In our last bee post we noted that despite the outward appearance of our large swarm colony hive, which seemed to be thriving, that the colony in fact was coping with a significant, and potentially deadly infestation of Varroa mites. Even though the hive currently has almost 4 full hive bodies of brood, and two honey supers, left unchecked, this hive could still be wiped out completely by early winter.

Occasionally it's the strongest hives, those producing the most brood, that ultimately collapse due to Varroa infestations. Looking at our Salvia Hive from the outside it seems to be a thriving colony

To find the mites, we had to actively look for them. Passive observation of mites on bees is not a reliable way to gauge whether or not Varroa has a foothold in a colony.

Until performing mite counts, we’d only noticed an occasional mite on the bees in our Salvia hive, but the counts proved they were there in far greater numbers than we’d passively observed during hive inspections.

Our first set of mite drop counts was alarming, but nothing compared to what we observed this weekend.

Our priority in the apiary for the remainder of summer is Varroa control, and doing it early enough that our colonies can recoup losses of hive population, and still have time to build up some winter food reserves.

There are numerous methods of Varroa control available to beekeepers. Synthetic chemical insecticides, organic acids, essential oils, drone trapping, sugar dusting…the list goes on. Which method is employed depends on the level of mite infestation, time of year, seasonal temperature extremes, and beekeeper preference. There is no one silver bullet for Varroa, so we’ve had to research our options, and make some decisions about where to start.

Although we had hoped that our feral-source colonies, like Salvia, would prove to be more resistant to Varroa than commercial stock, and that we may have been able to avoid treating the hives altogether, the reality is in our apiary those hives seem to be the source of the majority of the mites…and the mites are reproducing at an astonishing rate!

Even colonies that have survived previous winters without intervention, can ultimately succumb to heavy Varroa infestations

For treatment, the use of synthetic pesticides, like organophosphates, wasn’t even a consideration for us. After studying our alternative options, and discussing treatment experiences with some more seasoned beekeepers, we’ve chosen to treat the Saliva hive with Thymol. Thymol is an essential oil, and considered safer to use during the hot summer months than organic acid (formic acid, or oxalic acid) treatments. Thymol is derived from the oil of Thyme plants, and has been shown to be effective at reducing mite populations within brood cells, but the formulation we’ve chosen is somewhat challenging to obtain here, and won’t arrive for another two-three weeks.

Thymol is an essential oil derived from the Thyme plant, that has proven to be effective at decreasing mite populations in the hive

In the life-cycle of Varroa, that’s too long, as the mite population could more than double in just a few short weeks. In the interim, to buy a little time, we’re also using an adjunct method called drone trapping, or drone brood removal, until our Thymol strips arrive.

If you watched the video in the last post, and understand the life-cycle of the Varroa mite, you now know that mite populations grow exponentially during the brood rearing period.

In a normal thriving hive, drones, male bees, are produced purely for the purpose of mating with newly emerging Queens, to serve to increase the local genetic diversity of area bee colonies. As such, drones are important, but in weakening hives, especially with high mite burdens, they can also prove to be something of a liability.

They don’t forage for food, but they do consume significant quantities of hive food stores. Other than reproducing with the Queens (which is always fatal for the drone), they serve little, if any purpose within the hive…unless you’re a Varroa mite, then you find drones to be inordinately useful.

Varroa mites prefer to reproduce, and their reproductive rates are significantly higher, inside drone cells, than worker brood cells. Drone brood cells are larger, and drones take longer to mature, than worker brood, and the net result is that more mites are produced per cell in drone versus worker cells. As an example, it’s been suggested that assuming a 5% population of drones in a hive, more mites can be produced within 50 drone cells, than inside 1,000 worker cells.[1] As alarming as this sounds, drone brood cells can be used to the beekeeper’s advantage for Varroa population control, through drone sampling and removal.

Sampling a few drone pupa for the presence of mites can help to determine whether nor not entire drone frames should be removed

Drone sampling and removal alone may not be sufficient to reduce Varroa to desired levels, but it is an IPM control method that can help to achieve some level of mite control within the colony. The logic of this method is that by reducing the amount of drone brood produced in a colony, the rate of Varroa population growth is also reduced.

Although we can’t tell a Queen where to lay drones, we can encourage her by providing conditions within the hive that are more suitable for drone rearing.

The same day we began our mite counts, we placed ‘drone frames’ inside the brood nest of each colony. Drone frames come in various forms, and can be pre-made plastic frames, wooden frames fitted with wax drone-cell foundation, which is slightly larger than worker cell foundation, or modified wooden frames like the The Oliver Drone Trap frame.

As we’re using all medium hive bodies, simply placing an empty medium frame toward the edge of the brood nest is proving to be sufficient to encourage the workers to draw drone cell comb, and encourage the Queens to concentrate drone production in that area of the brood nest.

The bees will most likely draw foundationless drone comb on this empty frame (it helps to mark the top bar of the frame so you can find it again!)

The first week the bees were busily drawing out the comb.

This weekend, four weeks after placing the drone frames, we checked for capped drone brood within each colony. Finding the drone frames was easy, as we’d marked the top bars in advance.

Timing for removal of drone frames is absolutely critical, and drone frames should never be used in hives with high mite burdens if there is any chance they cannot be removed before the completion of the next brood cycle, otherwise mite reproduction is encouraged. The goal is to remove the frames after the cells are capped, but before any drones emerge.

Some beekeepers will simply remove the drone frames and replace them with new ones, discarding the drones on those frames in every hive every few weeks, regardless as to the number of mites observed. The downside of this method is that although drones have limited purpose, consistent culling of drones reduces the genetic diversity within an apiary. After all, the purpose of drones is to mate with Queens.

Here there are likely sufficient feral colonies in the surrounding woodlands, that removal of drones in our hives would be of little consequence, but if a colony in our apiary has minimal mite levels, we’d prefer to select for, and preserve those drones that are less affected by Varroa!

To decide whether or not to remove the frames, a sample of drone pupae in the ‘pink eye’ stage are removed from the capped cells to ascertain level of mite infestation in the drone brood. Recommendations are to sample at least 50-100 drones, selecting a few at a time from various locations on the frame.

Our colony with the lowest population, the Chamomile hive, actually placed worker brood on the drone frame, there wasn’t a drone cell in sight. As such, we returned that frame to the brood nest, as this colony needs all the worker brood it can produce.

The Lavender and Rosemary hives both drew drone comb on their drone frames, and had moderate mite levels within the cells. We felt levels were high enough (greater than 30% of pupae had mites) and elected to pull their drone frames.

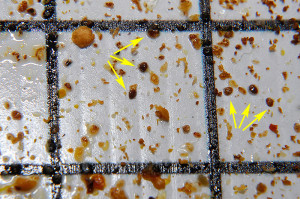

The Salvia hive however was completely overwhelmed. The mite drop count suggested a significant mite burden in the Salvia hive, but still didn’t prepare us for what we found. Drone brood sampling in Salvia revealed the horrific truth of what’s really going on inside this colony.

Too many mites to count, with more than 60% of the cells containing mites. Far worse than we could have imagined based on a simple passive mite drop count.

There is a very real likelihood of this strong hive collapsing by late fall with this severe a Varroa burden.

This colony is already showing evidence of secondary viral infections, including deformed wing virus, and it’s no wonder why.

It seemed as if almost every cell was seething with mites, in various stages of development.

Some cells had more than 6 mites entombed with each pupa. Opening any cells sent mites scurrying across the cappings in all directions. It was sickening to see the magnitude of infestation in this colony. All this has built up in just three short months since this colony was originally hived.

Despite seeing the obvious, we’re also trying to train ourselves to recognize some of the more subtle signs of Varroa problems within a colony. Spotty brood patterns are suggestive of infestation, but by the time they are easily recognized, especially by new beekeepers, the problem is usually already severe.

Notice on Salvia’s drone frame that numerous cell cappings appear to have been chewed away?

The edges of cells have a ragged appearance where a cap has been mostly removed, and those cells are now empty. This is likely due to hygenic behavior of worker bees within the hive, who are removing damaged, sick, or dead pupa from the cells.

See the holes in these cappings?

These may be the result of mites emerging from the cells, or workers starting to chew the cappings away to remove affected or dead pupa. Either way, it’s not normal in a healthy hive. The sunken cells contained dead pupa that had not yet been removed.

Here we even found mites that appear trapped in the cappings over the brood cells.

The level of mite infestation in our Salvia hive is almost enough to give us nightmares, but with appropriate management, we’re optimistic that we can still help this colony survive, and hopefully thrive.

Culling drones in the Salvia hive is not something we want to do, but by doing so, at least until this hive is treated, we hope to prevent the Varroa burden for the worker population from escalating too rapidly within the colony. Continued selective culling after treatment may help us to minimize the need of additional treatments, but it’s obvious to us that various methods of control may need to be employed in our apiary for effective Varroa mite control.

In the spring, any surviving hives will be split to propagate the colonies that are doing well, and hopefully help to select for healthier bees over time.

With the promise of high-protein tasty treats, our hens are more than happy to participate in our IPM Varroa control program

In the meantime though, while we wait for the Thymol to arrive, our spoiled hens seem to approve of our interim method of Varroa control, and are more than willing to step up to do their part…

———————

[1] D. Wilkinson and G. C. Smith. Modeling the Efficiency of Sampling and Trapping Varroa Destructor in the Drone Brood of Honey bees (Apis mellifera) . in Apicultural Research: American Bee Journal. March 2002. p. 209-212.

We just got our drone frames as well. Ours are bright green – easy to spot. For now, we’re dusting them every two weeks with powdered sugar until we get some drone brood. Once we take a sampling we’ll see what we have to do.

Do you recommend ordering Thymol to have on hand even if you don’t need it due to the long wait to receive it?

You can order Thymol gel (Apiguard) more quickly from suppliers like Dadant, or Better Bee. Our hold up is after talking to some local beekeepers they felt the Thymol impregnated strips were less harsh than the gel, and resulted in less brood kill, so we’d like to try those first, but they’re coming from Canada. If you want to have Thymol strips on hand, then yes, I think it would be best to have them handy before you need them. If there’s any more delay, we may just go the gel route, but use half the recommended dose (per Randy Oliver). We’ll see how quickly we can get the strips here though. Either way, I’m anxious to get the levels of Varroa down in that hive ASAP!

That is quite a lot of work to manage this pesty mite, but it is obvious you have no choice if you want a healthy hive. It is good that the hens can help. Always interesting and informative photos…

Beekeeping in the 21st Century is definitely a little more complex than it used to be! 😉

Great explanations, great pics as well. This must be disturbing to you. Makes me wonder how the bees in the wild actually make it now. I hope the Thymol works for you – good to know there’s something you can use to help the colony.

It is disturbing, but we’re fortunate that so many beekeepers before us in the last 20 years have also experienced managing Varroa in their apiaries, and that we can learn from their efforts. The situation with Varroa and the honey bee is slowly improving, and some bee stocks are showing promising resistance to mite infestations, but they still have a long way to go. It’s amazing how much of a stranglehold this parasite can have on some colonies.

Clare, Once again you’ve done an excellent job of explaining complicated information clearly. Thanks for your contributions to my continuing education. I hope your efforts pay off and the Salvia hive is able to survive and thrive.

Thank you Jean. I hope the images at least help to drive home to other new beekeepers the importance of taking the time to scrutinize their colonies for the presence of this parasite. We hear all too often of beekeepers who are caught by surprise when their colony has almost died out. Some early intervention can go a long way to helping colonies through winter.

a valuable post but why did i end up feeling itchy all over? mustn’t watch the movie aliens any more.

I was so itchy on Sunday watching the mites crawling all over the place. I was relieved when the chickens had finished cleaning up after us 😉

Every time I read your posts, I learn something new. Thank you!! I’m so glad you are such concientious gardeners/farmers/bee keepers. Those mites look like tiny deer ticks. Ugh!

The reproduce like fleas, but they do have a nasty resemblance to ticks. We have those too, but they mostly bite us farmers, and thankfully there aren’t as many of them 😛

Reading your posts really makes me think differently about putting a little honey on my bread. Ho amazing what’s going on with those hives – and how interesting that things can go wrong even if the beekeeper does everything correctly. Kind of like people getting sick, we keep forgetting that half the time when you get sick, it wasn’t bad nutrition or not enough exercise or too much stress – you just got sick.

Good luck!

It does make me realize just how under-priced honey is. Unless something remarkable happens, we won’t take any honey this year. The colonies are already behind because of the weather, and they need to build up as much in reserves as possible for the winter months. If we can improve the health of Salvia, and she over-winters successfully, hopefully next year the bees can share a little honey with us 😉

Clare,

This post is very eye opening and full of valuable information. Hope you get this under control very soon. Interest to see how well the thymol works.

I added a brood box yesterday! I checked only 5 of 10 frames, the bees were getting upset. Took photos of the 5 frames, no mites seen in any of the photos. I only found one drone and did not see any drone brood. Crossing my fingers this will continue.

I find photographing my inspections to be tremendously helpful. Most of the few mites we saw before doing the mite counts were observed in photographs from the inspections. Congrats on the extra brood box! The sooner they can build population, the better, just watch out for drone brood. One of our hives isn’t making any, and it has the lowest Varroa count. Once you see drone brood though, I’d go ahead and get that baseline mite count in. Good luck!

Clare, I have a bee question that you might be able to answer. I took some photos of a bee with a hole drilled in the abdomen. The abdomen was dried and brown as if sucked dry. The bee was feeding or collecting pollen, I am not sure which. It was in such bad shape, I could not believe it was alive, yet alone, still working. If you need the image to identify the problem, let me know, or I can post it on the next GWGT post. Donna

Yikes, that sounds unpleasant, for the bee I mean. I’d love to see the photo though. I wonder if the bee was host to something like a parasitic wasp larva? If you want to email a copy for me to look at, send it to curbstonevalley(at)gmail(com), otherwise I’ll watch for the photo in your next post. I’m intrigued!

You really have to have determination to get through some things. I ran off to look at the suggested post on the brush rabbit immediately after reading this post, to cheer myself up. We see brush rabbits daily, dawn and dusk, and enjoy them so it was good to read your informational post. Well good luck with your drone hygiene programs – I’m glad there’s hope.

There is hope, all is not lost, yet. We’re up to our elbows in bunnies this year. The dogs look forward to their regular morning viewing of Bunny HDTV going on outside the picture window in the living room each morning 😉 We actually can’t say the word “bunny” in the house any more without sending the dogs into a tizzy!

It seems that mites are a reality now and you’ve had to get an education not really wanted. I can imagine that it’s hard to think of your bees having a hard time developing. Distressing to say the least!

I’d go for the big guns!

It has been an education. I didn’t know very much about Varroa mites before we started down the beekeeping path. We knew even before we had bees that our hives would have to deal with this sooner or later. I’d rather be informed, and armed with knowledge, as that’s the only way we can hope to help our colonies.

Hi CV,

So sorry to hear that the Saliva colony is suffering so heavily under the Varroa mite, I do hope you are successful in treating them.

I hope so too. We’ll post when we start treatment, and follow how the hive does with the Thymol strips. Crossing my fingers!

There is so much information here to take in. I can only imagine how you must feel trying to learn all this quickly enough to be able to be a step ahead of your hives. What an incredible amount of work and must be so frustrating to see so much damage. Glad to hear you found an organic way of getting rid of the mites!

I think before I was a beekeeper I had a somewhat romantic notion of beekeeping. More an art, than a science. After all, it used to be the farm wife that kept bees in skeps in the garden. How hard could it be? As a child learning about bees the first time, I think beekeeping was much simpler then. Varroa has certainly added much more science to the art of beekeeping in the last 20 years. I’m just hoping I learn enough of what I need to know to help our colonies survive.

with such microsopic attention to detail, it becomes clear why honey is so expensive. Another first-class exposition Clare. Made me do further research and I read that Thymol can contaminate or taint the honey during honey flow and slow down the bee’s reproduction cycle. Is this chemical company propaganda? At least the hens are ‘in clover’ – honeyed eggs. Yum!

Holy Schmoley! You’re dealing with a lot of mites.

I remember picking up a beekeeping catalog in the 90s, and thinking “This is not for me. It’s too much like serious livestock management. The bees have too many diseases.”

And yet, somehow I became a small scale beekeeper.