Last fall, and early winter, we experienced some significant rainfall events. One large storm after another sent water racing down our slopes, and off into the creeks. By December we were genuinely concerned that if that pattern persisted we’d slide into the creeks by February.

However, when the New Year arrived, it was as if someone flipped a switch. The clouds parted, and a cold, dry weather pattern set in.

It was only January though, and we still had plenty of opportunity to accumulate more rain before the end of our rainy season.

What we didn’t realize was that the significant wet weather was already behind us. We went from record rainfall in winter 2012, to a record dry weather pattern by spring 2013. In fact, January and February were the driest on record here. We knew that wouldn’t bode well for the gardens, or for wildfire season.

We’ve noted the results of the drought in the gardens, but we’ve also seen the drought’s effect in our apiary.

An early season check, in January, on feed levels in the hives, showed the colonies were robust, and building up quickly.

We’d had recent ample rain, and lots of gorgeous afternoon sun, providing plenty of perfect foraging weather for the bees.

As hive populations were soaring, by late winter we were concerned about repeating the previous season’s swarm-fest, so we decided that this season we were going to be more proactive about winter colony management.

We noted plenty of drones were present in the apiary by February, and elected to do some early season hive splits to reduce the likelihood of the colonies swarming in the spring.

We made a note for the next recheck to be prepared to take a spring honey harvest to prevent the colonies from becoming honey-bound.

The beautiful weather persisted, but as we slid from March into April it seemed less likely that we’d accrue any significant rainfall for the remainder of the season. Indeed, there was very little to speak of. The video below is what the farm should look like at some point between February and March, but this year we were dry.

By April, during a recheck of our hive splits, we marched out to the apiary with honey harvesting gear in tow. We expected, with all the glorious weather, that we’d be performing more hive splits, and taking honey. However, the colony build up had slowed, dramatically. There was no excess of honey, or population.

The previous year, by tax day, our apiary was throwing swarms left and right, despite spring splits. This is what healthy bee colonies do in the spring.

This spring there wasn’t a single swarm cell, or queen cup, in any of the hives. None. None of our colonies had any intention of swarming this year.

We are now squarely in the midst of a drought. In the garden some of the effects of this season’s drought have been expected, albeit relatively subtle.

The majority of plants here are endemic native plants, those plants aren’t irrigated, and our soils are relatively loose and sandy. In late winter we noted significantly fewer Calochortus, and Fernald’s Iris in bloom.

Then, most notably, the large stands of native deerweed (Lotus scoparius) on the slopes barely seemed to bloom at all.

The blooms that were produced didn’t persist for as long as normal here. I might not have noticed, except the advantage of maintaining a blog, a diary of sorts, is I have visual and written records from previous seasons to compare to.

The entire garden has seemingly been ahead by at least a few weeks all season. In some respects it hasn’t been bad. It’s a banner year for tomatoes, cucumbers, and peppers, although it’s been a challenge keeping the vegetable gardens sufficiently watered.

However, the effects on the native vegetation have been marked. It was obvious by the end of June that the dearth was already setting in.

Dearth (noun): a scarcity or lack of something. Origin: Middle English dearthe (shortage of food).

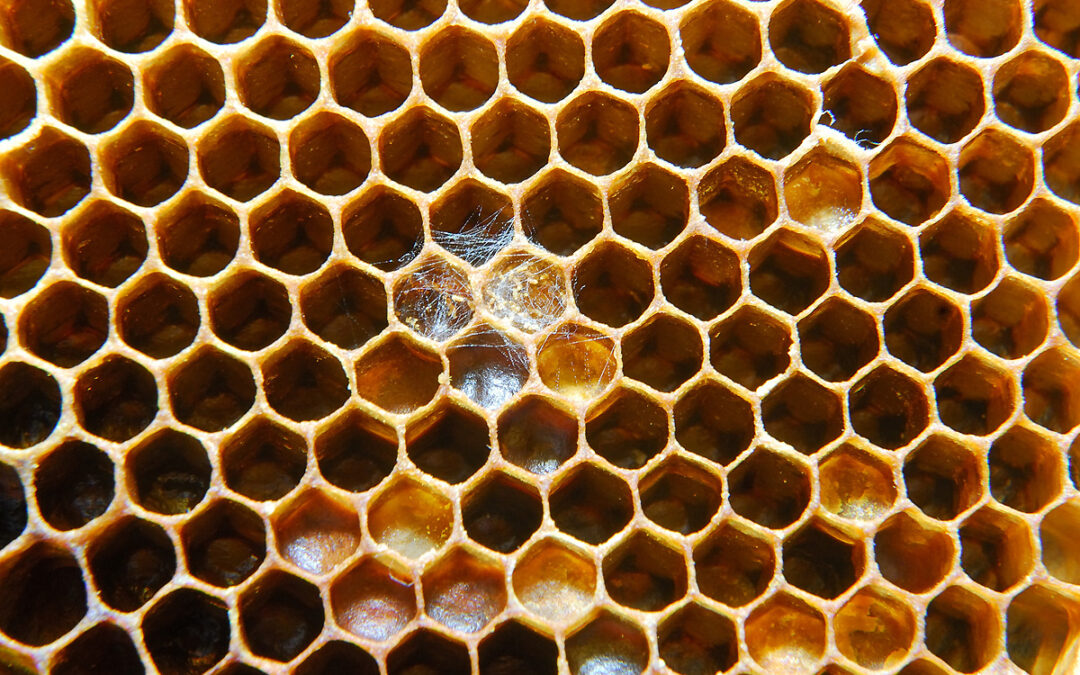

By mid-July in the apiary I noted hive entrance traffic was decreasing, and for one hive, the Rosemary colony, the drop in entrance population was precipitous. An inspection revealed that hive was empty, except for a few robbing bees exploiting stores. No bees, no dead bees or brood present, and no honey either. The Rosemary bees were gone.

The adjacent Lavender hive wasn’t looking particularly lively either.

Honey and nectar resources were low, at a time when we’d expect to be taking our last summer honey harvest. Consequently, the population in the hive was also low. There was worker brood present, but a notable absence of drone brood.

The Chamomile hive was a different story. A fairly robust colony, with decent honey reserves, and significantly higher population. For whatever reason, perhaps a stronger Queen, this colony was doing much better. However, despite the higher population, again no drone brood.

The Salvia colony had struggled continuously last year after it swarmed. Queen after queen failed. We know that colony went through at least four Queens last season. Thankfully, combining hives at the end of the season, with a colony we had split from that hive earlier that year, paid off. Salvia finally stabilized, and produced enough winter bees to make it through the winter months with flying colors. By mid-summer this year the Salvia colony was once again absolutely formidable!

All of the hives in our apiary are sourced from the same original feral bee colony (sadly, this robust feral colony, situated in our neighbor’s attic, finally died out this summer). Overall feral bees tend to produce very little honey, but instead, when the colonies are thriving, they do produce a LOT of bees. This colony was most definitely thriving. The advantage is they have more workers to task to foraging when resources are scarce.

However, they also have more bees to feed. We’ve never had a colony as aggressive as this hive, and I can honestly say that during that inspection I’ve never been happier to wear a full bee suit in 85 degree weather! Four boxes of brood and bees! A normal reaction to seeing that many bees in any hive would be to split it, and we would have, except for one small problem. No drones!

Of course, the advantage of no drones, meant no July drone trapping for Varroa mites.

We did consider removing brood from the Salvia hive, along with some extra nurse bees, and transferring them to the weaker Lavender hive, but by that point in the inspection the airspace in the apiary was nothing short of frenzied, and it was clear we were inciting a lot of robbing behavior. Even the yellow jackets were invading the airspace and attempting to gain entrance to the open hives.

The hives were closed up, and a month earlier than in years past, entrance reducers and robbing screens installed at the hive entrances. It seemed rather surreal to start managing our hives for fall robbing, in mid-July!

We did succeed in taking a very small honey harvest in July, but only from the two strongest hives, Salvia, and Chamomile.

In the meantime we’ve been feeding the Lavender colony in an attempt to help bolster the population. We’d prefer not to feed at all, both because we’re lazy busy, and because it’s not the best nutrition source for the bees. In fact, we haven’t fed any of our colonies in almost two years, but sometimes it becomes necessary. The challenge though was what to feed? The apiary is clearly heading into fall mode, with the absence of drones, but it’s still early in the season, and although winter bees are long-lived, encouraging the bees to produce them now really didn’t make sense. It seemed too early to start a fall feeding regime, even though by all accounts it looked more like fall in the apiary. Instead, we opted to summer feed, and help to make up for some of the lack of nectar producing plants in bloom.

For now we’ve been summer feeding, with 1:1 nectar, and pollen substitute. This stimulates the bees to think there’s more forage available, and encourages the queen to produce more brood. Of course, the problem is, there isn’t more food. One of our prime nectar sources here in the fall is Coyote Brush (Baccharis pilularis), but it’s blooming at least a month ahead of schedule.

This means that to support any increase in population, we’ll need to keep a close eye on the colonies through fall, and continue to feed as necessary. The question now though, is when to revert to fall feeding of 2:1 syrup. Usually we’d start that in late September, but with the gardens, and the apiary, running ahead of schedule this season, do we push that up?

Our next inspection we’ll be looking to see how well Lavender is recovering. Judging from entrance activity, all of the remaining hives are clearly contracting at the moment, although Lavender seems to be holding her own. However, over the next couple of weeks we’ll be striving to balance the population in the hives. Borrowing brood from the stronger colonies, to help bolster the weaker ones if necessary.

The risk of transferring brood in the late season is accidentally transferring a queen, so if we choose to do that, we’ll have to be especially careful, as any new replacement queens raised at the moment are unlikely to be well mated.

Population alone though won’t be our deciding factor. Queen strength will be. Despite feeding the Lavender hive, if that Queen still isn’t producing sufficient brood, and seems weak, to give the colony the best chance of survival it may be more prudent to combine Lavender with the Chamomile colony before winter.

This year has been a difficult one, both for the gardens, and for the bees in this area. As we’re already down one hive, with another teetering on the edge, we’ll be grateful if any of our colonies succeed in overwintering this year. I only hope that fall through spring will see the return of a more favorable weather pattern, so any surviving colonies can recover enough to be split by next February-March. For now, we’ll have to wait and see what the rest of this season brings.

So sorry to hear of your drought conditions. Hard to believe, but we are still suffering from our drought of 2011. Although we’ve had some rain this summer, the water table is low, and large trees are still dying. I never stopped to think about how terrible a drought would be to bees. I hope you can keep your hives thriving through the autumn and winter, and that next year’s rainfall returns to normal. Normal – wouldn’t that be fun?!

Normal would be fun, wouldn’t it? Quite honestly I’m not sure I remember what normal is around here. Sometimes I feel like Goldilocks. This summer is too hot, this summer is too cold. I think we’re due for a summer that’s ‘just right’! 😉

It seems we swing from extreme to extreme. We had an extreme drought last summer, and then an excessively wet spring this year. Things seemed to normalize in June and July, but then we had two weeks of “autumn” weather in early August with no rain, and now we’re back to high 80s and 90s, with no rain. It would be so wonderful to have a year with “normal” weather, but maybe that’s too much to hope for. I hope your bees come out of the drought OK, and that you get some “normal” weather, too.

We’re a little all over the place too. Spring like weather in winter, and winter-like cool temps (sans rain) in summer, then zipping back up into the 90s. I expect some temp fluctuations here because of the influence of the marine layer, but I moved to the coast side of the mountain as we’re supposed to get more rain. Someone didn’t get that memo this year though! 😉

It’s always very interesting to read all the details of your post. Before i get to the end, I always conclude that beekeeping is very difficult to manage, and i am glad i didn’t venture at all with it. But there is always a faint disappointment inside my head, because it really is very interesting. I just wonder whether those difficulties might me more in 4-season climate than our 2-seasons!

And i am sorry about your long drought, we had it this year, and then when the rainy season comes ‘when it rains it pours’ which resulted in a lot of problematic floods. Actually Metro Manila is still in it!

Beekeeping isn’t as easy as it used to be, that’s for certain. Between mites, and diseases that are more common now, it certainly is becoming more of a thinking person’s hobby.

I think there are challenges in any climate. We’re closer to a 2 season (wet or dry) climate here, than say someone in the Northeast, that has to contend with frigid cold winter weather. Sometimes our rains are unrelenting, trapping the bees indoors, unable to forage, other times, like now, there’s a lack of rain and nectar. Most of the weather here, overall, is very good, and I think it’s a benefit to our bees. This has just been an exceptionally dry year.

A few beekeepers get away with just putting bees in a box and walking away, but most don’t these days. There are so many things affecting bee health, and vigor, today. My neighbor kept bees years ago (before Varroa mites arrived), and even he’s astounded at everything bees have to contend with these days. With everything else going on, drought doesn’t help, but hopefully we can help them through this rough patch, and next spring will be more productive.

Maintaining the hives seems to be a lot of work. No drones a concern too I guess. I only see wild honeybees here, but would love to have a hive, but I would never have the time needed to take of it though. We have not had the rains either. When we did get one day of rain, it was damaging too.

If you’d like a hive in your gardens, but don’t have time to maintain one, you might contact a local beekeeper and see if you can host a hive. Many beekeepers look for places to host their hives. Too many bees in one location can be problematic, depending on what food resources are around, and some beekeepers are simply looking for variety in their honey, or need to move their hives for one reason or another. Some beekeepers will pay you to host, but I think most usually will just give you a cut of the honey. It can be especially helpful for you if you have fruit or vegetable crops that need pollinating too (although you do have to check local ordinances first in regards to number and location of hives).

It is always fascinating to follow Curbstone Valley! I am sorry to hear about the drought and its affect on the bees. I am glad you did get some good honey for all your efforts. I hope next year will be better, but farming and gardening on all levels is always a bit of a gamble, though we put our best expertise and our money and soul into it. Nevertheless, the rewards go beyond a particular harvest or seasonal result.

So true, it always is a gamble, and no two years are ever the same. There are always some successes, and some failures. That’s what keeps it all so interesting! 🙂

It’s always interesting to hear reports on your bees, Clare! It does seem as though we’ve had unusual weather, not normal and the way we expect! It does keep us talking… Our area is extremely dry and the fire season has been complicated by arsonists and dry lightning in the high country.

I’m glad some bee hives are doing well,…it would be very sad to not have honey. I so admire your beautiful and colorful hives.

We’ve had our fair share of arsonists running around too, as if fire season isn’t bad enough on its own this year! O.o

We are having similar problems over here, seasonal differences affecting the bees’ calendar I mean, not the drought. We had a very wet spring which was much longer than usual and we found that late spring and early summer flowers were blooming at the same time, so it’s been a story of famine and feast, really.

One thing that has been notable this year is that swarming season was put back by almost a month, very few swarming bees were out in April and May, but by July we had a local beek suffering from successive after-swarms for the whole month, they’ve only just settled down now but they were rampant for a while

We usually have a pollen/nectar ‘gap’ in June, but this didn’t materialise, however it’s looking like we may have this problem in Autumn if the Heather or Ivy bloom early

Things seem to have evened out here, and we’re hoping that the current forage will help them build up through Autumn for Winter, but it’s a bit like flying blind at the moment

This is definitely a year where being an urban bee, in an area with regularly watered gardens, is a huge advantage. With the climate shifting around, and native bloom cycles being delayed, or interrupted, it’s definitely more challenging for hives in rural areas. I was concerned about late season swarms this year, as they’re always a challenge to get through the winter months if you can recover them. However, our bees are so weak this summer they seem very resigned to staying put. I hope we see a little early season rain, and both our bees can find a little more forage before winter.

Sorry to hear about your bees. I have enjoyed reading about your bee experiences — and appreciated the knowledge you pass along. We hope to have a hive or two here in San Diego in the coming years. The city codes just changed to allow for bees on suburban properties, so we’re excited.

I wonder if we’ll have any similar problems to yours — or worse. We get next to no rain here in San Diego. Everything requires year-round irrigation.

That’s excellent news! I love that more cities are setting irrational fear aside, and encouraging beekeeping in the community.

Despite your lack of rain in that area, if you’re in, or close to, the city limit, where garden plants are irrigated, that can do a lot to mitigate the paucity of rain during the dry months.

When I talk to urban beekeepers here, many of them don’t understand why bees in an environment that comprises mostly California native forage, might struggle in the summer, as in the city, especially in a mild winter climate, bees can forage all year, and find plants in bloom every month. October to April here there’s usually plenty of food. Mid-summer, through September though, in a dry year, nectar sources can be quite sparse. Most native plants are dormant, and the landscape becomes quite dry and parched.

Looking forward to seeing you with some new hives next season! You’ll love beekeeping. It’s quite addictive! 🙂

I never realised that drought would have such an effect on the bees in rural communities. Hopefully there will be some late rains that will help with foraging and keep those wildfires from destroying more of the native flora.

The wildfire situation out here is alarming to say the least. The Rim Fire burning in Yosemite is staggering in its size, and terrifying in regards to its rate of spread. A true testament to how devoid of moisture the California landscape is this season.

Between unusual dry lightning storms in the last week, and crazed arsonists running around, I expect there’s more to come. Our peak wildfire season is late September to early October. I just hope that rain gives us a break and shows up early, and in earnest by then. We certainly need it, and bees would definitely benefit from a flush of late-season blooms too.

Droughts can surely screw everything up, never thought about them concerning bees before though. Definitely need a summer that is just right.

Honestly, I never gave a second thought to what drought does bees until I became a beekeeper. It always seems obvious how drought may affect wild mammal populations, either through poor survivorship of offspring, or individual losses due to lack of food. However, it really does affect the entire ecosystem when our weather conditions run to the extreme. Sometimes I think the ‘normal’ weather and seasons I remember are a romanticized figment of my imagination 😉

Clare, it’s always interesting reading when you tell us about your hives. In my wildest dreams I never would have thought so much work would be involved in keeping those little insects going. The amount of work you put in is admirable. Sorry to hear though that the season is such a dry one for you. We haven’t been that hot but it’s dry here as well. Predictions are for an early winter.

I’m often a little jealous talking to some of the old-timers that have kept bees for 30-40 years. They love to tell tales about catching swarms, throwing the bees in a box, and coming back to a harvest of 80-100 lbs of honey…PER HIVE! I just don’t see that happening among people keeping bees today (not unless they’re feeding their bees heavily, but we never take honey from hives we feed). It’s just intuitive watching the hives that bees, even healthy colonies, aren’t as robust as they should be. But, we do what we can, and hopefully things will improve, both weather wise, and with policy changes in regards to access to the myriad of pesticides these insects are bombarded with every day as they forage. In the meantime, I’m crossing my fingers for an early return to our wet weather pattern, and looking forward to lots of spring blooms next year!

Clare I had been wondering how the hives were doing. Sorry they are having a difficult time with the weather. Hoping things look up for the bees and they will produce more honey!!

I think this has been a difficult year for many critters, not just the bees. I was startled this morning by a rather emaciated looking doe and fawn. I’d left the door open to the building where we store bedding straw and hay, and the pair shot out of the door when I walked by. I almost had a heart attack! I found it interesting that they were willing to risk being in an enclosed space for the prospect of food. I wouldn’t be surprised if the wildlife here gets more bold as summer continues, between the lack of water, and food, available at the moment.