The weather this spring has been a little off, and less than ideal for bees. The temperatures have been below normal, days often overcast, breezy, and late season rains have thrown hives all over northern California for a loop in recent weeks.

We attended an all day beekeeping class this weekend, and at the beginning of the class it was mentioned that a number of commercial beekeepers this spring in northern and central California, after a failed black sage and citrus honey crop this year, have been forced to feed their bees. Even those that don’t routinely feed their bees found themselves suddenly scrambling to provide their colonies with emergency nutrition, or risk losing their bees to starvation.

Beekeepers don’t expect to lose hives in June, but some beekeepers apparently reported losing hives during the recent foul weather. It’s not that the weather was especially bad per se, but when the weather conspires against honey bee foraging during the peak of brood-rearing season, colonies can suddenly find themselves short on resources. This can hit strong colonies, with large amounts of brood, especially hard. This is exactly what we observed in our Salvia hive two weeks ago, where despite the apparent strength of the hive both in numbers of bees, and amount of brood, the larder stores we’re almost empty. The consequence was significantly increased defensiveness in our apiary.

There’s some degree of controversy in regards to feeding honey bee colonies, especially in natural beekeeping circles. Some won’t feed regardless, opting for the thrive-or-die approach to keeping bees. However, from our perspective, if a dog couldn’t reach its food dish, would we just watch and let it starve? Or would we place the food where the dog could reach it? We don’t want to feed our bees excessively, but in part as a result of human incursions, bees don’t live in a perfect world, and as beekeepers we’d rather be proactive, and assist our bees if necessary, rather than sit back and watch them starve.

Our decision to resume feeding all of our hives in the hopes of decreasing the defensiveness of our colonies certainly seems to have helped. Yesterday’s inspection was much more civil, the bees much calmer, and there was significantly less need of the smoker. Peace and quiet seems to have been restored to our apiary, at least for now.

We took a quick cursory peek in all the hives yesterday, primarily to determine if any of the hives needed additional space for brood-rearing, or food stores. We were encouraged to find more nectar and honey stores, but we also found something very interesting in both swarm colonies…

Queen Cups

The Salvia hive was populated from the primary swarm we captured in March that contained a fertile Queen. The Lavender hive was an afterswarm from the same colony containing a virgin queen. By the time the Lavender Queen was finally laying eggs, the Salvia hive had a one month head start on brood rearing.

The difference is that Salvia is now twice as large as the Lavender hive. What was interesting though, was up until now, we haven’t seen any Queen cups in either hive. As Queens, especially from primary swarms, are often superseded within weeks of establishing new colonies after swarming, we expected we may see some Queen cups soon…but yesterday, we found them in BOTH of the swarm colony hives.

In the last two weeks, for reasons known only to the bees, both colonies decided to start making Queen cups at the bottom of the frames of comb. Conventional wisdom is that cups on the bottom of a frame are destined to be ‘swarm cells’, Queen cells built in preparation for swarming, and that Queen cups further up the frame are fated to be ‘supersedure cells’, cells made in preparation for replacing an aged, ill, or injured Queen [1].

This Queen cup, in a friend's hive, was built higher up the face of the frame, and is often called a 'supersedure cell'

In reality though, any Queen cup in a hive can be used for either swarming or supersedure.

The presence of Queen cups in a hive however isn’t necessarily cause for alarm. Weak hives don’t swarm, so the presence of cups suggests that the colony is relatively strong, which is good news. Some races of bees are renowned for maintaining Queen cups in the hive, as a sort of ‘hive furniture’, where they will use them if a need arises. The cups may be there one week, and deconstructed the next.

If however the Queen has laid eggs in these cups, and there are developing larvae present, or the cups have been capped (turning them from cups to cells), a new Queen is imminent, setting the wheels in motion for the supersedure or swarm.

At the moment it’s unclear if our swarm colonies are simply rampant cup-builders, or if they’re preparing for a supersedure or swarm. Regardless, the first thing to check as beekeepers is whether or not the Queen has room to continue laying eggs.

Two weeks ago, empty frames abounded in both of these hives. Now though, as a consequence of feeding, and the improved foraging weather, the bees are storing honey and nectar again. In Salvia it seemed clear that they were filling every nook and cranny possible with nectar and honey, although pollen reserves are still quite low.

The Lavender hive was similar, and the outside frame had some especially tall comb built where there was some capped honey.

They’ve also continued to expand the brood nest. As such they had succeeded in filling the combs with brood, nectar, and honey, all the way to the outside frames on the upper hive body. Generally they ignore the outside frames, but yesterday they were crammed full.

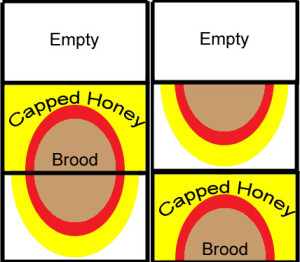

The brood nest is somewhat football-shaped, across multiple hive bodies, and constructed in rings. The outer ring is comprised of honey stores. The center ring is usually pollen, and the inner ring, or core of the nest contains the eggs, larva and pupa that will become new bees. A problem arises if the outer ring of honey becomes capped all the way across the top of the brood nest, a condition known as being ‘honey-bound’. If that happens the honey acts as a barrier. The Queen won’t cross a capped honey band to lay eggs, and the worker bees themselves are reluctant to move past it. This is why it’s important during nectar flows to ensure you’re staying ahead of the bees by adding supers.

The clue something wasn’t quite right was that even though there was an entire empty hive body on top of the swarm colonies for the last two weeks, the bees had barely touched it. They’d built out the box below all the way to the outside frames, but they hadn’t moved up to the empty supers we left them last time.

After removing the top cover, a few bees were seen on the screened inner cover in both Lavender and Salvia, but on inspection, the frames in the upper hive body were still undrawn foundation

What was interesting was the complete absence of Queen cups in either of our package colonies, Chamomile and Rosemary, both of whom are moving up into the new supers we left them last time, and drawing comb. Our suspicion is these potential ‘swarm cells’ in the swarm colonies are a result of crowding.

There are various methods employed to encourage the bees to utilize space in new boxes. Bottom supering, or placing a new hive body below the upper brood box is one method. By dividing the brood nest, the bees are motivated to use the new frames quickly. However, this should be done using frames of drawn empty comb, of which we have none. Our choices were limited because our new frames are all undrawn foundation.

Bees tend to draw comb from foundation best at the top of the hive. So instead of bottom supering, another method is to simply reverse the two uppermost brood boxes. By moving the top brood box down below, the band of honey at the top of the brood nest ends up in the middle of the brood area, breaking the honey-bound condition, and clearing a path to the empty super above.

Three hive bodies with a normal brood nest configuration (left), and after swapping hive bodies (right)

The bees don’t want the honey in the center of the brood nest, so they are strongly motivated to move the honey back up to the top of the hive. With a new empty super on top, the hive is now larger, and the bees should now draw new comb from the foundation, and relocate their honey stores to the previously empty upper hive body. This frees up space in the center of the brood nest for egg laying again, and the bees are subsequently less crowded.

This is what we did yesterday with the Lavender hive to encourage the bees to move up. Leaving them scrunched together would increase their impetus to swarm.

For the Saliva hive our approach was a little different.

These bees were just starting to draw comb in the upper box, but barely. Our last inspection of this hive was quite invasive, and we didn’t want to disrupt the bees that much again at the moment, if it wasn’t necessary. Instead we took an outer frame of honey, and two frames with mostly honey and very scant brood from the edge of the brood nest, and placed it in the center of the relatively untouched upper hive body, making sure any brood was positioned above the brood below. This is not something we’d do in cool weather, and wouldn’t move brood in a weak hive, like our Chamomile hive, as it’s imperative that there are sufficent nurse bees to tend and cover the brood.

In this case though the weather is warm, and the population in this hive is robust, to say the least.

We returned some empty frames to the box where we’d removed the full frames to help create a passage bewtween hive bodies on one side. By placing brood in the new upper hive body, the bees will need to move up to tend the brood, and in turn should be more motivated to draw the new comb in that box. We’ll have to wait and see how well this approach works. With as many Queen cups as were in this hive (we stopped counting after a dozen), we’ll need to keep a close eye on this colony over the next couple of weeks, and can make adjustments as necessary. If any of the Queen cups are capped in subsequent inspections though, we may find ourselves doing an impromptu split!

As for feeding, now that the sun is shining, and the weather is warming up, we thought we could stop. However, the weather has affected the bloom cycles of a number of plants this year, and at the moment there is little in bloom here beyond the monkey flowers, which the bees don’t frequent much, and the California Buckeye (Aesculus californica), which is in peak bloom now, and although relatively harmless to native pollinators, its nectar is toxic to European honey bees, and humans. [2] I found a few bees foraging on these flowers this morning, perhaps bees from our own colonies?

Don't be fooled, these beautiful flowers, from the California Buckeye, can cause significant harm to weak bee colonies

We’ll cover plants that are toxic to bees in a later post. However, during our class this weekend, the advice we were given, which makes a lot of sense, was to offer an alternate nectar source during peak Aesculus bloom to help dilute the effects of the toxin in our hives. Once the Aesculus flowers fade, which are adjacent to our property, the supplemental feed can be removed.

——————-

[1] Root, Amos Ives. 2006. The ABC & XYZ of Bee Culture. 41st Ed. p 792

[2] United States Forest Service: Species Profile – Aesculus californica

Clever re-arranging. For some reason the process reminded me of the four color map theorem, which states that no more than four colors are required to color the regions of a map in a way that no two adjacent regions have the same color. I haven’t thought of that one in a long, long time.

I’m not surprised to hear that beekeepers have had to do supplemental feeding this year – it has been such a strange spring. In retrospect it was good that your bees’ increased aggressiveness alerted you to a problem, even tho’ Mr C.V. might not have as benign a view.

I agree, a bee sting or two was worth it to prompt us to inspect those hives, and notice how low their food reserves were. I think even Mr. CV would concur. It has been a strange spring this year. For as much rain as we’ve had, we seem to have relatively little in bloom at the moment.

Clare,

Really good post! You have learned so much about bees. Our bees looked to perhaps had a hatching yesterday. Lots of bees flying 5-6 foot over the hive, getting bearings perhaps. We have had our bees a month tomorrow. Next inspection in a week or so. Yes we are feeding right now a pint of syrup a day, at first it was a quart. As far as I know we do not have any toxic flowers here.

It’s funny, the more I learn about the bees, the less I feel I really know. As an organism, they’re perhaps one of the most studied species on earth, and yet we still have so many questions about them.

I expect your decrease in syrup consumption was either that they’d drawn out the comb they needed to start (ours seem to spike consumption when we first put in new frames), or you have better choices of forage outside the hive. Generally we’re told by other beekeepers that they won’t take it, if they don’t need it. Our two swarm hives are downing a quart a day right now, but we’re not seeing much forage around at the moment, except for the Aesculus!

Clare, I’m enjoying your bee tales at least as much as last year’s chicken tales. I love learning new things — and since bee-keeping is a subject about which I knew almost nothing, I’m enjoying a gratifyingly steep learning curve!

Your weather sounds like ours — unseasonably wet and cool. I feel as though my garden is in a state of suspended animation, with all kinds of buds just waiting for a warm sunny day to burst into bloom.

That’s been one of the most fun things about embarking on this journey. I knew very little about bees, just what I was taught as a child, and some minor bee-behavior gleanings from an animal behavior course in college. Like you, I like to keep to my brain busy, and love learning new things, and with bees, there’s a lot to learn! On the outside, an unassuming insect, on closer inspection, especially evaluating the colony as a whole, a phenomenally complex organism!

I will echo Jean’s comment. I too am enjoying your bee adventure and am living vicariously through all that you are doing and writing about. The same with the turkeys and chickens. I love learning about raising all the creatures you have on your farm, I guess because your animals all have a purpose. The farm where I am each day has animals, but they are all sort of like pets. Like what purpose are zebra, koi, and elk? The deer at least provide income. I guess that is why I rarely feature these animals anymore than a passing photo.

Uh oh, if we added a Zebra to our menagerie, then the neighbors would know we’re crazy 😛 Next stop, possibly goats, but with our predation issues here, that won’t be for a while. I do miss having fish though…

It’s nice to have a bee group to go to for advice and support. I imagine you can make good friends there at classes and meetings. I wonder how much salvias you’d have to plant to support your bees?

I’m not sure, and it would probably depend on type. I do see the honeybees on the Salvias, but they seem to prefer the lavender, rosemary, thyme, and cane fruit blossoms. My guess would be we’d have to at least trade in the orchard 😉

Hi CV,

It’s always so interesting reading your blog on Bees, I am sure soon we will all be experts too 🙂

I’m not sure there are truly expert beekeepers, not anymore. All of the maladies affecting bees these days I think leave most beekeepers just trying to do what they can to support their bees, and hoping they survive. We learn as much as we can, and do what we can, and hopefully the bees will better for it.

I agree about helping them – if you are keeping them then you are responsible for their survival in times of real hardship.

I had not realised there were plants toxic to bees so I will look forward to your post.

I happen to have two species of plants that produce nectar that’s toxic to bees in bloom at the moment. Clearly I need to plant more lavender 😉

Wow….I never knew that some plants were toxic to bees. Look forward to your further posting on this.

Unfortunately, the Aesculus californica tree is a native tree, and quite abundant up here. It’s apparently not toxic to all pollinators though, but I’ll elaborate on that in a post soon…

Wow – so much to know about beekeeping! I had no idea you might have to supplement their food, and that some blossoms were toxic! I am amazed at your knowledge.

Food supplementation, especially at certain times of year, seems to make difference in survival for some colonies. A lot depends on where you are. If we were in town, in a more urban area, where everyone had flowers in bloom in their gardens most of the year, it might not be necessary. Here in the woods though, we get a spring flush of bloom, but most of the native plants are done flowering by mid to late July. The difficult part is figuring out when the bees have forage, and when they’re at risk for starvation. It certainly forces one to be aware of the plants in the area, pollen availability (although my allergies usually tell me when pollen abounds), and nectar flows!

Wow I never realised that there was nectar that was toxic to bees Clare! Looking forward to your next installment.

It does seem strange for a plant to potentially poison its pollinators, doesn’t it? 😉

Such a fascinating hobby, isn’t it? I always enjoy reading about others bee experiences. I did an inspection yesterday. At 4 weeks out our package bees have 80% of the frames drawn out, so I am adding a second deep hive body. I’m feeding syrup and pollen patties until the first honey super goes on. They are taking up a little over a pint of syrup a day. Which translates to a lot of sugar!

Sounds like your bees are doing great! One of our packages is strong, one is noticeably weaker. We got so distracted with Queen cups on this inspection with the swarm colonies, we ran out of time to swap the package hives on the hive stand, but hopefully we’ll get that done this weekend.

They do consume a lot of sugar when they’re feeding. I’m making 3-4 quarts a day right now. It’s a good thing sugar comes in 50 lb bags! 😛 Ours are tearing through their pollen patties too, as we seem to have a bit of a pollen dearth since the oak pollen went down.

The weather really does seem to have affected the bees this year. I wondered if the late blooming of many flowers had anything to do with it. We have tons of bumblebees of all different sizes and colors, but still haven’t seen any recent honeybees. I’ll be interested to learn about the toxic flowers, I didn’t realize there was such a thing.

One problem with the weather here, at least from my passive observation in my own garden, is that some of the late storms have simply shortened the bloom time of many plants this spring. Just as they started to bloom, the flowers were knocked off by heavy rain. During less wet springs here I think there’s usually enough other flora in bloom when our Aesculus is in flower, that toxicity is less of a concern.

Clare, I had once considered having bees and I’m absolutely loving this impromptu bee keeping course! Not sure anymore if I would want to take care of bees but regardless this series of posts has been extraordinarily interesting.

Thanks Marguerite. Beekeeping certainly isn’t the hobby it was 20 years ago. Then, the beekeeper was primarily responsible for ensuring the bees had enough room in the hive, and harvesting excess honey if there was too much. Now, it seems we have to be pseudo-experts in parasitology, microbiology, and nutrition, just to help our bees survive each year, and some years, honey is a bonus. It’s more involved than I think even I expected, but fortunately, I love a challenge 😉

I am learning a lot from your blog, however i can’t remember all of them, at least i get some mechanics of bee culture, and the bee organism. I am amazed at the intricacies of it. I have a question, will constant feeding or provision of easy food will not make them lazy? Or i am afraid they will not look for nectars anymore because of the easy food! haha, am i asking a stupid question!!!

There are no stupid questions in beekeeping. I think bees are far too industrious to become lazy. They do more in an hour than I get done all day! 😛

Generally, from what we’ve been told, and observed so far, if there’s good forage available, and the bees don’t need the supplemental feed, they won’t take it.

The Salvia hive previously stopped taking feed, and we removed it. When they ran out of stores though, and we put the feed back, they’ve been consuming a lot! I’d prefer the bees forage on natural sources of food, rather than sugar water and pollen patties. At the moment, as we’re preparing to remove the feed completely from the hives, and don’t want them stock piling sugar water nectar, we’re down to feeding a 30% solution of sugar water.

Once the Aesculus winds down, we’ll take the nectar feeders away from all the hives. We may leave the pollen patties in a little longer though, as there seems to be a real lack of pollen in all our hives at the moment.

I like your approach to assist the bees by feeding them. I think that is a good idea. One day I see myself keeping bees…one day in the future, but not right now…and I am learning lots from your posts.

Fascinating as always — I learn so much by reading your bee posts! Looking forward to the toxic plants post too. I had no idea!

It’s fascinating that we live relatively near one another, and yet our bees’ lives are so different. We’ve never had to feed our bees, but we also live in a much more densely populated, and presumably planted area. I’ve read that urban bees have more access to forage, because the plants in a city skew toward flowers.

I dream about goats, but I think that’s a perverse fantasy on my part. Those little devils would tear my yard to pieces. (I do love ’em.)

It is really interesting to see the growth of “beekeeper jargon” in your posts as you get more into the whole art and science of bee keeping. There is a lot to it and I can see how absorbing that can be. I like language more than bees maybe!! It’ll be a while before I have enough time and free brain cells to take on a new thing – slowly learning the ins and outs of propagation is my limit right now, and slowly slowly learning more about the flora and fauna – very slowly. I am waiting for my term “crickety-things” to diversify into actual species recognition and correct names! I agree that you should help the bees, too. They are not wild life being observed by David Attenborough – they are domesticated animals!

Hi Clare – interesting about the lack of blooms this time of year rather like my garden but challenges the assumption that early summer is a time of plenty. As usual you have piqued curiosity re the poisonous nectar but then as humans move animals out of their native environment it is to be expected that the locale may not always suit.

Laura

p.s. love the flash display of your recent posts on home page and divine queen cup shots

Well, I had only planned on scanning for a few minutes, but I got caught in your wonderful web of natural history.

LOVE this!

Thanks a zillion…have you seen the Oxford Press book on The Quest for the Perfect Hive. it is fascinating.

Pocketful of joy to you,

Sharon Lovejoy Writes from Sunflower House and a Little Green Island