It’s a little early for a Hallowe’en tale, but yesterday we made a rather grisly discovery in the apiary. After only 5 months, the Chamomile colony, despite our efforts to help, is completely dead.

If we weren’t paying attention to our hives, we might have been shocked to find an empty hive. Blamed it on ‘CCD’, or any number of other potential, intangible causes. Sometimes though, why a colony collapses isn’t inexplicable. We’ve been watching these hives all season, and carefully recording our findings as we go. Putting all the pieces of the puzzle together, it isn’t really a mystery why this colony has collapsed.

Each hive is photographed, and each inspection is logged, so when things go awry, we can look at overall trends in health, and population

Part of beekeeping, rather than bee-having, is to provide for the bees if and when they need assistance. To prevent colony starvation, we’ve been feeding all the bees in the apiary during the fall nectar dearth, which can be quite pronounced in this area. I had promised a post about how, and why we’re feeding, but I’ll postpone that until our next bee post, and for now just focus on the reasons for the demise of this hive. Rather than throw our hands up, and say ‘oh well, they’re gone’, we feel it’s important to critically evaluate any loss, and try to learn from the experience.

This colony was acquired as a purchased package colony in May, one of two colonies installed that day. If you’ve been following our beekeeping exploits this year, you may recall that this hive has always been the straggler in our apiary.

As the season progessed, Chamomile, our smallest colony, had less than half the population of our strongest colony

Chamomile’s neighbor to the left, Rosemary, set off to a roaring start, and built up very quickly, much like her feral neighbor, Salvia. Chamomile however was slower to build up population, and stores, than any of the colonies. Initially, being new beekeepers, we ascribed a large part of the difference to individual colony variation, weather, and the lateness of the acquisition of this colony. In hindsight though, there was more to it than that.

At first our concern was whether Chamomile’s Queen was well mated.

Queen breeders in California suffered setbacks this spring when foul weather hampered the production of spring Queens. Soon after she arrived though, the Queen was laying eggs, and producing what appeared to be healthy worker brood. All signs pointed to a good hive, with a well mated Queen.

Toward the end of summer though it was clear that Chamomile was struggling to store much honey. It hasn’t been a stellar honey year for many in California. Early in the season even commercial beekeepers were lamenting the failures of the both the citrus and the black sage honey crops, due in part to the protracted, unusually wet spring. Even so, Chamomile’s neighbors, although not accumulating enough reserves to share with us this season, were at least managing to provide for themselves.

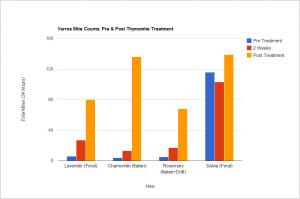

As the summer bee populations drop off as we slide into fall, lurking issues in a hive can become unmasked. By mid-August it was clear that we had an escalating Varroa problem.

Until this point, the Chamomile hive had been relatively clean, with an all-time high mite drop count of a mere 4 mites. Certainly not enough to necessarily treat the colony.

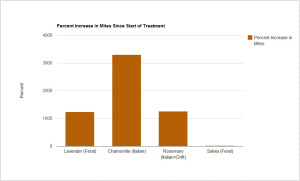

One of our feral colonies, however, had been battling a high mite count for a few weeks, so in mid-August we chose to treat all four colonies with Thymol.

By the end of the four-week treatment period however, Chamomile went from our lowest, to our highest mite-burdened colony (relative to total population).

CSI: Chamomile Hive

Looking back through the inspection logs, photographs from through the season, along with the findings today, the most notable differences in this early failed hive, compared to other colonies have been that Chamomile had:

1) Low population throughout the season. A lack of strong build up even during the months with lots of natural nectar and pollen availability.

2) A lack of drones all season. Colonies that are weak, don’t tend to produce drones. Producing drones is energetically expensive, both for the Queen, and for the colony at large. Drones consume reserves, but don’t contribute to the function of the hive, and they don’t forage. It’s like having a house full of guests that don’t contribute to the rent, and don’t grocery shop. They clean out the fridge, and don’t pick up after themselves. If you’re well off, maybe you don’t mind a few extra lazy house guests, but if you’re barely making ends meet, it’s not an expense you can afford.

During our last inspection, we left Chamomile's drone frame in place, because it only contained worker brood, and this colony needed all the population it could muster

All of our other colonies, during the peak season were producing plenty of drones, suggesting they were doing well enough they could afford that expense. Our interim Varroa control measure prior to treatment, was drone trapping, as drone cells are where mites prefer to reproduce. As such, we were closely monitoring drone production in all the hives, as it’s critical to remove the frames at the right time, or you simply breed more mites. Chamomile, however, only ever placed worker brood or nectar in her drone frames. During our last complete inspection, Chamomile was the only hive we left the drone frame in situ, because during that inspection it was still filled with capped worker brood.

3) Poor honey storage. Even at the end of the last nectar flow, Chamomile only had a few frames of honey stored. Far less than the other colonies. Likely a function of low forager population, and possibly an early indication of robbing.

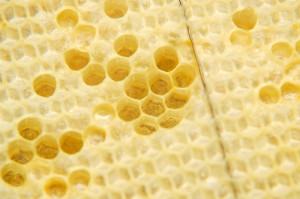

Here you can see what should be capped honey, but the honey is missing, with the caps still in place

As of today’s inspection, it was obvious that robbers had cleaned out what remained of Chamomile’s stores now the colony is dead.

Turning the frame over, it was clear robbers had taken the honey through the other side of the frame, chewing though the foundation layer, rather than removing the caps

4) Extreme Varroa mite burden. This colony experienced an early fall, overwhelming, exponential increase in Varroa drop counts, more than twice that of the neighboring colonies. This wasn’t unmasked until toward the end of treatment.

As summer bee populations naturally dwindle in the fall, weak colonies can rapidly become overwhelmed with mites, as they don’t have the population of bees to cope with the level of infestation, and any population losses due to Varroa directly, or indirectly as a consequence of vectored diseases like Deformed Wing Virus (DWV), are much more significant.

Chamomile’s Last Days

After the robbing screens were installed on all of the hives in August, Chamomile was the only hive in the apiary where we noticed yellow jackets defeating the robbing screens. Just before the recent rains, I was watching the hive entrance to assess how much pollen was going into the hives, and to watch for signs of robbing bees, and saw three yellow jackets, in succession, exiting the hive.

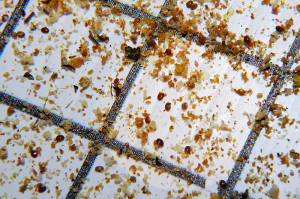

Every hive inspection starts with looking at the ground in front of the hives. Yellow jackets have been a persistent problem this fall.

I knew this was very very bad, but as the neighboring hive, Lavender, was actively defending their robbing screen from intruders, I was reluctant to open Chamomile to see what was going on, for fear of setting off a robbing frenzy in the apiary. I could only guess how much damage these Yellow Jackets were doing to the hives, as they were no doubt stealing brood from the brood nest, and attacking workers within the colony.

Yesterday, when going up to feed all the colonies, I found a disproportionate number of dead bees at the entrance of the Chamomile hive.

Despite robbing screens, and entrance reducers, these bees were dead at the entrance of Chamomile's hive. Even as I photographed this, Yellow Jackets were exiting the hive.

More evidence something was very wrong. Opening the lid, I could see the ants had suddenly made themselves at home, and only two or three bees where in the area where the food was. (I also discovered that bee suits are NOT ant proof!) Most notable was that the pollen we’d put in before the recent storms, was still relatively untouched. The other colonies have been devouring theirs. This hive suddenly seemed eerily quiet.

Removing the feeder, I could see straight down to the screened bottom board to a small pile of dead bees at the bottom of the hive. A few bees were wandering about, but it was clear the hive was completely dead.

During the inspection of the empty hive this morning, the most notable finding, other than starved, partially emerged brood, was Queen cups, and supersedure cells. It’s apparent that for whatever reason, the Queen in Chamomile either absconded, was failing, died, or was perhaps even killed by the intruding yellow jackets.

This colony was clearly trying to replace their Queen.

I accidentally flattened this supersedure cell while examining the other side of the frame, but this one was still sealed.

Our last complete inspection on September 18 showed no signs of supersedure cells, or Queen cups.

Multiple empty Queen cups were also present on a number of the frames.

Whether the original Queen absconded, or was killed, we don’t know, but in just over three weeks Chamomile went from a weak, but functioning hive, with eggs, capped and uncapped brood, and descended into panic mode desperately trying to replace their Queen, and failed.

However, even if the larvae in the supersedure cells had hatched as Queens, they likely would still have been doomed to fail. Drone production ceased here by mid-late August, in all of our hives. We haven’t seen a drone in the apiary since early September. Attempting to replace a Queen this late in the season, after the drones are gone, is most likely to result in a failed mating, and the demise of the colony. The only way to replace the Queen at this time of year, with any assurance, is for the beekeeper to replace her with a known, mated, purchased Queen.

That neither of the capped Queen cells had hatched suggests that the attempt to replace her was too little, too late. It’s likely the hive population dwindled too much, and the few remaining bees simply abandoned the hive, leaving the remaining brood, and supersedure cells, to starve.

Hive Post Mortem

The good news in all this is there are no overt signs of significant disease in the Chamomile hive. Not all diseases however leave much evidence behind, especially when there are relatively few bees remaining. Overall, putting all the pieces of the puzzle together though, it appears that the demise of Chamomile was the result of a perfect storm. A weak colony, a high Varroa burden, and relentless robbing from yellow jackets, and failed supersedures, all pushed this colony beyond the brink.

After the recent rain, the additional clues that the colony was near failure, was that a number of the bees exiting the hive were no longer the classically light blond bees we were used to seeing. There were just too many dark bees in the hive, suggesting that the neighboring colonies were taking advantage of undefended stores, and simply cleaning out the hive pantry.

Two other observations, that were somewhat more subtle, were that in the last week we had noticed that the few bees being mobbed on the neighboring hive’s robbing screen, were in fact little blond Chamomile-like bees. We questioned why when we first observed this, that bees from a weak colony would try to be gaining entrance to a strong hive. Now it’s evident this was likely a final act of desperation on the part of any Chamomile survivors, as their hive no longer was hospitable to them.

One additional observation was that this last weekend we noticed what appeared to be a number of scout bees investigating the eaves of the house and workshop. We’d seen this a lot during spring swarm season, but it seemed strange to see these bees looking for a new place to live in mid-October. Not that we want to catch a late swarm, as they’re often very difficult to overwinter, we went ahead and set out a nuc box in case there was a colony looking for a new home, not realizing they may actually have been some of the few last worker bees from Chamomile. Now Chamomile is completely dead, the ‘scouts’ have gone.

Lessons Learned?

Perhaps the biggest lessons learned from our experience with Chamomile, are when to be concerned, and when to intervene. It’s a fine dance between inspecting, and trying to provide everything we can for the bees, versus interfering, and causing disruption in the hive.

Every colony is different, but we’ve learned that even a subtle perceived weakness in a colony can quickly escalate to collapse.

From our reading over the last year, and attending numerous meetings, we knew that ‘weak Queens should be replaced’ in the fall. The question was, what constitutes a ‘weak Queen’? Is it always obvious? Obviously a hive full of drones suggests a Queen is failing, or has been replaced by a laying worker. The solution is obvious. It’s time to re-queen.

However, with a Queen that only lays worker brood, with a good laying pattern, why requeen her? In Chamomile’s case she should have been requeened in late summer when it was clear she had never built up as well as the other hives. Brood patterns aside, by sheer numbers alone, the colony was weak, and our instincts were right. We should have replaced her, rather than give her the benefit of the doubt. The signs were more subtle than a Queen that had overtly failed, but clearly Chamomile hadn’t proved her strength.

The lessons in regards to Varroa are two fold. One is, never assume because mite counts are low, that they can’t explode at a moment’s notice, especially in the fall. We proved that during treatment. We knew numbers could climb rapidly, but we didn’t know just how rapidly until September.

What this graph from our last post really showed, was that Chamomile was completely overwhelmed with mites

Even with all the homework we did in regards to Varroa, we were still not prepared for what we found in the Chamomile hive after treatment. That said, it’s now clear that perhaps some of the aberrant escalation in count was due to yellow jackets opening and robbing out cells containing larva, exposing many mites at once, rather than the gradual exposure that happens with natural brood hatching. Again, a shortcoming of natural fall mite counts.

As for treatment, overall, we consider the Thymol treatment to have been a wholesale failure, throughout the apiary this fall. Starvation, and Varroa are still the greatest threats to our remaining colonies. During our last inspection we made a conscious effort to ensure that all the colonies were still laying eggs, and had capped and uncapped brood. We did find eggs in Chamomile, but when we found eggs, we stopped digging through the remainder of the hive, to keep the inspection as brief as possible during robbing season. In hindsight, perhaps we should have looked for the Queens in all of our hives, maybe we would have been alerted to the magnitude of the problem sooner. At the very least we could have combined this hive with another before it completely failed, although, perhaps with Chamomile’s mite count, it was probably best we didn’t.

Any treatment, even ‘organic’ treatments have the potential to harm the Queen. Even if the Queen survives however, treatment can still interfere with egg-laying. Perhaps Chamomile stopped laying soon after the last inspection, and the colony simply couldn’t sustain itself as the remainder of the summer bees died off? It’s a double edged sword. Treating mites may harm a colony, but leaving mite numbers unchecked will KILL a colony.

Having a better understanding of the nectar flows in this area, next season we’ll also pay even closer attention to stores, and the need to step in and feed sooner. In hindsight, we probably should have been feeding a little earlier in the season, before it was evident that stores were rapidly starting to decrease, to maintain what the colonies had, rather than trying to catch up as stores dwindled. We weren’t expecting the nectar dearth to be as early, or as protracted as it’s been.

Lessons learned, especially in regards to timing of feeding, and managing Varroa, we hope will make us better beekeepers. We’ll trap for yellow jacket Queens early next Spring, to help prevent overwhelming numbers in the fall. We’ll be more astute to robbing (which isn’t always as frenzied as some may suggest). We’ll be more aggressive with Varroa control starting in early spring by dividing surviving colonies, forcing breaks in the brood cycle, doing regular mite monitoring, drone trapping, and treating early, and keeping the hives balanced in population to decrease the stimulus for robbing at the end of summer. If all the hives are of similar strength by the end of summer, as the remaining hives are now, the robbers simply seem to give up.

In the meantime, this morning while we were going over the Chamomile hive with a fine-toothed comb, we removed all of the frames that contained pollen, and this is why. Wax moth. One more bane of the beekeeper’s existence.

We found two wax moths inside the empty Chamomile hive this morning. It took no time at all before they moved in.

Now with no bees to defend the hive, the wax moths are circling like vultures, trying to move in and wreak their own havoc in the remains of Chamomile’s hive. They can completely destroy drawn combs in very little time. Drawn combs are valuable to beekeepers, and we’d like to keep Chamomile’s combs for our spring hive splits. The pollen will be cleaned out of the frames, and the frames frozen before being stored over winter. This will take care of any potential wax moth eggs on the comb, to prevent the combs from being destroyed over winter.

With Chamomile gone, we’re now crossing our fingers that our remaining colonies survive, although all of them are still short on reserves for winter, so I’m off to make more feed. We’ll get into more detail about feeding our colonies in our next post.

Beekeeping sure isn’t for the faint of heart. I remember your earlier post when you were contemplating replacing the queen … it must be difficult to remove a queen who is alive and producing, albeit at an insufficient level. I guess you learn to think of it as thinning a row of seedlings or pruning a tree.

It’s not! We knew a few former beekeepers who got out of beekeeping after Varroa arrived. Most admit they didn’t find it fun anymore. We did contemplate removing the Queen, but by the time we realized we should have, it was too late in the season to give a new Queen time to produce enough brood. I think next time we have a colony that’s not building up quickly enough, we’d consider that option much earlier on. It still wouldn’t be easy to make that call though.

This is fascinating information… great detective work! A great post. Thanks!

Thanks Susan. I get frustrated when I hear other beekeepers that just assume their hive disappeared from colony collapse. CCD tends to be a diagnosis of presumption, or exclusion. I think many don’t look at their hives critically enough when they die out, and if they did, often there may be a perfectly logical explanation. Varroa, robbing, starvation, and queenlessness, individually can lead to colony demise. Put them together, and there’s no question why this colony struggled. A number of apiculturists are recognizing that a lot of bee losses may be attributable to Varroa, either directly, or indirectly. Beekeepers just have to look for the evidence 😉

I was thinking of what Anne said. You have to one tough cookie to get into beekeeping with all the problems that surface and all the knowledge that you need. I would have a hard time replacing the live queen too. There is just something so special about bees, that the loss of any is sad, let alone an entire hive. I found a dead bee the other day frozen in place, clinging to a rose. It was sad to see. Your posts are so informative and I admire your investigation, documenting and reporting. I often wonder where all the bees in my garden live and if there hives are doing well.

Requeening is not for the squeamish. It is a colony-saving method, but not necessarily one of last resort. Timing is still important. I’d have a tough time replacing a queen, especially one that previously had done well. If someone told me I had to replace the Salvia queen (who survived unaided last winter), I’d probably scoff, and take my chances 😉 She’s done amazingly well this year, and even though she’s going into her second winter (some beekeepers requeen annually regardless), I’m crossing my fingers she’ll do well again this year. At the moment she’s the only really proven queen in the apiary.

I never knew beekeeping could be so dramatic! What a saga has unfolded since summer! One reassurance is that you can take this knowledge and use it to help you with the rest of the hives.

I think most us, at least before keeping bees, didn’t realize how much is involved. Sometimes I get frustrated when lucky beekeepers, who ignore their bees, get by. We do our homework, and try to be aware of what’s going on in the apiary, and still lose a colony. Beekeeping can be a challenging, but it’s also rewarding.

Hindsight being twenty-twenty and all that… Do you think you would have known (at the time) that replacing the queen would result in bees better able to survive?

I will admit that I hate the idea of culling bees, except in the most dire circumstances.

It’s certainly not a guarantee. To have had the best chance, we would have had to requeen early enough, and been very careful to balance the hive populations. After treatment was done, and seeing the hive starting to crash, I think it was already too late for this season. If we only had one hive, we might have taken the risk though. But we have other colonies, that so far seem stronger than Chamomile ever was, that we’d rather split next spring if they survive the winter. Those are hives we want to support. Not try to hold up a weak colony at any cost. It is a tough call though, I still feel bad for the demise of the rest of the colony, short-lived though they are.

I wasn’t particularly attached to this queen, and am actually somewhat relieved that her genes now won’t find their way into the local feral gene pool. It’s a bit like choosing not to breed from a sub-standard hen, that’s a poor egg-layer. This queen was a poor egg-layer, in volume anyway.

In this case, as this colony was never strong, it’s not necessarily bad that it failed. With as much trouble as bees are in, it’s better to select for those colonies that don’t need as much hand-holding. On the other hand, if we’d considered requeening early enough, I wouldn’t necessarily have minded bringing some hardy Russian, or VSH stock into the apiary either 😉

I think in the future we’d just rather avoid package colonies, on focus on splitting surviving overwintered colonies. Our ferals so far have performed the best for us. Now we just have to wait for spring…

Well, the other comments say exactly what I would have said. I never realized just how difficult they are to keep. I always thought that hives were relatively trouble free. There really are a lot of variables in keeping bees. Here’s hoping that next year you will have a better idea as to how to protect your hives more effectively.

Clare,

Sorry to hear about the loose of the hive, it is very sad. I think to start with you had a poor queen. I’ doing an inspection in the morning, worried about beetle larva, having killed around 200 mature beetles. Our bee club did a honey tasting last night.

So far (crossing my fingers) small hive beetle isn’t a very big concern in this area. On the other hand Varroa is a virtually year around problem as our weather is so mild. Some beekeepers are reporting having seen a few beetles near here, but not in the numbers some of you are dealing with (or Hawai’i at that is inundated at the moment). I hope your beetle problem isn’t too bad. Good luck on your inspection tomorrow.

Aren’t honey tastings fun? So far Black Sage, and Leatherwood are my favorite! 😀

Fascinating analysis. Change one or two variables (stronger queen, better honey flow, less robbing, etc.) and the outcome could have been different. Is real root cause analysis even possible in nature? I am thinking there are too many variables and unknowns. Thanks for sharing this!

You’re absolutely right, there are a lot of variables. So many things that contribute to the strength or weakness of a hive. Many more even than listed in this post. Some of the big issues, although obvious, may not be the sum total of the problem, but they are often the ones we can see, and potentially do the most about. The only thing I’ve truly learned about beekeeping this year, is the bees know more than I do, and I have soooooo much more to learn from them. 😉

Wow, you’ve had your share of troubles this fall! Between the dead trees under the driveway and the loss of the Chamomile hive, I think you deserve a break. Very interesting, though, how you are working on figuring out what really went wrong…

I’m just glad the weather is staying beautiful, making it the perfect time for fall planting. Compared to dead trees, and dead hives, I consider planting to be a welcome break! 🙂

Clare I am so sorry to hear about the loss of the hive. This has been a trying adventure to say the least but I have such admiration for your patience, understanding and persistence in continuing your adventure. I am amazed at all you have learned and taught us over these posts.

I’m amazed how much we’ve learned about bees this season. Perhaps the most important lesson is that even in nature, not all hives survive. Those that are weak, do not divide and reproduce. That said, it’s not an excuse to be a lazy beekeeper, but to learn from events such as this in the apiary, so we can do our best for the colonies that remain. I’m excited to see how much more we learn next season!

Hi Clare,

Sorry to hear Chamomille has failed, but as you say there are lessons to be learned and it’s all experience that you’ve gained and can now move forward.

That is really is large part of beekeeping. Experience. Which thus far we have relatively little. The bees always have something knew to teach us, providing we’re willing to learn.

Beekeeping is quite an adventure and quite a sharp learning curve aswell. Clare you’ve gained so much knowlege and experience in the past year and I’m sure that all will be put to good use as you prepare for next year.

It has been a steep learning curve the first year. Probably a good thought for a end of season summary post. “Lessons learned as first year beekeepers”. The challenge is learning what one needs to know in time for it to be useful. There a defined points in a beekeeping year. In spring, learning how to prevent or capture swarms was important. During bad weather, knowing how to supplement feed in the hives is important. Critical in fall management is knowing how Varroa is affecting the hives. What to do if a hive goes queenless. How to prevent robbing. How to organize the hives for winter. The trouble is that many of the management decisions that pop up need to be made more or less immediately, like Queenless colonies, or dealing with a robbing frenzy. Each time we open a hive, we don’t know what we’ll find, and if we find something out of the ordinary it helps to know what do then and there, rather than closing up the hive and going to look it up, only to come back and open the hive again. Eventually, with experience, we hope much of it will become second nature.

I’m far behind in my blog reading and just found this post now. I am so sorry to hear about this loss. It’s heartbreaking just reading it, I can’t imagine how you must feel. So much work only to lose them. But you have pointed out quite rightly that this is all new to you and you have learned so much this year (and your readers with you!). Hopefully your experience will help with your decisions next year and your hives will thrive.

Our think our experience this year is already helping us to plan for next year. At the end of winter as the warmer days return we’re hoping to be very busy in the apiary! 😉

What a fascinating story. Great detective work. You must have a science background. I hope you have better luck next year and get some honey for yourself. Lou

I do have a biology, and medical background. I have one of those ‘need-to-know’ brains. I also tend to be more proactive, than reactive too, so if I can learn from one experience, to prevent it from happening again, I try to seize that opportunity. Hopefully next year the bees will have a little extra honey to share, although I’m fine not taking it if they need to keep it. These days I think most beekeepers expect not to take honey the first year, unless they have a very strong hive. Our strongest though, a feral colony, made a lot more bees…than honey! 😛