Mr. Curbstone Valley here bringing you this week’s Fowl Friday post, as we take a look at poultry genetics, and how it relates to the various shapes of chicken combs. We never thought much about comb shapes before we increased the variety of chicken breeds on the farm this year. Since we now have two roosters (Frodo and Siegfried), and are considering breeding a few of our own chickens, we decided to look into some of the possible crosses we might get.

Gregor Mendel described in his 1865 paper Experiments on Plant Hybridization his studies of pea plants (Pisum sativum), and this formed the basis of our understanding of genetic inheritance. And while the 145 years since his discoveries have seen many improvements in our understanding of the details of genetics and the true complexities of inheritance, the fundamentals that he described are still useful for understanding the basics of many inherited traits.

One of Mendel’s fundamental observations was that when some traits (flower or seed color, seed shape, etc) were crossed, the offspring were not blended versions of those traits, but instead showed the trait of one of the parents. Then if the offspring were crossed together, the second generation of offspring would show a ratio of approximately 3 of the one variation to 1 of the other. This he reasoned is caused by factors, that we now call genes, and these genes had dominant and recessive versions.

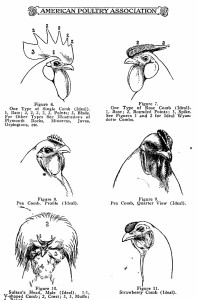

Most of the chicken breeds we have here at Curbstone Valley have Single combs, like Siegfried pictured above, which breeding experiments have shown is recessive to both Pea and Rose-type combs. Most simple genes are inherited in pairs, and each half of a pair of genes is received from each parent. If a bird is pure-bred it is very likely that both copies of the genes controlling comb shape are the same (homozygous), as heterozygous individuals (with mixed pairs of genes) could still breed offspring that don’t match the standard for the breed, and would be removed from the breeding stock.

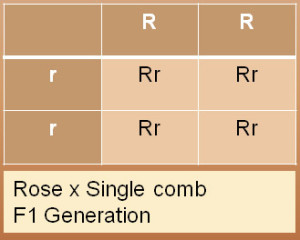

For example, let’s cross a pullet with a Rose comb, like our Golden Laced Wyandottes, with a Single comb chicken like Siegfried. We can refer to the dominant gene (causing the Rose comb) by the capital letter R and the recessive gene (meaning absence of rose comb) with the lower case r. There are three different combinations possible in any individual: RR, Rr, rr. The recessive Single comb, like Siegfrieds, only occurs in individuals with the rr genes, and the dominate trait occurs when either combination RR (homozygous like the pure case) or Rr (heterozygous) are present. Both the Rr and rR are physically indistinguishable (meaning it doesn’t matter if the trait is inherited from the male or female parent) so both can be combined into the same group for breeding purposes, and by convention we call this group Rr. We can refer to all the individuals with Rose combs (either heterozygous Rr or homozygous RR) as R_.

A way to help understand the possible offspring from a cross is by use of a Punnett Square which diagrams all the possible outcomes and helps to calculate the probability of each type of offspring occurring. Let’s start with the Punnett Square for our cross of purebred Rose (RR) with Single comb (rr) cross. The genes contributed by one parent are labeled across the top, and the other parent down the side column. So the Punnett Square for the initial cross would look like what is shown in the first table above. Giving, in what is called the F1 (children of the parents) cross, all the offspring having the same Rr gene combination (all display Rose combs, but are genetically heterozygous, as Rose trumps Single comb expression in the offspring). If a pair of Rose-combed individuals from the F1 generation is then crossed together we get the combinations shown in the second table below.

This is the F2 generation (grandchildren of the parents) and where things get more interesting. We see individuals of the 3 different genetic types in a ratio of 1:2:1 for RR : Rr : rr respectively. The visible comb shapes observed in the chicks would be 3 dominant Rose : 1 recessive Single comb. This unpredictability in the appearance of these offspring is analogous to growing plants from seeds produced from F1 hybrids in the vegetable garden, where the resulting plants may or may not resemble the traits of the parents.

If we continue breeding F3 (great-grandchildren of the parents) and later crosses of individuals that display Rose combs the results will depend on which individuals we select to cross. Of all the Rose comb offspring in the F2 generation one third will breed consistently, because they’re homozygous (both comb genes are identical), but two thirds are mixed (heterozygous) like those in the F1 generation. The way to verify that the individual that you want to breed is homozygous for a dominant gene, like Rose comb, (without access to modern genetic testing) is to breed them with an individual with the visible recessive gene, like Single comb. If the offspring all display the dominant form (Rose) the parent was pure (RR), but if half show the recessive trait (Single) then the individual in question is still heterozygous (Rr) for the trait and further breeding is required to an individual that breeds true (i.e. is homozygous for that trait).

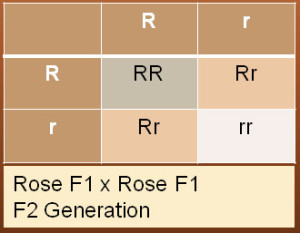

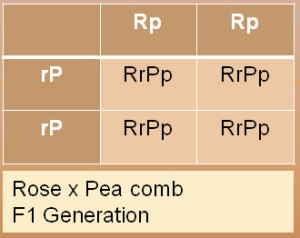

When two or more gene pairs per parent are considered the Punnett Square gets larger as we consider all the combinations of genes that could be contributed by each parent. The gene that controls for Pea comb has been shown to be a separate dominant gene from the Rose comb gene. These two genes together determine the most common comb shapes. So the common combs, and the possible full genotype for these two genes that control them are: Single rrpp, Pea rrP_, Rose R_pp, Walnut or Strawberry R_P_. There seems to be some difference in descriptions for Walnut vs. Strawberry comb shapes, so there may be some other genes involved there as well.

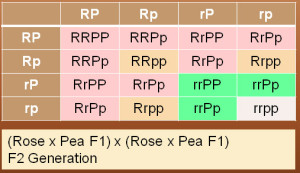

The Brahma, like our rooster Frodo, is a Pea comb breed and our Golden Laced Wyandotte pullets have Rose combs. If we were to breed them (and assume they are both pure homozygous types rrPP, and RRpp) we would likely get the results show in the next Punnett Squares.

The F1 generation (table abbreviated because it is all the same) would get a dominant Rose R and recessive non-pea p from Frodo, and a non-Rose r with dominant Pea P from the hen, yielding identical RrPp offspring. These F1 individuals would all have Walnut type combs, but would be heterozygous.

Breeding a rooster and hen from this F1 cross would give the somewhat more complicated F2 generation with all the combinations for these two genes possible. If enough chicks were bred from this pairing they should show a distribution of comb types with a ratio of 9 Walnut : 3 Rose : 3 Pea : 1 Single.

This of course is simplified for the purpose of these examples, but there are lots of other genetic factors that control the variation of the comb shape and size. Just considering these two genes can create an interesting assortment of possibilities. In a future post we’ll try to look at some more complex gene combinations that affect feather coloring traits in chickens.

I think I might have to read this post a few times. 🙂

thank you Mr CV for the most well written piece on genetic inheritance I’ve ever read in that I can actually understand it and have learnt a lot from this. And also thanks for encouraging Clare to keep a blog – so many of us love her posts and all your wildflowers and wild fowl!

Laura

Great information on chicken combs! I think I shall never look at a chicken the same again. I will always be trying to identify that comb. Your chicken portraits are so beautiful! When I was a girl, my grandpa had chickens, but I hate to admit, I never really looked into their faces so deeply. So much personality!

Dear Mr CV, No wonder people can study genetics for a lifetime!! There is always ‘pot luck’ and the suck it and see approaches…. I think that these are the ones I should use!!

I loved taking genetics in school. Probably the only math I ever enjoyed 🙂

That was a pretty cool lesson!

Are any of these types of comb considered more or less advantageous for your flock?

Are there genetic traits you hope to encourage?

(And, hello Mister Curbstone! Nice to hear from you on this very interesting blog.)

In cold climates the large single combs can be susceptible to frost damage, so the smaller pea and rose combs can be beneficial. In our climate it won’t matter much.

I really enjoyed reading your post, as it brought back fond memories of Gregor Mendel and Punnett Squares from my bio courses back in the day. I’m also very curious, along the lines of what Lisa asked before me, as to what, if any, particular comb type(s) you would like to achieve in breeding? Btw, Frodo is quite the handsome fellow!

Thankyou Mr CV for a most informative post – you remind me of my biology teacher who used to use charts like this in his genetics lessons. Are there any problems with interbreeding with some of these varieties of chicken?

A little clone of Frodo would be nice – I think he needs someone that looks just like him.

There shouldn’t be any problem cross breeding these chickens, although the only ‘standard breed’ we could currently get would be the Partridge Plymouth Rocks (Siegfried and matching pullets). The rest of our flock would be crosses. We may not get much that looks like a Dark Brahma (like Frodo) unless we add a Dark Brahma hen to the flock.

Blink blink.

So will Frodo get to mate? Or is he to be left out in the cold because of his strange pea comb? That’s pretty much what I’m wondering now… 😉

Just out of curiosity I’d like to see what the walnut/strawberry comb looks like from Frodo crossed with the GLW. On the other hand the GLW pullets tend to have a lot of attitude and Frodo so far hasn’t done a good job of sticking up for himself… We’ll have to wait and see how well he can defend himself when he gets closer to full maturity (which may be 14 months because of his breed) to see what hens might be able to move in with him.

This is VERY informative and quite interesting. I must say that I never really thought about this subject before, but I’m intriged. I smiled when I saw the Punnet Square…something I haven’t seen since my school days…I’m sure I’ll see it soon again as my son enters middle school this year.

The head on shot of Frodo is adorable!

Dear CV – having just had to study plant genetics for an exam, I was amused to find the Mendelian principles taken from the peas and used on the combs. Very interesting indeed.

This reminds me of my Genetics 101 class. Interesting info on how it applies to chickens.