have children, or pets. Whether or not you’re a mushroom hunter, this is one species of fungi that you need to learn to identify. You don’t even have to go to the woods to find them, as Death caps have been known to grow in some California gardens.

To those not familiar with this mushroom, Amanita phalloides is a relatively unassuming species, however, once you’ve seen one, they’re actually quite easy to identify.

Amanita phalloides native range was once restricted to Europe, but this species has proven to be highly adaptable, and now has a near global distribution. They are particularly abundant around the San Francisco Bay Area, and along the Central Coast, during warm wet winters.

In California Amanita phalloides has a preference for growing underneath our ubiquitous oaks. Due to our persistent coastal fog in the summer months, it can be found year around, but becomes more common during our rainy season, from early winter, through spring. Due to some early October rains, this season we found our first Death Caps on the farm by mid-November.

Field Identification

Like the majority of fungi we find growing here, this is a gilled species, an agaric.

The Death Cap can be variable in size, and in color. The cap ranges anywhere from 3-15 cm. Initially the cap is convex, becoming more plane with age.

The gills are white, and may or may not be visible, depending on the stage of development. Amanita phalloides has a universal veil that conceals the gills when young.

The cap color may appear white due to the veil in very young specimens, but at maturity the cap is generally a dull yellowish-brown, and when moist the surface may appear slightly viscid.

As the fungus matures, this veil breaks away, gradually revealing the gills beneath the cap. A fragment of the veil typically persists at maturity as a white annulus, or collar, encircling the stem. Note however, the annulus may be lost as the mushroom matures, so don’t rely on its presence for identification.

As the veil breaks away, a persistent remnant, called the annulus, surrounds the stem just beneath the cap

Compared with most other Amanitas we’ve seen growing here, one of the most notable features is that the cap is generally smooth. Amanita pantherina, and A. muscaria both tend to have a comparatively rough surface due to persistent veil fragments, even at maturity.

The stipe of Amanita phalloides is white, and solid, not hollow. The stem is typically taller than the cap is wide, ranging from 5-20 cm, and up to 3 cm thick.

Carefully excavating around most Amanita species, one identifying feature is the stem terminates underground at a sac-like volva or ‘egg’.

In this species, the volva is relatively fragile, and easily damaged.

This is a different species, but note the hallmark of Amanitas, usually beneath the soil, is an egg-like structure called the Volva

Accidental Exposures

Although mushroom poisonings are relatively rare, and some species cause little more than indigestion, ingesting Amanita phalloides can be potentially fatal, and this species is responsible for the vast majority of poisonings reported in both humans, and dogs [1].

Occasionally, mistaken identity results in accidental exposure. People used to hunting for mushrooms outside of California may not have encountered Amanita phalloides previously. [2]

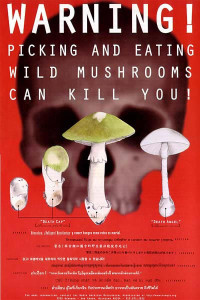

These warning posters were printed in multiple languages to educate the public about Amanita phalloides

These mushrooms, not that I’m going to try them, are reportedly not unpleasant to the taste. If they were, it’s unlikely that Amanita poisoning would occur even with the frequency it does. As such, pets and children are especially vulnerable, as they may not find these mushrooms distasteful.

Here we’re most concerned about our dogs. If you’ve ever been owned by a dog that has a proclivity for investigating the world with its mouth, as is true of most puppies, snuffling up anything new in their environment, you know how quickly they can ingest something, sight unseen. We have such a dog, and although she’s not as bad as she was when she was a puppy, she still can snarf something down before we know what she’s eaten.

Sure, she looks cute and innocent, but for 2 years it was a full time job pulling everything from leaves and twigs, to electrical cords, out of her mouth!

As such, it’s imperative that we’re aware of what’s in her environment, to prevent her from accidentally consuming something toxic. Trust me, if anything around here would accidentally ingest a poisonous mushroom, it’s her!

To avoid exposure, the simplest solution for us is to remove these mushrooms as we find them around the property, and safely dispose of them. If you see mushrooms growing in your own yard, take the time to inspect them. If concerned, remove them. If walking with dogs or children in wild-land areas keep them close by so you can keep a watchful eye on them.

Toxicity and Clinical Signs

Amanita phalloides contains numerous toxic compounds, that fall into two primary classes of toxins, amatoxins and phallotoxins. The primary toxins that result in illness are α-amanitin and β-amanitin, but other toxic proteins are also present in Death Caps [3].

Ingestion of Amanita phalloides typically results in vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain, within 6-24 hours of ingestion. Symptoms can be initially severe, but after 24 hours, they may appear to resolve briefly. However, despite this apparent resolution in clinical signs, organ damage continues, and typically within three to four days of ingestion, patients will exhibit signs of hepatic, and renal failure.

If you suspect ingestion, either by a child, or a family pet, you must seek medical attention immediately. If you have evidence of mushroom ingestion, take it with you!

Not all mushroom intoxication is the result of Amanita phalloides [4, 5], and not all Amanitas are poisonous. If possible, taking a sample of the mushroom with you, large or small, can facilitate identification of the species in question, and aid in diagnosis, and treatment. In an emergency, the North American Mycological Association has a team of volunteers that can assist with identification.

You'll never identify these fragments of mushroom, but an expert may still be able to determine the species

Obviously, in the case of Amanita phalloides, exposure prevention is key. Proactively teach children about poison prevention. Inspect, and remove suspicious fungi from lawns and gardens where pets and children play. Most importantly, don’t forage for mushrooms unless you absolutely know what you’re doing, and remember that just because you may be comfortable foraging for mushrooms growing in your region, it doesn’t mean that a similar appearing species growing elsewhere is necessarily safe to consume. Erroneous identification is a significant cause of mushroom poisoning.

Here we exercise an abundance of caution, so when it comes to fungi for the kitchen, we choose to source cultivated species from the Farmer’s Markets. During our Mushroom Monday walks, we only hunt mushrooms with a camera, and to prevent accidental exposure, any Amanita phalloides we encounter here are systematically removed, and disposed of, for the safety of both our animals, and visitors to the farm.

Can you identify a Death Cap?

American Association of Poison Control Centers: 1 (800) 222-1222

National Animal Poison Control: 1 (888) 426-4435

————————

[1] Schonwald S, Mushrooms. In: Dart RC, ed. Medical toxicology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2004;1719-1735.

[2] SFgate.com January 6, 2009. Deadly mushrooms send 3 to UCSF hospital.

[3] Stasyk T. et al. A new highly toxic protein isolated from the death cap Amanita phalloides is an L-amino acid oxidase. Federation of European Biochemical Societies Journal. 2010 Mar;277(5):1260-9. Epub 2010 Feb 1.

[4] Naude TW, Berry WL. Suspected poisoning of puppies by the mushroom Amanita pantherina. J S Afr Vet Assoc

1997; 68:154-158.

[5] Ridgway RL. Mushroom (Amanita pantherina) poisoning. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1978; 172:681-682.

Clare, this is very interesting and good reading!

On another topic – your calendar arrived here on Friday in Cape Town, South Africa! Its stunning! I love it!

Glad the calendar arrived Christine! So happy you like it, enjoy! 🙂

Good warning. It makes sense that someone that has never heard or seen these before might be poisoned accidentally. I’m skeptical of all mushrooms in the wild, and I’m almost certain (but am no expert) that these grow around here. I hadn’t thought about dogs eating them. Good point.

Dogs do eat them, and there have been a few recent cases in the Bay Area. I think although we know we’d leave them alone, we forget sometimes about our inquisitive furry friends!

Fascinating mushroom and pretty for being so sinister…glad to know what it looks like, but I just enjoy them with pictures…I m too afraid of poisoning myself to ever experiment with mushrooms from the yard…

You and me both, wild mushrooms deserve a lot of cautious respect. This one is remarkably beautiful though, for being so deadly!

Even after reading this post with all that information I still wouldn’t be sure about identifying this mushroom. As I looked at the photos I thought it looked similar to ones I have seen here but likely are not the same thing. I too leave mushroom picking up to others and purchase them from the store. I love a tasty mushroom but in my own yard I’ll settle for photos.

A few of these photos were taken at a our local Fungus Fair last January (the ones with the descriptive tags). It’s difficult to provide conclusive ID tips in photographs. Fungus fairs and festivals though are a great way to see things like this in person, and familiarize yourself with other toxic species that might be common in your area. After seeing them in person a few times, I’m now pretty confident IDing one in the field. If it’s growing here, and I’m not sure, I get rid of it, just to be safe. 😉

I am like Marguerite, I too would have a hard time identifying this mushroom even though I have heard of Death Caps before. I never pick mushrooms anyway, but your point to note the danger for the pets is a good one. I had a Lab at one time that ate just about anything, farm chickens included, and luckily he lived to be 17 years old, even with farmers buckshot in his rear.

That’s the trouble with our young dog…too much Lab! I’ve never had a dog put so many foreign objects in her mouth. It’s exhausting! We’re just determined that these mushrooms won’t be something she’ll be sampling any time soon 😉

Great post, very informative. Don’t know if these grow in Ireland but it’s as well to be aware of them. Hope you and yours have a wonderful Christmas.

According to what I’ve been reading, this species is actually relatively common in Britain and Ireland. Although I’m not sure how common they are in gardens there. I think our warm weather, and coastal climate, make them extra happy here! 😛

Gosh, that’s a toughie to ID. I’ll be keeping my eyes peeled! Thanks for this valuable info – will be put to good use, to be sure.

There’s a reasonable chance you have them up where you are too, although you do tend to be drier than us. Down in the valley here we seem to be fungus heaven 😉

‘Death Cap’? Yikes!

Just say no to mushrooms, kids. O_O

Exactly! That ‘just say no’ clause should apply to most of us adults too 😉

This is an excellent educational post!

Although I have never found death cap mushrooms in L.B., we do see many other wild mushroom varieties growing in garden beds and lawns. I love mushrooms and photograph them whenever I find them. However, many years ago, my 2+ year old daughter found a wild mushroom in the mulch in our backyard and ate it before we realized what happened. It was not a pretty trip to the ER. It was even more frustrating when the hospital staff weren’t sure how to deal with the emergency, despite having a sample and us having arrived within 15 minutes of ingestion.

I like Kyna’s philosophy of “Just say No to wild mushrooms.” Because of my daughter’s experience, I will probably never go mushroom hunting. I am glad you posted this.

Thanks,

Leanne

Wow, thanks for such an informative post – am definitely passing this along. Just yesterday I was in my garden and noticed many different mushrooms that seem to have popped up overnight, and with a new dog I need to be really careful as I’m not sure if he’ll sample them or not. Since I’m not an expert in ID’ing mushrooms, I think I’ll just remove them all – better safe than sorry!