Late last autumn we noticed some interesting heart-shaped leaves pushing through the soil near one of our redwood groves while we were installing the deer fence. At first glance it seemed this plant might be wild ginger (Asarum caudatum), but on closer inspection the heart-shaped leaf margins seemed too scalloped to be Asarum.

After some inconclusive sleuthing, we needed some help identifying our mystery plant. I thought it might be a wild violet of some sort based on leaf shape, but couldn’t be sure. I had recently met Christine from Idora Design through the garden blogging community known as Blotanical, and knew she was much more well versed in California native plants than myself. I emailed Christine some photographs of the leaves for her opinion, fully recognizing that a definitive identification might not be possible until the plant bloomed.

Christine’s best guess was that the leaves were most likely those of Viola ocellata, also known as Western Heart’s Ease, Two-eyed Violet, or Pinto Violet, but that we wouldn’t know for certain until the flowers emerged. Impatiently, we’ve been waiting…and waiting…and WAITING for this plant to bloom ever since! It turns out Christine was right, we do indeed have Viola ocellata growing here, as evidenced by the first blooms this spring! Thank you Christine!

Viola ocellata is an herbaceous perennial, native only to California and extreme southwestern Oregon, found growing from Monterey county northward, primarily in mixed coastal redwood forests between 500-3000 feet in elevation. Jepson’s A Flora of California specifically notes that Viola ocellata is known to grow in the Glenwood region of the Santa Cruz Mountains.

Growing from five to twelve inches tall, the small one-inch white flowers usually emerge from March through June. It seems to be blooming a little early this year, no doubt due to our warm wet winter. When viewed from the front, the base of each petal is yellow, collectively forming a yellow throat at the center of the flower. The two lower lateral petals are also usually spotted with purple. The lowest petal of Viola ocellata is striated with purple, and these striae are thought to be ‘nectar guides’, UV markings that attract pollinators to the nectar source at the base of the flower.

The flower of Viola ocellata consisting of 5 white petals, with yellow bases, forming the colored throat of the flower

When the flowers are viewed from behind, the two upper petals have purple ‘eye-spots’, hence the name “Two-Eyed Violet”.

The eye-spots on the dorsal-most petals are responsible for newly emerging flower buds appearing burgundy to purple in color.

As the flower unfurls, it is clear the purple color of the buds is due to the eye-spots on the petals

This plant seems very prolific here, now that we know what we’re looking for, forming numerous colonies near the redwood grove below the vegetable gardens.

Some of the leaves, as they begin to senesce, turn a beautiful shade of burgundy red.

Unfortunately, detailed references for this plant seem rather limited. There are references that suggest Viola ocellata is a known host plant for the Pacific Fritillary butterfly (Boloria epithore), often sighted here in late spring.

Although Native Americans have been known to use many species of Viola either as food or medicine, I haven’t been able to find any ethnobotanical data relating to the specific use of Viola ocellata.

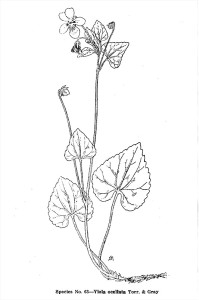

One early reference regarding Viola ocellata is found in the Violets of North America by Ezra Brainerd, published in 1921, which includes the line-drawing below.

The line-drawing is based on a herbarium specimen from Mount Tamalpias, collected June 6, 1899 by Miss Alice Eastwood

In this publication, Brainerd notes that his daughter, Mrs. Viola Brainerd Baird of Berkeley, California, did collect some beautiful specimens of these flowers here in the Santa Cruz Mountains, almost a century ago, on April 15, 1916.

Once our wet weather ends and our hillsides dry out these pretty little native flowers will no doubt disappear, but hopefully will re-emerge again with the rains next spring.

The leaves of your two-eyed violet resemble those of our native sweet violet.

It’s so strange… in every language I know – except my own – people make a distinction between ‘violets’,with their heart-shaped leaves, and pansies, that have very different leaves. (German: Veilchen and Stiefmutterchen, French: Violettes, and Pensées). But in Dutch, they are all called ‘viooltjes’… which I regret…

What a delightful discovery! I’m amazed at the detail on these tiny beauties, and somehow the eyespots especially captured my attention. It’s such a wonderful little designer touch.

I had not realized the striations might be guides for pollinators to the sweet heart of the flower, in effect a landing strip. Nothing is really wasted in nature; is it?

Yay! So glad I could make a good guess! It has such a happy face. Town Mouse did warn that they spread viciously, but it seems you have enough room to let it run rampant. Do they have a scent?

Great post as always. Very informative. I might have seen some hiking last spring. But it could have been another native viola.

Yes, I see this along the dirt road that is not so far from our house. Very pretty little plant. I looked it up in California Indians and Their Environment, which has a lot of plants listed and how the native people used them, but I don’t see it there either. So sweet, and such lovely colors.

What a beautiful little violet. It’s such a treat to see it.

That is one stunning little violet … what a marvellous find!

Such pretty blooms and foliage! I love the challenge of identifying a new plant 😀

What a delicate little beauty. The touch of burgundy is so pretty!

Oh its such a little beauty. I just love the way the leaves change colour too.

I absolutely love this little plant.

I grow Viola odorata and the leaf shape is so indicative of this family of plants.

Such an informative post and great photography too.

Ryan

That’s awsome, grate info and photos too.

A very sweet violet. Isn’t that the great thing about garden bloggers, you can put out a question and someone can help.

This is such a lovely post; I’ve never seen this violet around here, and I’m very partial to anything bearing the viola name, so of course I was charmed when I first read it…and forgot to leave a comment. I’ve come back to correct that.

What a unique — and darling — little bloom! You’re very lucky to have it in your garden.

Charming and useful violet info! Had to come visit when I read your comment re Filoli at Alice’s Travel Buzz. Adding you to my NorCal blogroll.