Last week’s glimpse into some historical breeds of American poultry made us realize that in fact the oldest chicken breed here at Curbstone Valley, is our feather-footed Dark Brahma, ‘Frodo’.

We decided to do some digging into the history of this breed…and inadvertently opened up a rather large, and controversial, can of worms. It seems that Frodo’s ancestry is murky at best.

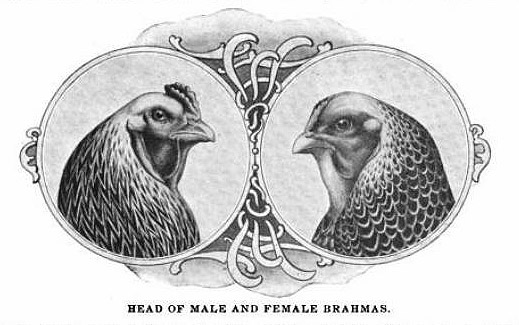

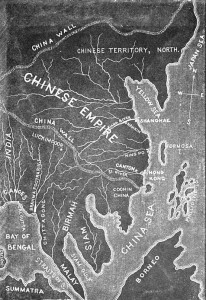

Today the Brahma fowl fall into the Asiatic class of poultry. The ancestors of the Brahmas were known as Chittagongs, Gray Shanghaes (now Cochin), or Brahma Pootras.

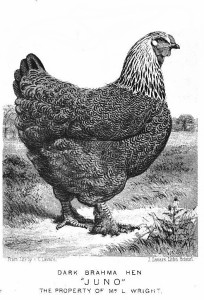

The controversy surrounding the origin of Frodo’s breed originates with two prominent poultry-men in the mid-late 19th Century. Lewis Wright of London, England, and George Pickering Burnham of Melrose, Massachusetts. These two men argued extensively in the published literature, for many years, about the true origin of the Brahma breed. Wright contended the breed originated from stock brought to Connecticut, via New York, from East India. Burham says the original stock was imported from Shanghai, China, and that he was responsible for developing what became the Brahma breed in America.

Lewis Wright contended in his book The Brahma Fowl: A Monograph that the Brahma originated with Gray Shanghaes (now Cochins) imported into New York from Luckipoor, up the Brahmapootra River in India. The birds were reportedly obtained by a Mr. Nelson H. Chamberlain of Connecticut in 1849, shown in exhibition in 1850 in the United States, and subsequently exported to Britain. In this book Wright states “The Brahma Fowl was unquestionably first introduced into England as late as the year 1852, when two pens were shown at Birmingham by Mrs. Hozier Williams and Dr. Gwynne. It was said this fowl was a new breed, imported from India.”

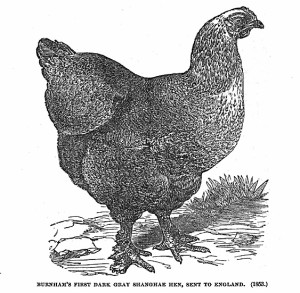

Burham disagreed with Wright’s origins of the Brahma. Burnham declared to Wright that the written historical record of fact states that “Mr. Geo P. Burnham exhibited in Boston the first Gray Shanghae fowls ever seen there; from which stock, bred in his yards, Dr. John C. Bennett produced the first so-called ‘Light Brahmas’ ever shown in the world.; (also that) Mr. Geo P. Burnham sent to England, early in 1853, the first trio of ‘Dark Brahmas’ ever seen there, or anywhere else, which latter (from the same original stock) went from Mr. Burnham’s yards in Melrose, Mass., direct to Mr. John Baily, of London.”

Both men agreed that the breed originated in the United States, before being exported to Britain. The principle bone of contention seemed to be the origin of the stock birds (China or India) and who specifically was responsible for developing the breed in America.

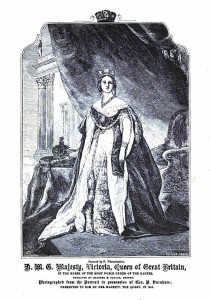

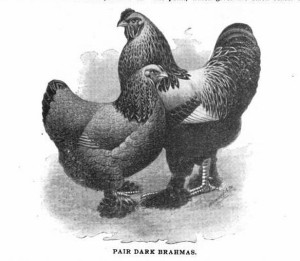

George Burnham, in his book The China Fowl overtly states “I originated the Dark Brahma fowl in my own yard, at Melrose, Mass.” In a direct rebuttal to Wright’s assertions in his book of 1871, Burnham states “The Dark Brahma, or Dark “Gray Shanghae,” is my patent, Mr. Wright. I originated it, in 1853…Look over the records, and see if you can find any “Dark Brahmas” spoken of — anywhere on earth — until my first splendid trio went out to John Baily of Mount Street, London”. He further states “…I have never seen a finer lot of the LIGHT variety than those I shipped to her British Majesty in 1852, from my yards; nor have I ever seen a better trio of the DARK strain than the three splendid birds I first shipped in 1853 to John Baily, of Mount Street, London.” Believe it or not, Baily paid $100 for this trio of birds in 1853. That’s more than $2,800 in today’s money!

However, Lewis Wright countered Burnham with “So far as positive evidence is concerned, it must be considered decisively the fact that Burnham’s account is a deception…and that all the genuine ‘Brahmas’ were bred from the original pair first brought into Connecticut by Mr. Chamberlain [from India].”

History does indeed acknowledge that George P. Burnham sent 9 of his best ‘Brahma’ fowl to Queen Victoria in 1852. However, in Burnham’s book, The China Fowl, he almost contradicts himself by saying “I never sent over to Her Majesty any so-called ‘Brahmas,’ early or late. I never said I did. I never pretended I did; and no one, save Lewis Wright, has ever said, or pretended, I did!”

Indeed, in Wright’s Brahma Fowl of 1871 he declares “Mr. Burnham, of the United States, who, it will be remembered, sent over some of the earliest so-called ‘Brahmas’ as a present to Her Majesty, in 1852 affirms that he originated them.”

Burnham does go on to say that between 1852 and 1853 he did breed over sixteen hundred “Gray Shanghaes” in his poultry yards in Melrose, Mass., and proceeded to send them all over Britain and the United States, but he contends that he never once called them “Brahmas” (considering that name to have been an invention of Wright’s). Burham’s hang-up seems to be on whether these fowl are called ‘Brahma’ or ‘Shanghae’. Brahma as a breed name didn’t become popular until the 1870s, and up until 1871 Burnham called all of his birds Shanghaes. Was the crux of the entire argument simply a squabble about what the breed was called? Surely the argument runs deeper than that, but thus far, at least part of this squabble really seems to have been that petty. Regardless as to what Wright or Burnham called them, reportedly breeding pairs of Burnham’s birds, after having being received by the Queen, were briefly valued in excess of $150! I suppose that amounts to today’s equivalent of ‘The Colbert Bump’. Sorry Frodo, as much as we’ve become smitten by the Brahma breed, even Stephen Colbert couldn’t get us to spend that much for chickens!

So, wading through (some of) the arguments about Brahma origins, if Burham’s account is true, then all ‘Brahma’ fowl have origins in Chinese Shanghae (Cochin) stock, imported from Shangai, via New York, to Burnham’s Melrose poultry yards between 1849-1850. The breed was bred and refined by him (and others from his stock) in New England, and exported to Great Britain, and his birds alone were the antecedents of the Brahma breed.

In 1921 though, the American Poultry Journal published a piece on the Light Brahma supporting Wright’s assertion that Chamberlain in fact originated the breed. According to C. C. Plaisted of Connecticut, the oldest breeder of Light Brahmas at the time “The first pair of these fowls, about which there has been so much discussion and so much written, was brought by one Charles Knox to Mr. Nelson H. Chamberlin, a resident of Hartford, Connecticut, in 1847. They were first bred by Mr. Chamberlain in 1848. Mr. Chamberlain paid for his first pair of these fowls the sum of five dollars–considered at that time a fabulous price…Mr Knox reported seeing two pairs…just arrived on an East Inda vessel, and that he had the refusal of the pair until the next trip…The result was the selection of the grays as a venture and their removal to Hartford.” The remainder of the 1921 article alludes to Burnham as nothing more than a mercenary author and marketer. Perhaps that is true…after all, how else does one garner $150 for a pair of chickens in 19th Century America!? The problem with history, is it’s dependent on the transcription and interpretation of those who write it.

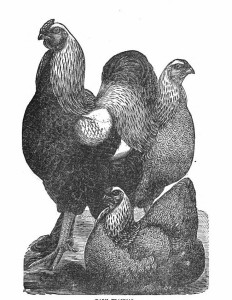

Regardless as to the quibbles over who developed the breed, or where, it’s clear that this breed was phenomenally popular in the mid-late 1800s, and along with the Cochin fowl, triggered a period of ‘Hen Fever’ in the United States and Britain around 1850. The Brahma’s popularity persisted for more than 30 years unabated.

In 1871, an article in Southern Farm and Home Magazine stated “When turkeys are difficult to rear, the Dark Brahma ought to be introduced on account of its size; for Christmas dinners it is a fair substitute for the former. We have one that at five months weighed eight pounds.”

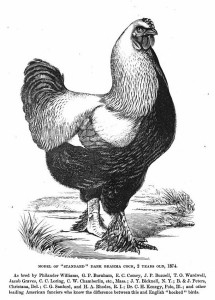

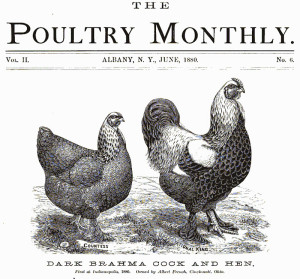

In an 1880 edition of Poultry Monthly, is a lovely article about a prize-winning Dark Brahma, a cockerel named ‘National King’, and one of his hens ‘Countess’. ‘King’ had just won first place in the National Show in Indianapolis in 1880.

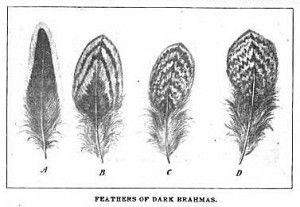

However, in 1886, despite the Brahma’s popularity in the mid-19th century, it is stated in the First Annual Report of the State Board of Agriculture. (Rhode Island) that “The Dark Brahmas: Have fallen into disfavor. Why, is a mystery. I can attribute it to no reason beyond the fact that as exhibition stock they are exceedingly hard to breed up to 92 or more points of excellence owing to the requisite pencilling demanded in a first-class specimen.” Indeed, other articles state that due to difficulty in breeding (for accurate color), that the Dark Brahma in the United States is less popular than the Light Brahma.

By 1901 however, their favor appeared to be returning. A beautifully illustrated article in The Feather in 1901 summed up the breed as:

In 1903 an article in Commercial Poultry highlights the commercial value of the Dark Brahma breed:

1. They will stand more cold than any other breed.

2. Their combs are small and will not freeze in the coldest weather.

3. They are a very heavy winter layer, laying beautiful, large brownish eggs.

4. Chicks will mature and make broilers from two to four weeks ahead of other breeds.

5. Can stand confinement far better than other breeds, and will not fly over a thirty-inch fence.

6. They cost no more to keep than a scrub, and when matured weigh from nine and a half to fourteen pounds, making one of the finest table birds that can be raised.

More than a century later, despite the nebulous history of the Brahma breed, it is accepted by those that own and breed them now that they are productive birds of an extraordinarily pleasant disposition, and we are very happy to have Frodo as part of our flock, regardless as to his origins.

By next Friday we hope to bring you news of Frodo’s reintroduction to the flock…providing our persistently pecking pullets will permit him to join them, without doing him any further harm.

_____

Further Reading, regarding both versions of this ‘fowl’ controversy:

Wright, Lewis The Brahma Fowl: A Monograph 2nd Ed. 1871 Orange Judd and Co Publishers.

Burnham, George The China Fowl: Shanghae, Cochin, and “Brahma” 1874 Rand, Avery, & Co., Boston.

I’ve been contemplating getting brahmas. Tom doesn’t like the feathered feet, but of course, he’s not placing the order. 😉

I wasn’t a fan of the feathered feet either. I kept hoping our ‘bonus chick’ from the hatchery would turn out to be a mop-topped Polish breed…not that I necessarily wanted a chicken with a silly hair-do, I just didn’t want to manage feather-footed birds. Now I can’t image not having Frodo here. He’s definitely becoming the new farm favorite! 😛

I have a friend that has the polish. He has to trim their “party hats” constantly so they can see.

Another fascinating history lesson.

Who knew there was so much history in chicken breeds? I sure didn’t. You should write a book or at least articles for magazines. I just love these posts and all I learn.

I never knew that poultry keeping had such a rich history like this. A fowl controversy indeed Clare!

I’m so happy to hear Frodo is approaching his reintroduction to the flock. Crossing my fingers for that to go well for all concerned!

This post amazed and amused me, Clare. At first I was thinking we humans are just so stuck on our petty disputes, and shaking my head — but then I thought about my grandfather, and how upset he would rightfully be if one of his clever farm inventions were stolen by a marketeer. So then, yes, I can understand why the controversy raged on. What I can’t understand is why these lovely, fine-tempered, and productive birds ever lost their popularity. They are beautiful even in black and white drawings. 🙂

I think a lot of the shifts in popularity for some of these breeds were perhaps more attributable to the new breeds, colors, and patterns of poultry competing in the marketplace. There definitely seemed to be a significant shift from purely practical and utilitarian fowl, to exhibition and commercially viable poultry in the mid-19th Century. Those that lay more eggs, or produce meat faster, were important even then. I actually find the advertisements in the old poultry journals to be very telling of the history of some of these breeds, more so even than the written articles themselves…especially the early ads for the White Leghorn, still our #1 commercial egg-laying breed.

That was so interesting! I really liked the part about The Colbert Bump, made me laugh out loud. Great analogy 😀

Wow, interesting! We have a grand total of 4 chickens, 2 of which are light Brahmas–they are sweet, and HUGE, and the poor things, while stars in cold weather, are not happy when it’s 103 here, hence my converting various containers into chicken wading pools. Seems to help a lot. They are dears, but I’m thinkin’ next time I’ll go for more lightly feathered creatures, for their sake.

Brahmas really don’t like heat at all. They’re often recommended against in southern climates. Even here, coastal central California, we can be prone in this valley to temperatures exceeding 100F in mid-summer. Frodo I know will hate the hot days. We have a lot of shady areas in the run and under the coop. If that’s not sufficient though, I can set up a mister in the chicken run just to help drop the ambient air temperature…although the last week, our fog-bank has been so thick, it’s been perfect weather for Frodo 🙂

Very interesting! Frodo is a distinguished bird, no doubt. His mysterious origins just add to his charm!

Once again, I am amazed at the history behind these birds, and your research. This really would make an interesting article, or perhaps a guest spot for you and Frodo on The Report!!!

Wow, what a great read! I adore the Brahmans, both light and dark. Frodo is a heartthrob to me, and those pesky pecking pullets better be nice to him!!! He’s the George Clooney of fowl… anyway well researched and written, both this piece and the previous, great job!!! I so admire your coop and fencing. Cheers! Bonnie

Frodo is such a handsome creature! Love that photo! Such pretty eyes!

Great post! Thank you for such interesting read!

An Indian breed that doesn’t like heat….? In-n-n-n-n-nteresting!

I love how you mix serious scholarship with humor in this article, and throughout your blog. Gotta love those steel engravings of chickens and Her Royal Highness.

I expect his ancestors, the original Shanghaes, were probably smaller birds, and much more heat tolerant. It’s clear that early American breeders were selecting for dense feathering, and large size. At one point, Brahma roosters would tip the scales at 14 lbs! Our modern Brahmas aren’t usually quite that large, usually between 10-12 lbs, but still sizable birds, with thick feathers, and definitely better suited to a cooler clime. Although, there are Brahma bantams that would probably do much better in warmer weather.

He is just beautiful!

Thank you for a very good post on the dark brahma. My pullet that is supposed to be a brahma doesn’t have the black and white that is typical of the breed. Instead, bella is all black with just a dot of white on her wing tips. Wonder if she’s really a brahma?

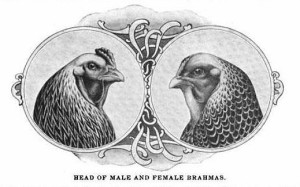

Brahma’s are slow to mature. The females don’t have as much white on their feathers as the males, it’s more subtle. The female Dark Brahmas have a silver-penciled plumage pattern. If she’s anything like our Partridge Plymouth Rocks, or Golden Laced Wyandottes, it takes quite a while for the intricate feather patterns to show in juvenile birds. Your girls are bit younger than ours, so I’d give Bella time to show her true colors 🙂