The California Buckeye (Aesculus Californica) is endemic to California. A member of the Horse Chestnut family, it is found below 4,000 feet in elevation throughout much of the State. In the northern part of its range it typically grows as a large multitrunked shrub. Toward the south it often grows as a small rounded tree, up to 30-40 feet in height.

Adapted to growing in our Mediterranean climate, Aesculus grows well during the winter and spring rainy season, but typically begins to lose its leaves by mid-summer, and is one of the first native trees to go dormant in autumn. This species has silver-gray bark, frequently covered with lichens or mosses, and when in leaf has dark green compound leaves comprised of 4-7 leaflets.

All parts of the California Buckeye are poisonous if ingested. The leaves, flowers, and seeds of Aesculus californica contain harmful alkaloids, glycosides, and saponins.

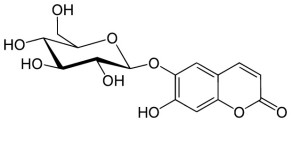

Of most importance are the toxins fraxin, and aesculin, a lactone glycoside and hydroxy derivative of coumarin.[1]

Aesculin: a derivative of coumarin, is toxic to honey bees and livestock (Image Source: Public Domain)

Despite its toxicity, historically this tree has been of value to native peoples. Some tribes consumed the seeds, but by treating them first much as they would acorns. The seeds were pounded, leached, and boiled into a gruel, before being made into a cake and eaten with meat. Some tribes roasted, and peeled the nuts, then ground them into a meal used to make soup. Others used the toxins in the seed to their advantage, including the Pomo and Kashaya, who would grind the nuts and sprinkle them into pools to stupefy fish, making them easier to catch.[2]

The California Buckeye provides important late-spring forage for our native pollinators, including native bee and butterfly species. Native pollinators that co-evolved in the presence of California Buckeyes seem to be resistant to the effects of the toxins, especially butterflies who relish the nectar from the flowers, including the Pale Swallowtail butterfly (Papilio eurymedon).[3]

European Honey bees however, a relatively recently introduced species to California, are not adapted to the toxic compounds found in Aesculus. For honey bees, Aesculus californica is like a siren in our native woodlands. Much like the sirens in Greek mythology who were famous for enticing sailors to their deaths with bewitching songs, Aesculus may lure unsuspecting bees to an early death with bewitching nectar-laden blooms.

This tiny ant is unlikely to be affected by the toxins in these blooms, but these same flowers can prove deadly for honey bees

This alluring native species produces an abundance of nectar and pollen in late spring, which, depending on climatic conditions that year, the honey bees may find irresistible. The California Buckeye is one of the most toxic native plant species that European honey bees are likely to encounter in California.[4]

The potentially fatal bee-enticing florets are borne on a terminal panicle growing 4-8 inches in length, usually in mid-May to early June. Some years their blooms are of little consequence near apiaries. However, some years, where bad weather, or drought, shortens or delays the bloom periods of other spring flowering species, the California Buckeye may regionally become the predominant forage, and the risks for honey bee poisoning are increased.

The flowers of Aesculus california have been reported by beekeepers for a number of years to yield significant honey [5], and there has been some debate as to whether the nectar itself, and subsequently the honey produced from the California Buckeye, is toxic to humans.[1,6]

There is little question however of the toxicity of the pollen. The honey bees combine the toxic orange-colored pollen with nectar or honey (called ‘bee bread’), and store it in the hive, where the nurse bees in the colonies in turn feed it to newly developing larvae in the brood nest.

Honey bees mix pollen with nectar or honey and store it in the comb until it's needed for feeding brood

Aesculus toxicity in the hive has been documented to cause the death of young larvae, which are subsequently removed from the brood nest, resulting in an irregular brood pattern. The toxin also seems to impede fertility of the Queen, who may cease laying eggs altogether, or resort to laying only drones. Some adult workers emerge with crippled wings, or malformed legs and pale bodies.

The toxic pollen is especially damaging to the brood, and a colony that cannot replace itself may be doomed to die

Foraging field bees may exhibit paralysis-like symptoms after exposure. After a few weeks an increasing number of the eggs in the hive will fail to hatch, and the majority of young larvae die before day 3, eventually leading to an absence of uncapped brood in the hive. Chronically affected colonies may become seriously weakened and die.[7,8]

Those bees that survive to emerge as young workers may be rendered hairless, pale and deformed.[9]

It takes a Queen to make a Queen - supersedure cells may be observed, but new Queens may not survive

Affected colonies often try to supersede their queens, but as the Queen’s own fertility may be affected, and it takes a fertilized egg to produce female bees (and new Queens), supersedures frequently fail.[8,9]

Bees in more urban environments usually have significant alternative foraging resources available during peak Aesculus bloom, thereby limiting their exposure.

However, hives located in more natural habitats may be at more risk for Aesculus toxicity, at least during years when alternative forage plants fail to produce enough nectar that’s more attractive.[10]

Ideally those hives would be located away from significant sources of Aesculus during the bloom period [11], but if it’s not practical to relocate a hive, then colonies can be fed honey or sugar water to help dilute the effects of the toxin.[12]

As we can’t realistically provide enough alternate forage to feed our own bees year round, we can ensure that during a spring with an excess of Aesculus in bloom nearby, that we offer supplemental feed if necessary.

Determining whether or not a colony is affected by Aesculus toxicity is not necessarily straightforward. Early photographs published in the Hive and the Honeybee of Aesculin toxicity in bees, strongly resembles bees affected with Deformed Wing Virus (we’ll discuss that in our next post), which today is a much more likely cause of the deformity.

This bee's withered wings prevent her flying. Is she suffering from Deformed Wing Virus, or Aesculin toxicity?

Symptoms of paralysis observed in field bees exposed to Aesculin, could be caused by viruses such as Chronic Bee Paralysis virus, or exposure to pesticides. Varroa mites would be first on our radar for spotty brood patterns in the hive, rather than Aesculus exposure. In other words, these non-specific symptoms make definitively diagnosing California Buckeye poisoning in hives difficult, even for experienced beekeepers, and may often be a diagnosis of exclusion once other common problems have been ruled out. As such we feel it’s important for the welfare of our colonies to be aware of the forage available to our bees, and take steps to intervene if necessary, but not get so hung up on the possibility of toxic forage, that more common pests and diseases are overlooked.

Poison pollens and nectar aren’t unique to the California Buckeye, and are found in other plant species that honey bees may encounter too, including Death Camas (Zigadenus venenosus), Cornlily (Veratrum califoricum), Mountain Laurel (Kalmia spp.), Yellow Jessamine (Gelsemium sempervirens), some species of Rhododendron (especially Rhododendron ponticum), and Locoweed (Atragalus spp).

Aesculus californica is the most common of those plants here, and although a beautiful part of California’s native flora, it is a tree that should be cultivated with care by anyone choosing to plant it intentionally. It’s not a species one should choose to shade a paddock, corral, or barn, to avoid accidental poisoning of poultry and livestock. Even though its toxicity makes it a poor choice for many gardens, its value to our native pollinator species still makes Aesculus californica an important part of our native ecosystem.

————————

[1] Penn Veterinary Medicine Computer Aided Learning Poisonous Plants: Genus: Aesculus

[2] Daniel E. Moerman’s Native American Ethnobotanical Database

[3] Callahan, Frank. Plant of the Year: California Buckeye (Aesculus californica). Kalmiopsis. 2006 Vol 12. p9-15

[4] Vansell GB. Buckeye Poisoning of the Honey Bee. California Agricultural Experiment Station Circular. 1926 #301:12 pp.

[5] Pellet, Frank C. American Honey Plants. American Bee Journal. 1920.

[6] Little, Elbert L., Jr. Atlas of United States trees. Volume 3. Minor Western Hardwoods. Misc. Publ. 1314. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 1976. 13 p.

[7] W. Stanger, L. Foote, H. H. Laidlaw et al. Fundamentals of California Beekeeping. California Agricultural Experiment Station Manual 42. 1971.

[8] Roy A. Grout. “Injury to Bees by Poisoning” in Hive and the Honeybee. Dadant & Sons. 1949. p.549

[9] Hachiro Shimanuki and David A. Knox. Diagnosis of Honey Bee Diseases USDA Agriculture Handbook Number AH-690. 2000. 61pp.

[10] “Buckeye Poisoning of the Honeybee” in Work and Expenditures of the Agricultural Experiment Stations. 1918. p.57

[11] Anthony P. Knight, Richard G. Walter. 2001 A guide to plant poisoning of animals in North America. 2001. p.233

[12] Ross Conrad. “Poison Plants”in Natural Beekeeping: Organic Approaches to Modern Apiculture. 2007. p. 177

I am really surprised at this information. I had no idea that the CA buckeye is detrimental to insects and livestock. Now I wonder about the buckeyes (‘Ft. McNair’)we grow on the farm.

I think most animals preferentially avoid them. It’s my understanding that not all trees in the genus are equivalently toxic, and that toxicity varies by species the species of tree, the species ingesting the plant, what stage of growth the plant was in (fresh spring growth being more toxic than fallen leaves), and obviously how much was consumed. I have found case reports of intoxication for Aesculus hippocastanum (goats) and Aesculus glabra (cattle). I believe the hybrid A. hippocastanum x carnea (your red horse chestnut) is a less toxic species, but if you have any concern you could try contacting a local large animal veterinarian, or animal poison control, to see if that species is of concern in your area.

Interesting post! I wonder how much of the recent decline in honey bee populations can be attributed to poisonous plants, as well as modern toxins in the environment. I thought the major cause was a virus. It is encouraging that native bees are less affected, but I suspect their situation is ultimately precarious also.

Plants toxic to bees I think are fairly few and far between. I would suspect that overall toxic plants wouldn’t have that much affect on total bee populations, as relatively few private or wild hives would be located near large plantings of poisonous plants. Man made environmental toxins though I have to presume are of far greater concern to bees, all bees, not just the honeybee. Walking down the pesticide aisle in a home center, it’s still amazing to me what is allowed to be sold to private home gardeners. Not to mention the absurd amount of pesticides applied to intensively farmed food crops.

A very interesting post. I had never seriously considered that any flowers would be toxic to bees. It would seem that introducing a non native species of any kind of wildlife is never as simple as it seems.

Fortunately most plants aren’t toxic to bees, and unless they receive large doses of Aesculus it doesn’t seem to be a problem for them. The greatest risk is in areas where it predominates, or during seasons where little else is in bloom at the same time. Blackberry usually overlaps with blooms at the same time, and I see far more bees on blackberries, than buckeyes, at least here. I agree, introduction of species to novel environments at a minimum requires species adaptation on the part of the species being introduced (to climate, feed, predation etc.), and potential displacement of species already there (the example of cane toads always comes to mind).

Clare, I wanted to tell you that the first four frames of bees arrived at our house yesterday in a cardboard box. The beekeeper set them up on the stand he had built and will be bringing two more hives shortly. Carolyn

How exciting Carolyn! Glad to hear the bees are being set up in their new home!

The California buckeye is such an unusual tree… always ahead of the seasons here. Already dying back here the leaves are turning brown now while eveything else is in it’s peak, but also the first to leaf out in early spring when oaks are still bare.

I don’t know what the bee keepers do in this area to protect their hives but there are a lot of buckeyes and a lot of hive communities in our foothills. Possibly there are enough other pollen-laden plants to choose from for the bees.

Most years the bees probably have enough alternate forage thats it’s not an issue. However one beekeeper we spoke to recently that has hives in the foothills is feeding heavily this spring, as Aesculus was blooming extensively, with little else in flower near him at the time. As a beekeeper you really just have to be aware of which blooms are contributing to a nectar flow, and hopefully not get caught by surprise. Although a lack of capped brood, coinciding with peak Aesculus bloom, should give any beekeeper a hint that something isn’t right.

We had such a wet year and delayed bloom, didn’t we? It could be that bees had little else to pick, pollen-wise.

It had never occurred to me that pollen and nectar could be poisonous. It’s a rough world out there for bees; especially if they haven’t co-evolved with the plants they feed on. gail

this is a great post… and i love the cal. buckeyes. their nuts make great decorations.

I had no clue! Clare, you really should write a book! Your wealth of info and fab photos could fill volumes. Happy Summer 🙂