In a previous post we reported that we’d uncovered a tremendous Varroa mite infestation in the largest of our bee hives, the Salvia hive. It was clear this colony was in jeopardy.

This drone (male) is one of many in the Salvia hive that hatched with a mite attached to its thorax (click any image to enlarge)

Treating Mites

There was some evidence of hygienic behavior in these bees, as they were removing at least some of the mite infested brood. However, due to the overwhelming level of mites in the Salvia colony, we elected to treat for Varroa using Thymol, an organic oil.

This pupa, in the strawberry-eye stage, has just been uncapped by the worker bees, and will be removed from the brood nest. Such pupa are often affected with mites, or viruses.

When choosing to treat for Varroa, it’s important to treat early enough in the season that the colony still has time to build up its population of winter bees. Winter bees are unique in that they have longer lifespans than summer bee populations, and a colony’s winter survival depends upon the presence of a strong population of these long-lived bees to get them through to spring. In this area, mid-August is the time to apply any mite treatments, so the bees will have at least two full brood cycles to produce their winter bees before the foul weather sets in.

Any treatment has the potential to cause harm within the hive, even treatments with organic oils and acids. How and when treatments are applied can affect the degree of potential brood kill, or Queen loss, but whether or not either happens isn’t always predictable. It’s important to know that many of the products available for treatment of Varroa work by releasing vapors that are noxious to mites within the hive, and the amount of vapor released is affected both by the dose applied, and ambient hive temperatures. As such, when treating colonies it’s important to be mindful of weather conditions during treatment.

Thymol is an organic oil that is used for treating colonies infested with Varroa mites (Varroa destructor)

There are various formulations of Thymol on the market, including gels (ApiGuard®), crystals, wafers (Api Life VAR®), and strips (Thymovar®, Thymomite®). We elected to use Thymol strips, which weren’t readily obtainable here, so while we waited for their arrival, we resorted to interim measures of mite control.

Finally, the Thymol arrived. Before applying the strips, we inspected each colony, and removed the drone frames in the Salvia and Rosemary hives. The Lavender and Chamomile colonies appear to have already ceased drone production for the season, and both of their drone frames were filled with worker brood cells.

It’s important when treating colonies, even with organic oils or acids, to harvest any honey that needs to be harvested BEFORE treating. Although the treatment isn’t toxic per se, it does leave a residue in honey and wax for some weeks after treatment, and may taint honey flavor.

Capped honey frame - If we were going to harvest honey, we would need to do so prior to treating the colony, as the honey's flavor will be altered by the Thymol

The honey stores in each colony were recorded, and as this is the first season for these colonies in the apiary, and our weather has been generally cold with below normal temperatures for this season, all of the hives seemed relatively low on honey, so we elected not to harvest any this year.

Even our largest colony only had 10 medium frames full of honey and nectar. Our smallest had only 1.

We noted the number of brood frames in each colony before deciding how much Thymol should be placed within each hive, per the manufacturer’s recommendations, to prevent over-treating the colony. As it was put to us some time ago, all Varroa treatments involve trying to “kill a bug, on a bug”. The goal is to eliminate the parasite, not the patient.

For the smaller colonies, Chamomile, and Lavender, we treated with one half of one Thymol strip. The half strip was cut in two, and the two pieces placed at the top of the brood nest in the corners furthest from the entrance. Neither of these colonies had particularly high mite counts.

For the two large colonies, Salvia, and Rosemary, a whole strip was divided in half and placed similarly.

The Thymol strip was placed on the frames at the top of the brood nest. Bees in the area of the strip retreated immediately

It was apparent as soon as the strips touched the frames that the bees were offended by the strong Thymol odor.

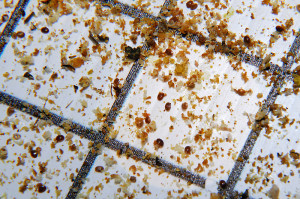

The hives were reassembled, the screened bottom boards were closed (using the sticky boards), and entrance reducers were placed. Too much airflow during treatment reduces the effectiveness of this Thymol treatment.

The bees were initially confused by the entrance reducers, but soon adapted to having a smaller front door.

It didn’t take long to see some increased activity at the hive entrances, especially in the colonies that received the higher dose of Thymol. Overall though the reaction to the Thymol odor wasn’t as much as I’d expected. It may have helped that we installed the strips late in the afternoon, as the fog was rolling in and air temperatures were starting to cool. After 24 hours hive activity seemed to have returned mostly to normal.

As we left the apiary, we could see the two hives on the left (which had the higher dose of Thymol applied) had much more activity around the entrance

After two weeks, we removed the bottom boards, cleaned them off, and reinstalled the boards for a 48 hour mite count mid-treatment. The mite count in Salvia has decreased slightly, from 116 mites per 24 hours pre-treatment, to 103. Not a particularly significant reduction yet.

So the question is, how will we know if our Thymol treatments have been effective? One thing that is important to note is that it’s apparently typical when treating with Thymol for there to be a delay in the drop in mite count. This makes sense when you realize how Thymol works. Thymol is effective against exposed Varroa mites. Those on adult bees, newly hatched bees, or lurking on comb before cells are capped, but it doesn’t reach the mites trapped inside the capped brood cells. For it to be effective, it must remain in the hive for a minimum of four weeks, so the vapor is present through at least one complete brood cycle. So after two weeks, we’re only now half way through treatment.

Any mites entombed in the cells with the developing pupa (yellow arrows) won't be affected by the Thymol vapor until after the bee hatches

Per the manufacturer’s directions, a second dose is to be applied after two weeks, without removing the first strips. We’ll continue with treatment and apply the second dose of Thymol this week, and repeat the counts again in another 14 days to see if the mite population shows evidence of decreasing, and then re-evaluate our hives at that time, and decide whether to continue for one more round of treatment.

Thwarting Robbers

As if fighting Varroa mites isn’t enough for the bees to cope with, we’re sliding into late summer, and the native flower blossoms have faded. Late summer in this area typically means a nectar dearth, and with that comes ‘robbing season’. Bees either from neighboring or nearby managed or feral colonies will exploit the stores of weaker hives, often cleaning out weak hives entirely of stored nectar and honey if given the chance.

Honey is honey, and when food supplies are short, bees will take it anywhere they can find it, even from their neighbors!

During the inspection just before we applied the Thymol strips, we noted some early signs of robbing. Hive boxes that were removed during the inspection, if not immediately covered, were subject to bombardment by bees from our other hives. Bees were wrestling on the landing boards and on the ground, as the guards defended their stores.

Bees aren’t the only robbers though. Last Saturday afternoon I noticed a few yellow jackets lurking around the hive stand for the first time this season.

In some areas yellow jacket attacks on hives can be the greatest threat to an established colony. We’ve had a history of having some rather formidable wasp nests here in the past couple of years, so we knew we needed to be alert to their presence in the apiary. They’ll steal pollen, raid honey stores, kill brood, and viciously attack adult bees. They typically will start with the weakest colony and then proceed through the apiary.

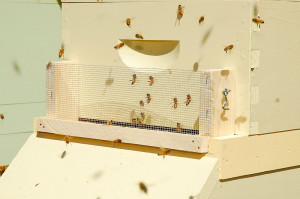

Although robbing screens are available commercially, we really need to install them as soon as possible. Fortunately, at a Bee Guild meeting last fall, Dr. Eric Mussen, Extension Apiculturist from the University of California at Davis, had provided attendees with a handout describing a design for a homemade robbing screen.

A robbing screen positioned over the hive entrance is intended to prevent non-resident bees from reaching the hive entrance. It may also be effective against yellow jackets

This screen could potentially thwart both neighboring honey bees, and yellow jackets from raiding hives. This screen, placed across the entrance, would permit resident bees to come and go, but neighboring bees get confused when they land at the entrance, and can’t find their way in.

We spent Saturday night constructing four of these screens, one for each hive, to install first thing Sunday morning.

In the morning we found 3 yellow jackets outside the entrance to the Salvia hive, fighting over a dead bee pupa. What wasn’t clear was whether they had removed the pupa from the hive themselves, or if this was one that had been dragged out of the entrance by an undertaker bee. Regardless, the wasps were fighting furiously over it.

Soon thereafter, an adult bee with deformed wings rolled out of the entrance of the Salvia hive, and onto the ground.

No sooner had she hit the ground, than she was immediately attacked by a yellow jacket, and killed. After not seeing these wasps for most of summer, it’s clear that it’s now very much yellow jacket season here. The screens have now been installed on all the hives, and will hopefully help to protect the colonies, their stores, their brood, and take the pressure off of the guard bees at the entrance.

Each screen cost less than $4 in materials to make. We used some scrap wood, and metal vent screening (the metal seemed more sturdy than plastic window screen). Each screen is anchored to the hive with a hook-and-eye latch. Although it led to some air-traffic confusion initially, the bees have adjusted to the screens very well.

Resident bees climb the screen and fly out to the field, and learn to fly down to the entrance. Robbers land on the landing board and walk forward, getting stuck on the outside of the screen

Now we’ll just have to see how effective they really are at excluding the yellow jackets. We’ve found some very large nests on the property in the past, and if necessary, we’ll place traps to help decrease their population near the apiary. It would be awful to succeed in reducing Varroa mites in the apiary, and then lose a hive to marauding wasps!

If there’s one thing that stands out to us as relatively new beekeepers, it’s the constant barrage of challenges that honey bees must face every day. Between mite infestations, hive incursions from ants, wasps, wax moths, and small hive beetles. Not to mention raids on hives from curious wildlife, and the hazards of pesticide-laden flowers. It’s made us appreciate just how undervalued honey really is.

Any thoughts on why the strongest hive – the one originating from a population so healthy that it spawned multiple swarms last spring – is the most heavily infected? Did they bring the mites with them? (I remember a few were spotted during your early inspections, and I doubt the attic had been treated.) Or were some of the mites carried over by the disoriented workers wandering over from the purchased bees next door? Did the cool summer weather play a role? or Salvia’s reproductive success?

So many questions. A recent article on beekeeping in the Mid-peninsula seemed to imply that all you had to do was get a hive, some equipment and some bees and then you could sit back and let Mother Nature do all the work. Mother Nature has some surprises up her sleeves.

May the strips be effective and Salvia prosper.

The purchased ‘package bees’ are actually quite clean, and have been since they arrived (likely treated before they were shipped).

I think the biggest reasons for Salvia’s explosive mite problem are two fold. One, because these bees were survivor stock, and had done just fine without intervention over winter, we didn’t do anything special to purge the colony of mites they came with when they were hived. We presumed, erroneously, that they must be able to cope with whatever mite burden they may have had. In retrospect, even a dusting of powdered sugar may have been enough to drop the phorectic mite count enough, that they wouldn’t have built up so much by July.

The other ‘mistake’ we made was not dividing this hive into two or more colonies earlier in the season. They had a very early start (swarming the end of March) compared to our other colonies, and they arrived with a fertile Queen that started laying eggs immediately (we had capped brood 10 days after hiving this swarm). The first round of brood would have been helping to increase Varroa populations straight out of the gate.

These bees have produced more brood (and a lot more drones) this season compared to our afterswarm (that was caught later, and arrived with a virgin Queen), and our package bees. As such Varroa has had more opportunity to increase it’s population too.

Everyone we spoke to kept suggesting not to split the hive the first year, but in hindsight, with as strong as this colony was, and the fact these bees produce much more brood than honey, splitting the hive would have been the right thing to do. It would have produced a young Queen (who would be more likely to survive winter), and it would have forced a break in the Varroa breeding cycle, at least for the new half of the colony.

Next spring, if this colony survives winter, we’ll split, in fact, we’ll split any surviving colonies as part of our Varroa management. It breaks the Varroa breeding cycle, and doubles your hives, increasing the likelihood of some of the colonies at least surviving the winter months.

Wow, I had no idea! Your description of bee keeping makes me truly appreciate the honey I so enjoy. You are a Bee Advocate, hugs Gloria

Being a beekeeper has really made me appreciate honey too! Those girls work HARD! 🙂

I don’t like yellow jackets at all. I had no idea that there were robbers lurking to trounce on the hives…I do love reading these posts…thx for the wonderful update and I hope the mite problem is reduced…

We had heard from other beekeepers that yellow jackets could be a problem, but I had no idea how vicious they are until we saw them fighting the bees!

Hi Clare,

I do like to see updates on your Bees; no doubt because I love having them in my garden, so having a sneak peek into their lives is very interesting.

I do hope the Thymol is successful in getting rid of some of the mites for you – and of course that the screens deter intruders.

So far the screens seem to be helping with the yellow jackets, but we’ll see that continues to hold true as we get closer to autumn.

This is quite interesting. I didn’t realize that yellow jackets were such fierce predators. I hope that your treatments work.

We didn’t realize there were so fierce either. That’s the think about beekeeping, we learn something new every day!

Clare,

Sounds like you are getting the mites under control. Yellow Jackets are bad here too, all over our compost 100 ft from the hive. Been seeing yellow jackets at the hive and finding dead ones too. Several weeks ago there were more jackets at the hive than what we’ve seen lately.

Randy, are you doing anything to try to keep the yellow jackets from entering your hives?

We lost 6 hives to Colony Collapse Disorder, got new bees and then lost one of those to yellow jackets…yes beekeeping is a very involved occupation! Good luck with your mites (we have never had to move beyond powdered sugar). We are trying to decided whether to harvest this year or not due to the cool summer.

This was an excellent post and I’m bookmarking it so hubby can read it too…thanks for all the detailed info! kim

That’s my fear. We do all we can to keep our hives healthy, and still lose them. I’m hoping that by knocking mites down, we’ll keep some of the secondary diseases under control too. We’ve already seen deformed wing virus in the Salvia hive. At this point we can only do our best, and see how things turn out next spring. The yellow jackets though I feel like we have a little more control over, and hopefully this ounce of prevention will pay off.

Incredible information; interesting about the yellow jackets too. I hope you are able to get rid of the mites and have a healthy hive again!

I hope so too, we’ll update on the hive’s progress once we finish this first complete round of treatment!

Clare, I always learn so much here. After reading your bee posts, I always wish I could raise bees. Same with the chickens. Turkeys, not so much. Today one thing you noted was that yellow jackets attack bees. For the first time yesterday, I saw a bee and a yellow jacket going at it. Neither died, but they were really fighting like in the cartoons, rolling over in a ball like flying pattern. I never saw a winged fight before and I just stood there amazed, but both flew off. And I have to say that bee was really agitated by the way it circled the garden so fast. Glad I was inside looking out.

It is impressive to watch them fighting. I was just shocked at how quickly the yellow jackets pounce on weak bees on the ground near the hives. If I blinked, I’d probably miss it! My biggest concern when I saw them wrestling over a dead bee pupa though was that they’ve already been successful entering the hives. Hopefully these screens will keep them out. If they don’t I’m not sure what we’ll do next, other than trapping that is.

Clare, you’re absolutely right about honey being under appreciated. Once again you’ve provided me with information I had no idea about. Bees getting robbed by other insects! and attacks by wasps. I simply had no idea about these issues. Thanks again for these informative posts.

In my opinion, it is liquid gold, and should be priced accordingly 😉

This is certainly a soap opera of the highest order. It requires so much effort and attention, and you are a great caretaker of these valuable insects. I wonder what the honey would taste like with that infusion of oregano. I hope things start to turn the corner for the best.

I read that Thyme leaves a somewhat menthol like flavor in the honey. It does dissipate, and certainly by next year’s honey harvest it would be gone. I certainly wouldn’t harvest after treating this year though. Menthol flavored honey doesn’t sound very good to me 😛

Dear Clare, Another fascinating posting. Yes, honey is grossly under appreciated and valued. P. x

I’ve certainly learned to better appreciate good honey, and I think it’s worth every penny to buy it from a local source too. 🙂

Wow, I am speechless! I don’t know if ‘Beekeeper’ is a title that does your work justice, or it is a gravely under-appreciated title for the amount of knowledge required to keep a healthy bee hive? Clare, your post was fascinating. Thanks for sharing your expertise and experiences.

I think until we’ve been beekeepers we all have that notion that bees rather keep themselves! I erroneously presumed that they’d need little from us. Was I wrong! 😛

Very informative and enjoyable post. I read the whole thing! lol.

LOL, sorry, it was a little long…I was behind on my bee posts 😉

I’m never going to wince at the price of a jar of honey again. I hope your mite treatment is effective and that your hives don’t get robbed. Good luck.

We didn’t harvest any honey this year, although hopefully we will next year. I think anyone who is able to keep their bees healthy enough that they’re producing an excess of honey, deserves a fair price for their honey. The days of hives producing 400lbs of honey each, for most beekeepers, are long since past.

Clare, What a huge commitment beekeeping is~It’s not for the detail challenged. AND, you have other critters, crops and gardens to care for~gail

As we’ve seen for ourselves at various meetings with beekeepers, there seem to be two sorts of beekeepers. Active, proactive beekeepers that ensure their hives are configured correctly for the season, where health and disease are monitored closely, and appropriate actions taken when necessary to ensure a healthy colony. And then there are what we term the ‘bee havers’. Those that have bees, and presume the bees can do everything for themselves, (including cure their own ills) and all they as bee havers need to do is harvest honey. Most of the ‘bee havers’ I’ve met, don’t keep their bees for very long. There is a lot to know, and learn, and just when you think you’ve caught up, the bees will always throw you a curve, and teach you something new 😉

I wonder how the robbing screens will work for mortician bees, carrying out dead bees?

(Did you see that there’s reason to be optimistic for my friend’s hive that was sprayed with insecticide? Fingers crossed…)

Actually, the undertakers haven’t had any trouble at all. Once they’ve acquired the hang of flying straight up before they fly out, they seem fine. That said, we have had some deformed wing virus in Salvia. Those bees typically would crawl out of the entrance, and fall to the ground. I suppose they can still crawl up the screen, but I suspect they may not leave the hive as readily with the screens in place. That’s probably still better than fending off yellow jackets though. (I did see your update, I’m keeping my fingers and toes crossed that they can recoup their numbers, and head into winter with a strong colony).

What a gripping post Clare – it makes me appreciate why honey is so expensive. It’s a constant battle and learning experience isn’t it to keep the hives going from year to year………….and now there are wasps to contend with aswell!